This post was originally submitted to Edutopia and is reprinted with their permission.

Mixed reactions to children’s e-books and the digitization of story time

Mixed reactions to children’s e-books and the digitization of story time

The news media and blogosphere were abuzz last month with the news that Apple is “reinventing the textbook” through the introduction of digital textbooks available for the iPad. With the announcement has come a myriad of opinions and speculations regarding the possible repercussions of Apple’s textbook reinvention for schools and for children’s learning.Many celebrate the availability of electronic textbooks for the classroom, surmising that their interactivity will make textbook content more engaging for students, their reduced cost compared to print textbooks will ease the financial burden on school budgets, and their format will literally lighten a student’s load and take less of a toll on the environment.Others, however, decry this move by Apple. They fear the possible end to traditional print books all-together, that too much control over our children’s education will be in the hands of Apple, that outfitting each student with an iPad and requisite IT support will create additional financial burdens on school budgets, and that existing access gaps may be widened when some schools cannot afford the technology.

The debate over what Apple’s electronic textbooks will mean for our formal education system comes at a time when we have not yet determined what tablet technology and the availability of electronic books (or “e-books”) can mean for children’s learning at home and other informal learning environments. Decades of research indicate a link between reading in the home and children’s literacy skill development. What is not yet known is whether that link may take a different shape depending on the medium of the books that are read.

Though e-books have been available for children to read on computers for some time, they are receiving quite a bit of attention recently due to the development of new, more mobile platforms on which to view them. Survey research from Pew Research Center indicates that the number of American adults who own a tablet or e-book reader nearly doubled this past holiday season, rising from an estimated 10% of the population in December to 19% in January. Still, parent reactions to children’s e-books, expressed through news media and blogs, seem to mirror the range of opinions regarding electronic textbooks: some parents love them while others adamantly keep their children away.

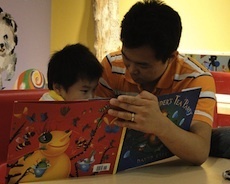

At the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, we are investigating how preschool-age (3-5) children and parents read e-books together and parental perceptions of e-books in their children’s literacy development. Our research consists of three separate but interrelated studies, all exploratory. Our first study was inspired by and modeled after research conducted by Julia Parish-Morris and her colleagues, who compared parent-child pairs read traditional print storybooks with pairs that read e-books on electronic console devices (i.e., Fisher Price). We conducted a similar comparison study, but observed our parent-child pairs as they read an e-book on an iPad as well as a print book. We observed their interactions with each other and with each book, and asked each party to describe their experiences and preferences.

Curious to learn more about the various considerations that may underlie families’ selection of books across platforms, we designed a second study in which we asked parents and their preschool-age children to select a print book or e-book to read together from an assortment of options. Again, we observed these pairs as they negotiated their book choices, and interviewed each party about the features and characteristics of the books that influenced their selections. Among the families we observed and interviewed, we found that book selection was understood as a valuable tool in developing specific interests and knowledge, especially science topics such as space, weather, or dinosaurs. In our sample, the interests cultivated among families tended to fall into three categories, which we have described as parent-driven interests, kid-driven interests, and parent-led interests. The two parent categories reflect varying intensities of involvement and collaboration with children in identifying and following interests through book selection, while kid-driven interests refer to topics that kids themselves identify as important, thus motivating reading on that topic. Each type of selection process represented a different entry point into co-reading and topic exploration for the families.

All of the insights and questions that have arisen from our first two e-book studies have led to the third branch of this research, which we are launching today. This study – an online survey for parents with children between the ages of 2 and 6 years – seeks to explore parents’ perceptions and use of e-books and traditional books with their young children.

If you are a parent of a 2- to -6-year-old and would like to participate in this survey, please visit the JGCC parent survey site. We would be thrilled to be able to incorporate insights gained from parents who follow our blog. Please feel free also to direct any other interested parents to our website to be included in our survey. Our goal is to include as many parents (and different perspectives) as possible!

We plan to close the survey later this Spring, and will write another post discussing our survey findings this Summer.Meanwhile, if you are interested in learning more about the Cooney Center’s e-book line of research, click here.