This past spring, Global Kids worked on a crowdsourced project to develop “Six Ways to Look at Badging Systems Designed for Learning,” a list of six different goals that badging systems are often designed to meet. During the summer, we beta-tested our own badging system within two of our programs to see in which of these six ways we could demonstrate positive growth.

This past spring, Global Kids worked on a crowdsourced project to develop “Six Ways to Look at Badging Systems Designed for Learning,” a list of six different goals that badging systems are often designed to meet. During the summer, we beta-tested our own badging system within two of our programs to see in which of these six ways we could demonstrate positive growth.

The first program was the Virtual Video Project, which focused on creating an animated film about climate change as part of Global Kids’ participation in the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development. The film was designed to raise awareness about real-life events that took place at the Rio+20 Conference and highlight what youth can do to live in a more sustainable world.

The second program, largely composed of youth from the first, was Race to the White House, in which youth used digital tools and games to learn about and educate others about issues pertaining to the Fall elections. In short, the youth created a game that allows players to “vote” on electoral issues that should receive attention in the 2012 Presidential campaigns: net neutrality, gun violence, medical marijuana, and college tuition.

Two of the six frames provided ample evidence to support the assertion that digital badges enhanced the youths’ learning.

1) Frame 1: Badges as Alternative Assessment

Badges can be a vehicle for providing evidence-based assessment and correcting key flaws in the formal K-12 learning environment through a model of alternative assessment. Global Kids, as an organization, rarely provides any systematic feedback to youth during their time in our programs (formative assessment) nor anything beyond a certificate at the end (summative assessment). Can the Global Kids Badging System provide feedback to youth both about their performance in our programs and about what they are learning?

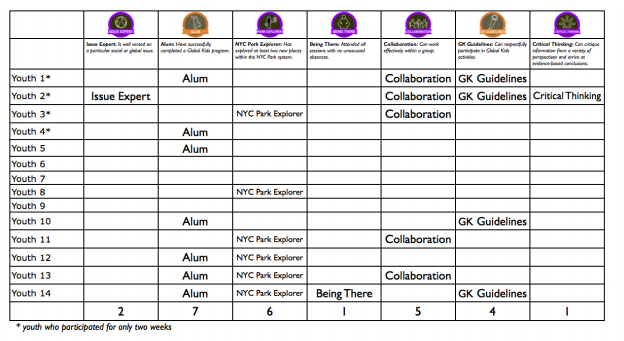

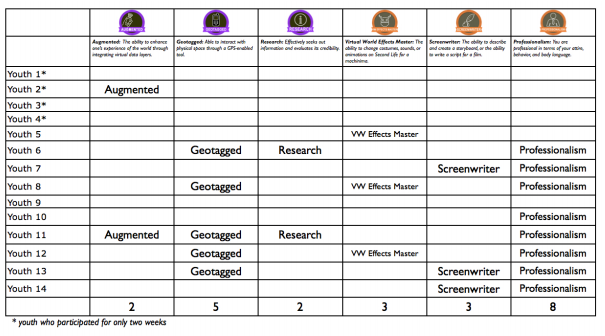

Global Kids youth leaders received confirmation 48 times that evidence submitted of their work met the requirements of one of 13 different educational objectives in their programs, averaging one badge per youth per week. At the same time, youth leaders received confirmation 10 times that their evidence did not meet the requirements. Both took extra time—for the youth to submit the evidence and the GK staff to review and evaluate—but the goal of providing formative assessment was significantly advanced.

In regards to feedback to staff about what individual youth were actually learning, the badge submission provided unparalleled information. Youth in Global Kids’ digital programs often blog about their experiences. Youth in these two summer programs were little different. As usual, the blog posts were brief, entertaining, and offered insight into the different ways the programs offered value and meaning to each youth. For example: “The first thing I wanted to do when I was done geocaching was go take a shower. You’re so sweaty and exhausted all you want to do is sit. One good tip is never sit or take a break while geocaching cause you will not want to get up lol.”

But the badge submissions were different. While the blog posts might have been in a response to an open-ended question (e.g. “What is something you liked about today’s program”), the badge submissions were in response to more specific prompts (e.g., “Demonstrate that you have developed or improved your abilities to work effectively within a group. You decide how you want to do that and share it below.”). Here is an example of one of the certified submissions:

Before this program, I never liked working in groups. I’d prefer to do work and/or projects on my own. However, preparing for this workshop, I got to contribute my ideas and opinions to the group I had to work with. If we came across a problem, we all pitched in an idea to a solution and overcame the problem.

GK Youth in the past have not had a vehicle, nor a reason, to provide us with such detailed information about their learning. All we might have observed, for this youth in particular, was that she was effectively collaborating with her group; not that the program provided her an opportunity to develop these skills nor that she had an awareness of her growth. Submissions like this provided us with information about both the youth and the educational impact of the programs.

2) Frame 2: Badges as Learning Scaffolding

Badges, as a form of scaffolded learning, can reveal multiple pathways that youth may follow and make visible the paths they eventually take. Scaffolding in a learning environment refers to providing guidance for youth to encounter learning opportunities that engage them at their level of ability before taking them to the next. In other words, badges are not used so much to assess or motivate, but to guide. Within an organization or program, that might mean using badges to provide youth a way to understand the options offered within a particular organization, customized to their current interests and abilities.

In our summer programs, we felt the time was too short to offer any significant scaffolding (beyond a special badge mentioned above for anyone who completed ALL of the other badges). However, we did hope that the wide range of badges would allow the youth to explore their own learning trajectories. We saw ample evidence to support that this was the case, even over such a short period of time. For example, while one youth achieved three of the four Soft Skill badges, most youth pursued none of them.

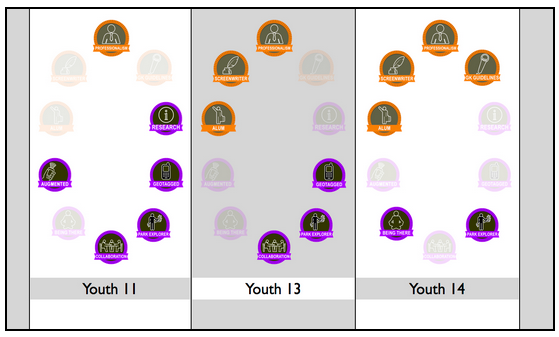

Of more interest, if we look at the individual constellations constructed by each youth—the group of badges they chose to pursue—we can see youth chose different paths through the system. Looking at just the three youth who earned the most badges (6), while they shared 10 badges amongst them, only two (Park Explorer and Professionalism) were shared by all:

Overall, the badges played a positive role in the development of our summer programs, engaged the youth, and offered them different learning pathways. It provided them with valuable opportunities to name, reflect upon, value, and share what they learned in the program; offered us unusually rich examples of their perceived learning; created a new and useful assessment relationship between us; and collected measurable data about their learning outcomes.

Global Kids looks forward to utilizing the lessons learned from the summer to continue to develop and hone the badging system over the coming year. (A full report on our experiences, from which this was excerpted, can be viewed here.)

Barry Joseph is the Associate Director For Digital Learning at the American Museum of Natural History. Located within the Education Department’s Youth Initiatives, Barry brings to the museum his dozen years working in youth development and nearly twenty years working in new media. His goal is to support the AMNH to advance its mission through the strategic application of digital media and learning pedagogy.

Daria Ng is Senior Program Associate at Global Kids, were she manages and implements programs that develop youth leadership skills and engages youth with global and social issues. She develops programs on social justice issues, human rights, global affairs, civic engagement, and environmental sustainability, often using digital media to bring forth the voices of youth.