This post was originally published in the Huffington Post as part of TED Weekends as part of the “Gaming for Life” series inspired by Jane McGonigal’s 2012 TEDTalk.

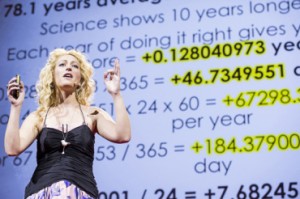

Jane McGonigal charged me up for more than the 7.5 minutes of life extension she promised. Yes, practicing her four “resiliencies” through gameplay may help make us happier and more productive, but, like her, my interests are in accelerating social change. So if her concussion inspired a game with the power to heal depression — let’s use these insights to make our schools “super better” through game-based learning (GBL).

Jane McGonigal charged me up for more than the 7.5 minutes of life extension she promised. Yes, practicing her four “resiliencies” through gameplay may help make us happier and more productive, but, like her, my interests are in accelerating social change. So if her concussion inspired a game with the power to heal depression — let’s use these insights to make our schools “super better” through game-based learning (GBL).

The timing might be right. The recent disappointing test results in states on Common Core-aligned exams have many educators and policymakers in a panic. Opponents of the Common Core, such as Diane Ravitch, are having a field day. President Obama is now focusing on the promise of edtech innovations like games to respond to concerns that schools won’t be able to meet new standards (see ConnectEd plan.)

The markets and kids themselves are responding. Right now, 97 percent of all youth say that they play video games. And there’s a surge in experimentation with GBL in education as a medium for engaging students in math, literacy, and STEM skills. Recent examples include new products like DreamBox and DragonBox. Initiatives to get kids to join the “maker movement” via game design competitions like the National STEM Video Game Challenge are hot!

But what do we know about the impact of GBL? Will effective practices scale? Is GBL a transformative way to deepen instruction and build new habits for life-long learning? Or will it go the way of many past reforms, with many practitioners taking “old wine” and placing it in “new bottles”?

The future of GBL is at a pivot point. Here’s my take:

The scientific research base is growing. The National Research Council’s important report on games and simulations for science learning (Honey & Hilton, 2011) found that simulations were a very effective tool in promoting academic knowledge and inquiry skills. The authors concluded that simulations and games have great potential to improve science learning in the classroom because they can “individualize learning to match the pace, interests, and capabilities of each student.” These findings echoed those from other researchers such as Mimi Ito that demonstrate games’ cultural appeal, and practical application to learning across settings.

A recent meta-analysis conducted by SRI International of over 60,000 games-related studies done between 2000 and 2012 found only 77 that undertook some experimental effort to formally test the effects on student academic outcomes. The report stresses the need for future studies to go beyond “simple questions about whether games are good or bad for learning” and argues that the efficacy of digital games for learning depends on design and implementation. We need to also–as Jane McGonigal argues–greatly expand our focus on key non-cognitive skills such as tenacity (mental resilience) and empathy (social resilience) which may mean more in helping children succeed now than ever before.

Educators seem ambivalent about GBL. Their uncertainty may have several roots including a still-emerging evidence base, tight budgets, and daunting accountability pressures. In a recent Cooney Center survey on teaching with games, we found that a large majority of educators report that games help students learn at a different rate and improve team skills. But the emphasis on assessments and standardized testing may be a considerable barrier. Games are not yet seen as vital to the educational bottom line. Cost is seen as a barrier to using digital games in the classroom and many educators report limited access to technology resources. We need to modernize our physical and human infrastructures to allow GBL to have a real shot.

The marketplace is digesting the GBL opportunity. Despite the success of some GBL products and services (such as Filament Games, MangaHigh and E-Line Media, the K-12 institutional marketplace is a notoriously tough nut to crack. Recall the edutainment fiasco of the 1990’s, (see “What in the World Happened to Carmen Sandiego,?“) The failure of educational software was not due to a lack of market demand for great products. (Products like Oregon Trail were immensely successful — 40 years later it has sold more than 65 million copies). Rather, market forces, such as the consolidation of publishers, and marketing and distribution strategies misfired and miscalculated consumer demand

As a recent report “Games for a Digital Age,” found barriers to GBL in education include:

–The dominance of a few big players and the prospect of future consolidation

–A long buying cycle, byzantine decision-making process, and narrow sales window

–Frequently changing government policies and cyclical district resource constraints that impact the availability of funding

–The demand for curriculum and standards alignment and research-based proof of effectiveness; and

–The requirement for locally delivered professional development.

To help overcome these barriers, the Cooney Center has convened the Games and Learning Publishing Council (GLPC). The GLPC is a multi-sector group with three main goals: to promote innovations that are ready for scaling within the GBL field, to develop and disseminate analytical tools, briefs and reports to help “raise the sector,” and to engage policymakers, developers and investors to deploy digital games to advance deep knowledge, and 21st century skills. This fall, the Council will roll-out surveys of educators uses of GBL, a series of videos focused on breakthrough professional development models, and the site gamesandlearning.org, that will assembles authoritative, highly accessible information for investors and developers.

Will games fulfill their promise in education, or join a litany of other solutions that peter out as “reforms du jour?” From my perch the growing research, practice and market interest demonstrates that GBL may be a surprisingly potent, low cost, scalable strategy. And, perhaps most importantly, our youth may benefit for a lifetime from the simple act of playing more!