Personally, I believe in general, when you look at the new assessments, you look at the new standards, you look at what employers want, you look at what people really need to thrive, they tend to align well with inquiry-based learning, blended learning. … But the fact is it’s really hard to design, develop, implement and support those types of learnings. I believe the people who can do that are going to experience enormous success.

– Alan Gershenfeld, president and CEO of E-Line Media

That’s a quote from “Turning Fantasy into Reality: Building Games that Schools Need,” a panel curated by the Cooney Center at the 11th Annual Games for Change Festival last month. It begged the question: are we (in the educational games community) living in a fantasy?

For example, it’s easy to imagine a utopian community where children explore rather than imitate, where teachers instigate rather than instruct, and where classrooms feel more like arcades or playgrounds. Outside of school, bus stops are equipped with games that help children learn the alphabet and hip hop laboratories materialize as quickly as fast food restaurants.

Is such a vision too far from reality to even be discussed? Because the reality is, as Alan Gershenfeld said, it’s hard to design, develop, implement and support that kind of thinking.

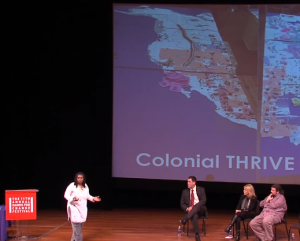

At the same event, the Cooney Center hosted a second panel called “Remaking Learning Live from Pittsburgh.” Standing under a giant projection of the words PITTSBURGH THRIVING, the four panelists took turns presenting their individual perspectives on the theme. Contrary to the lasting reputation it has as the abandoned home of the steel industry, Pittsburgh has rebuilt itself as a home for alternate learning. According to educator and researcher Michelle King, less than 20% of lifelong learning occurs within traditional learning spaces. “Learning can happen anywhere, anytime, anyplace,” said King. “How can I connect people to that?”

Source: still shot from video by GamesForChange

King has been an educator for 17 years, although she prefers to call herself a “learning instigator.” “I’m really trying to bring learning back as something sexy and exciting,” she said. Recently, she has been using digital media as a learning tool, and with astounding results. Working with a class of seventh graders, King and her co-teacher used Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel (a text that was once commonly assigned to first-year college students) to design a game about colonization. Colonial Thrive has gone through eight iterations since its first playtest and is now one of the great success stories from Pittsburgh’s Kids + Creativity Network, of which King is a member. But perhaps the most surprising fact in all this is that King wasn’t trained as a game design teacher: she teaches history.

“When you have five European nations and five Native American groups coming together in the New World, could they co-exist?” Colonial Thrive seeks to answer this question using a similar method adopted by Diamond in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book: drawing from multiple disciplines to find the answer. King’s students studied politics, economics, social systems, and even integrated math into the game, developing a new equation to measure a player’s happiness. “Not just playing the game but the design of the game is also a very powerful learning experience,” said King.

We can talk about a space where kids feel comfortable to learn and work and play, but have we actually built these communities for them? Michelle King seems to have hit upon something. She first got wind of the Kids + Creativity Network at its outset, during a chance meeting with Gregg Behr, executive director of the Grable Foundation. The two quickly recognized a shared passion in changing learning and formed an official partnership.

Behr just happened to be on the hunt for people like Michelle King. He knew that to make his ideal connected community of learners, he would have to search in different environments. “They’re gamers, they’re technologists, they’re roboticists, along with educators and librarians and museum exhibit directors,” said Behr, “people who are finding common ways to reinvent what learning looks like in a school, in a museum, in a library, in community centers, and elsewhere.” As for his own network, he has been able to bring together a thousand people from different disciplines to make a commitment to the Kids + Creativity Network. “They’re remaking learning for kids in the most extraordinary ways,” said Behr.

Of course such an ambitious project depends on support from the key institutions in the community as well. Kids + Creativity draws its funding and resources from an umbrella network of four organizations: the Allegheny Intermediate Unit, Carnegie-Mellon University, the Pittsburgh Technology Council, and The Sprout Fund.

These organizations first recognized Pittsburgh as a community that possessed a strong interest in education but perhaps needed support. “We realized as we gained momentum that we really needed some structure,” said Cathy Lewis Long, executive director of the Sprout Fund. And once they formed a structure, the opportunities for collaboration freely presented themselves. Many Pittsburgh students, for example, have now been part of a “playtest.”

“Creativity needs constraints,” said Drew Davidson, the director of the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon and a member of the Kids + Creativity Network. “If students show up and can do whatever they want, there’s not much that’s going to happen. But if you give them really well defined constraints, they’re going to hit up against those and then that’s where the creativity happens.” The Entertainment Technology Center believes innately that games can make a difference, and their hometown community of gamers interwoven with educators exists as proof.

But one thing game making and life changing have in common: they’re both hard. In particular, once you’ve identified your target, how do you begin to build? “It really started in an ad hoc, informal way,” said Cathy Lewis Long, referring to the Network. With the guidance of a few key organizations, a small-scale seed idea has grown to encompass a network of one thousand educators, innovators, and influencers who have transformed the community of Pittsburgh into a vibrant ecosystem of creativity. On any given day in Pittsburgh, a student has the opportunity to attend any number of public maker festivals, STEM workshops, events at libraries, YMCAs, theaters, and hip hop performances by fellow students.

Source: The Hive Pittsburgh

At the end of the panel, a positive example was made of the Elizabeth Forward School District, a half-industrial, half-rural community located in the Monongahela Valley south of Pittsburgh. “Certainly not a place where you would expect the future to be taking hold,” said Behr. The district had been performing poorly on tests, with a drop-out rate of 28 students a year. By chance, the district superintendent encountered some gamers from the Entertainment Technology Center, subsequently to be connected with the Kids + Creativity Network, and bravely allowed them to descend upon his district with new ideas. The result? The drop-out rate dropped to 1. Math scores went up 4%, reading scores went up 3%, and registration for summer programming rose by 500%. Elizabeth Forward is now one of 49 school districts in the nation-wide League of Innovative Schools ,and it exists as a testament to the power of connecting game designers who create the media with the educators who use it.

The panel made a positive example of Fred Rogers and his legacy. Behr went so far as to call his fellow panelists “three modern-day Fred Rogers.” Today, as our Executive Director Michael Levine closes out the Fred Rogers Center’s annual Fred Forward conference, we can doubly appreciate the work of Pittsburgh’s many devoted educators who carry that torch.