I spent last weekend on a camping trip with extended family. Having just completed a report on the use of digital games in the classroom, I was more than a little eager to consult with the kids in the group about their use of digital games inside and outside of the classroom. Given the popularity of Minecraft, I started there. “Do any of you guys play Minecraft?” I asked. Instantly there were three kids with three devices surrounding me, each showing me their “worlds.” They told me what they like about the game, and how they get tips and information about how to play. “Do you ever play Minecraft in school?” I asked next. Three confused expressions stared back. “We are allowed to use our phones and stuff for 30 minutes at lunch” the 12-year-old offered. I told him that some teachers use Minecraft in the classroom to teach different kinds of things and that they even make a special version of the game for kids to play in school. He looked at me like I had three heads and said “Weird. Is it any fun?!”

This recent example aside, the idea that games can be fun and educational is starting to take hold in the educational community. That these fun learning games can come in the form of games like Minecraft, rather than “skill and drill” games is icing on the cake for students and teachers. The number of recent popular press articles heralding a rising trend of digital game use in the classroom has made the team at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center wonder: just how common is this practice? And further, which teachers are choosing to use digital games in their teaching, what particular goals do they have for that game use, and what kinds of outcomes are they observing among their students?

With these questions in mind the Joan Ganz Cooney Center surveyed nearly 700 K-8 teachers about their use of digital games in their teaching (a follow-up to a similar survey we conducted in 2012 with BrainPop). I wanted to share a few of the highlights from our full set of findings.

About the sample of teachers

We recruited 694 K-8 teachers to participate in our online survey from survey company VeraQuest’s online panel of over 2 million members nationwide. In the first step we asked if panel members were employed as teachers; those that said yes were directed into the full survey. As such this sample comprises a large, fairly diverse group of teachers from across the country, though we cannot be sure our sample perfectly resembles a nationally representative sample.

Our full report is broken into four sections, focusing on (1) the “players” (basic analyses of who game-using teachers are), (2) the “practices” teachers engage in around game use with their students, (3) the “profiles” of teachers who use games with different frequencies and in different ways, and (4) the “perceptions” teachers have about digital game use barriers and opportunities for teaching. Below I highlight several from the “Players” and “Profiles” sections to contextualize and pique interest in our much more detailed full report.

The Players: Playing games at home predicts using games to teach

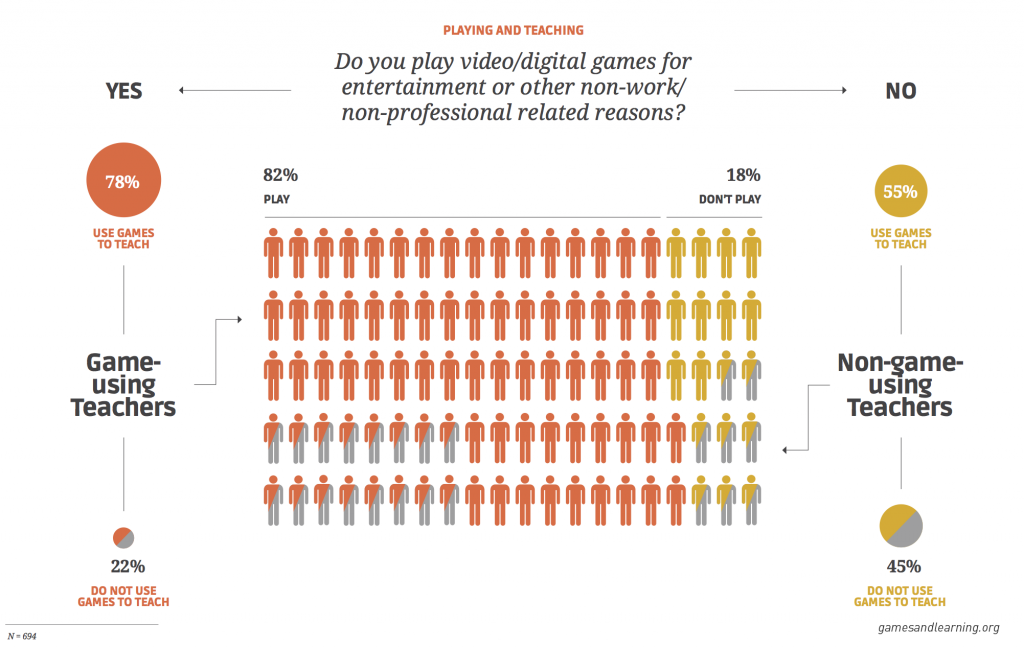

One aspect that sets our survey apart is that we asked teachers about their own personal digital game play–the extent to which they play games on their own time for fun. Next, we delved into the frequency and nature of digital game use in the classroom. With this information we are able to investigate the interplay between personal game play and game use in the classroom, yielding some intriguing insights. Among them is the finding that the majority of teachers do play digital games at least a little in their own free time (82% of our sample) and that personal game use is associated with game use in the classroom. As shown in Figure 1 above, teachers who do not play games themselves are fairly evenly split on whether they use them in their teaching. However, teachers that report playing digital games in their own time are much more likely to use them in their teaching than not.

The profiles: Four patterns of dispositional and support factors around game use

The profiles: Four patterns of dispositional and support factors around game use

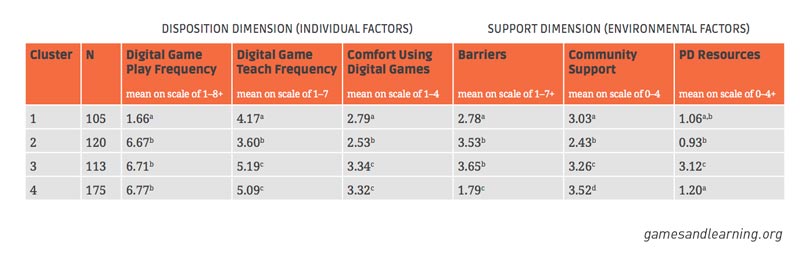

We weren’t satisfied to only compare teachers who use games in the classroom to those who do not, however. A prime goal of our study was to explore different patterns of game-use in the classroom, including both the frequency and nature of digital game use in teaching. For this we used cluster analysis, a statistical method for identifying natural groupings of people within a data set who vary along a set of variables. A cluster of teachers exhibit characteristics that are similar to each other and dissimilar from those in other clusters (we refer to these clusters as “profiles” of game-using teachers).

Cells within a given column that have different superscripts indicate statistically significant differences in cluster means for that variable (e.g., cluster means that carry an “a” superscript are significantly different from those with a “b,” but not from each other).

To identify possible profiles we compared teachers along two dimensions. The first dimension comprised individual disposition factors, including personal game play frequency, frequency of game use in the classroom, and comfort level using games in teaching. The second dimension consisted of environmental support factors in the school, including barriers to digital game use support from administrators, colleagues, and parents, and the number of professional development resources they use to learn about digital game use in their teaching. Our analyses indicated that there were four different profiles of teachers who differed from each other along these dimensions. The groups’ respective characteristics on each of the six variables are portrayed in Table 1, and each teacher profile is explained in greater detail below.

We named the first group of teachers that emerged from the cluster analysis the Dabblers, since teachers in this profile played games on their own and used games in the classroom a low or moderate amount, and reported fairly low comfort using games to teach compared to other game-using teachers. In addition, Dabblers reported a moderate number of barriers to game-use, such as insufficient time or a lack of technology resources, moderate support of game-use from parents, colleagues, and administrators, and only a few sources of professional development around game use in teaching. These teachers, representing 21% of our sample of game-using teachers, “dabble” in game use in their teaching but do not seem to be driven or able to use games a lot.

We named the first group of teachers that emerged from the cluster analysis the Dabblers, since teachers in this profile played games on their own and used games in the classroom a low or moderate amount, and reported fairly low comfort using games to teach compared to other game-using teachers. In addition, Dabblers reported a moderate number of barriers to game-use, such as insufficient time or a lack of technology resources, moderate support of game-use from parents, colleagues, and administrators, and only a few sources of professional development around game use in teaching. These teachers, representing 21% of our sample of game-using teachers, “dabble” in game use in their teaching but do not seem to be driven or able to use games a lot.

The second group of teachers, which we dubbed the Players, reflected unexpected characteristics as they played games on their own a lot but used them in their teaching quite rarely. The efforts of these gamers to use digital games in the classroom may be subverted by the fairly high number of barriers they face, low support from parents, colleagues, and administrators, and their lack of access to professional development resources. This intriguing profile comprised 23% of our full sample of game-using teachers.

The second group of teachers, which we dubbed the Players, reflected unexpected characteristics as they played games on their own a lot but used them in their teaching quite rarely. The efforts of these gamers to use digital games in the classroom may be subverted by the fairly high number of barriers they face, low support from parents, colleagues, and administrators, and their lack of access to professional development resources. This intriguing profile comprised 23% of our full sample of game-using teachers.

We named the next group to emerge the Barrier Busters as these teachers use games frequently in their teaching, despite the relatively high number of barriers to game use they report. These teachers, who also report fairly high personal game play, are also aided by their relatively strong support of game play from colleagues, parents, and administrators and higher number of sources for professional development around game use in teaching compared to teachers in the other profiles. These teachers, who seem to break through the barriers to in-school game-use they face, make up 22% of sample of teachers who use digital games in the classroom

We named the next group to emerge the Barrier Busters as these teachers use games frequently in their teaching, despite the relatively high number of barriers to game use they report. These teachers, who also report fairly high personal game play, are also aided by their relatively strong support of game play from colleagues, parents, and administrators and higher number of sources for professional development around game use in teaching compared to teachers in the other profiles. These teachers, who seem to break through the barriers to in-school game-use they face, make up 22% of sample of teachers who use digital games in the classroom

The final profile, 34% of teachers who use games in the classroom—we named the Naturals. Perhaps their frequent use of digital games in the classroom come naturally to them as they are playing games a lot on their own and they report being quite comfortable using games to teach. It may also be natural to them to use games to teach as they face the lowest number of barriers and report the highest levels of support from other teachers, parents, and school administrators.

The final profile, 34% of teachers who use games in the classroom—we named the Naturals. Perhaps their frequent use of digital games in the classroom come naturally to them as they are playing games a lot on their own and they report being quite comfortable using games to teach. It may also be natural to them to use games to teach as they face the lowest number of barriers and report the highest levels of support from other teachers, parents, and school administrators.

How might these profiles be useful?

As we continue to learn that digital games can be educational and fun and what features and implementation strategies influence both learning and enjoyment, a parallel line of research should examine what kinds of information about digital game use should be communicated and to whom. To that end, we think that these and other profiles of game-using teachers can be leveraged to understand which teachers are using digital games to teach and how patterns in their perspectives, behavior, and support may underlie the nature and efficacy of game-use in teaching. For example, if “Players” have the gaming expertise, interest, and comfort level to effectively incorporate digital games in their teaching, perhaps the administrators and parents they work with should be given more information about the benefits of playing high-quality digital games in the classroom to lessen the barriers that “Players” face.

We encourage you to visit the full report, which Lori Takeuchi and I produced together, and learn about the other ways we use the teacher profiles to understand how to better support teaching in game-based instruction. As always, our hope is that this work will foster fruitful dialogue and follow-up research, and we welcome your comments, questions, and suggestions!