A few weeks ago, the Cooney Center released Family Time with Apps, which helps parents think carefully about how (if at all) they want to support their children’s app use. A central theme of that guide is “joint media engagement”: the entire family benefits when parents and children explore the app landscape together. Even the guide itself is designed to be explored by the whole family!

When I talk to parents about supporting their children’s learning, I frequently stress how powerful this co-engagement is. Technology is cool, but parents are a child’s first and most important teachers. So in our preschool app series Leo’s Pad, we’ve specifically designed some games to be co-played by a parent and child. And when my own preschoolers are on the tablet, I try to be right there with them, helping them to reflect on and learn from their digital experiences.

But I can’t always be there, and neither can most other parents and grandparents. There are times when our children will engage with digital technology while we’re making dinner, driving the car, traveling for work, etc. And, of course, there may be times when it’s better for a child (especially an older child) to overcome some digital challenges entirely on his or her own. How can we support our young children’s in-app learning when we’re not there to observe that learning?

At Kidaptive, we’ve spent the past two years building one answer to that question. A few weeks ago we released Learner Mosaic, a free iPhone app that uses preschoolers’ in-app learning to provide their parents with personalized, research-based tips and activity suggestions. I’m hopeful that some of the principles we followed in developing our product might be helpful for other educators and app developers as well.

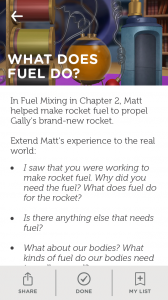

Perhaps the best way to explain what Learner Mosaic does is by example. Let’s imagine that one evening, my son (whom I’ll call Matt for this example) spends 20 minutes engaging with Leo’s Pad. During that time, he plays a game in which he gets to mix rocket fuel with budding astronomer Gally (Galileo) and child scientist Marie (Curie). Learner Mosaic can support this learning in three ways:

- Support co-play: If I happen to be around, I can read suggestions for how to play the fuel-mixing game alongside my son.

Screenshot from Learner Mosaic - Connect in-app learning to the real world: If I’m not there when my son plays, I can read a “conversation starter” the next morning encouraging me to connect his in-app learning to the real world by talking to him about fuel.

- Offer related real-world activities: And finally, if my son struggled to follow the multi-step instructions in the game, Learner Mosaic might offer me a simple instruction-following game to play with my son that weekend involving a sequence of silly movements.

We chose these three ways of supporting in-app learning based on research in the fields of digital media and learning, cognitive development, and good ol’ educational psychology. We want to help parents engage at whatever times and in whatever ways work for their family. And if parents aren’t around as their children engage with apps, Learner Mosaic can still (a) show what their children have been doing and learning and (b) offer ways to extend that learning into the real world through conversation and play.

Another way we’ve tried to give parents something that works for their family is by personalizing all of our recommendations. Our psychometric engine assesses each child’s progress in over 75 early-learning skill areas, using both the child’s digital gameplay and the parent’s responses to simple questions that we ask in Learner Mosaic. We also ask the parents which areas they’d like to focus on with their children. Our system then selects the best recommendations for that parent based on the child’s progress, the parent’s preferred focus areas, and the child’s recent activity (both online and offline).

And where do these recommendations come from? Our team of developmental psychologists, learning scientists, psychometricians, preschool teachers, and parents wrote every one of them. The vast majority are drawn from peer-reviewed research, but some also come from team members’ years of professional practice in preschool classrooms.

We are proud of Learner Mosaic, but it is only one small part of an ecosystem that includes many great ways for parents to support their early learners. More important are the principles behind the app:

- Base recommendations on good child-development research

- Personalize support with both valid assessments and knowledge of specific audience

- Connect in-app learning to real-world contexts

- Support transfer of skills from digital to physical contexts

The first two principles are about us as parents. We all want to do the best we can for our children, but we are incredibly busy. We don’t have time to wade through either the research literature or the ocean of general how-to blogs/newsletters/etc. What we crave is something that is (a) authoritative and (b) specific to our family’s needs.

The second two principles are about our children. The holy grail of learning is transfer: the ability to adapt something learned in one context to apply it in another. When people ask whether children playing digital games are “learning anything,” for instance, what they mean is “learning anything that is useful outside the game.” Helping learners understand how what they’ve learned in context A relates to context B can greatly improve transfer, as can giving them different opportunities to apply specific skills and knowledge.

The more our community of educators, researchers, app developers, and advocates embraces these principles, the better off our 21st-century children will be!

Dylan Arena is a father of two children under the age of six. He’s

Dylan Arena is a father of two children under the age of six. He’s

also co-founder and Chief Learning Scientist at Kidaptive, which

creates personalized learning experiences for children and parents to

improve educational outcomes. Dylan spent eleven years at Stanford

studying cognitive science, game-based learning, and next-generation

assessment while earning a bachelor’s degree in Symbolic Systems, a

master’s degree in Philosophy, a master’s degree in Statistics, and a

Ph.D. in Learning Sciences and Technology Design. He has been a

MacArthur Emerging Scholar in Digital Media and Learning, a Gordon

Commission Science and Technology Fellow, a Stanford Graduate Fellow in Science and Engineering, a Gerald J. Lieberman Fellow, a FrameWorks Fellow, and a United States Presidential Scholar.