This post was originally published on gamesandlearning.org.

Whether developing formal learning games aimed for the classroom or apps you want parents to purchase for their kids, the role of research in game development and assessment of learning is one of the most critical decisions developers must make.

A discussion at this week’s SXSW Interactive encouraged developers to consider the way they use product research and how best to guard against the pitfalls of group-think.

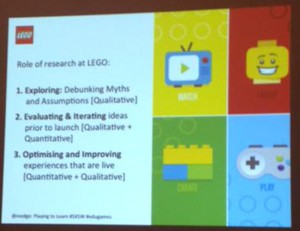

For game giant LEGO research counters two major challenges, said Cecilia Weckström, senior director of LEGO.com – battling over-confidence and keeping in mind their audience.

“It takes a lot of effort to step out of where we are now and remember what it was like when I was five. So being aware of that and trying to set your work up in such a way to try and see the world through the eyes of a child is critical,” she told the audience, adding that if you don’t change your perspective, you run the risk of simply saying “this would be fun. I’d like to do it.”

She pointed to the experience of her own company, where she said two decades of strong sales had created a problem, leading “to a culture where we all thought we knew what it took to make great products.”

The company went through a period where sales grew stagnant and LEGO had to reinvent itself and launch new products. Weckström said the time had been a challenge, but also taught her that:

Just at the time you think you have it just right, that’s the time to start questioning it all over again because success is the biggest thing that can get in your way and will keep you from seeing the other gorilla in the room until it is too late.

–Cecilia Weckström, senior director of LEGO.com

But oftentimes the role of research is more clear-cut, said Tinsley Galyean, whose Global Literacy Project has been putting apps and tablets in some of the most remote locations on the globe to see how these tools could improve reading.

Galyean said good research plans aim to answer critical questions like, “Is it usable? Is it engaging? And, third, does learning actually happen when kids engage it?”

But that is not to say that the researcher’s work always resonates with creative team.

Elliot Hedman, whose research into human behavior and emotions has broken new ground, recalled how at one point he had been working with kids to understand why they didn’t want to play board games. He said his research found it had a lot to do with reading the directions. Hedman said he remembered, “one kid told me, ‘It’s like going to school.’”

He took the research back to the team and they responded by saying there wasn’t enough time to fix it. It left him realizing that, “As a researcher 10 percent of your work is identifying the problem and at least 50 percent of your work is helping others understand the problem and creating a joint solution to address the problem.”

Structuring Effective Research

Still the panel stressed much of the challenge of getting the most out of research has to do with communications and clarity.

Weckström said much of this has to do with encouraging both an “open road” approach to designing where everything is on the table and creativity flows and a more “closed” process where the best solution is tested and accepted.

She said at LEGO the design process starts with more of the open road where many ideas and solutions are proposed and toyed with, but then, she added, “you start to want to evaluate and determine what is the best solution and so you move into a closed environment,” which is much more organized and rational. She stressed that developers should ensure that the entire team is in sync when doing both forms of research to ensure a clear process.

Galyean compared the LEGO process to the Global Literacy Project’s effort by saying in his shop they have different skillsets in the design effort, including designers, coders and researchers and each creates a constraint on the free flow of ideas.

But that’s a good thing, he added.

“You learn quickly it sucks not having constraints,” he said, adding the constraints “create the puzzle or problem you are trying to resolve.”

But well constructed research can work with those restraints and deal with other challenges if they are factored into the design and research process, the panel said.

The key, Hedman said, is to realize the limitations and incorporate them.

He said that research involving kids will always be a challenge and told the story of some of his research he had done for Weckström’s LEGO. A young boy had become frustrated trying to play with the LEGOs and went to his mother and begged to play with something else. When Hedman asked what the boy enjoyed most, he thought for a moment and said, “I really loved the LEGOs.”

The moment made Hedman realize, “When you interview kids they often don’t want to tell you how they are feeling want to tell you how they think.”

The panel was moderated by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center’s Michelle Miller. The Center is also responsible for gamesandlearning.org.