Today, the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and New America are releasing a report of our recent market scan and content analysis of language- and literacy-focused apps for young children. The report, Getting a Read on the App Stores, presents our key findings regarding the characteristics in the apps’ in-store descriptions as well as various features within their actual content.

Today, the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and New America are releasing a report of our recent market scan and content analysis of language- and literacy-focused apps for young children. The report, Getting a Read on the App Stores, presents our key findings regarding the characteristics in the apps’ in-store descriptions as well as various features within their actual content.

On a personal level, the release of this report is also a poignant milestone. I have been conducting research on various intersections of youth, families, and media for nearly ten years now, yet this study is of particular importance to me. Just this August, in the course of leading this research, I became a parent. With the birth of my first child I gained a critical new stake in the very subject I was investigating: the availability, promotion, and features of apps marketed as “educational” for children birth through age 8.

During a recent airplane trip I discovered that my 4-month-old daughter, Claire, is already entertained and even soothed by my iPhone. To my relief (and that of my fellow passengers) she immediately quieted down as she gazed at the photos in my phone’s gallery (which, of course, were mostly of her). But my relief was mixed with some apprehension. Claire will grow up with screens all around her. Increasingly, they will be part of her daily life, even part of her education. Did I really want to introduce them into her world so soon? How would I determine the optimal “media diet” for her—finding the best products and balancing the appropriate time and contexts of her screen media use with her constant desire to use them?

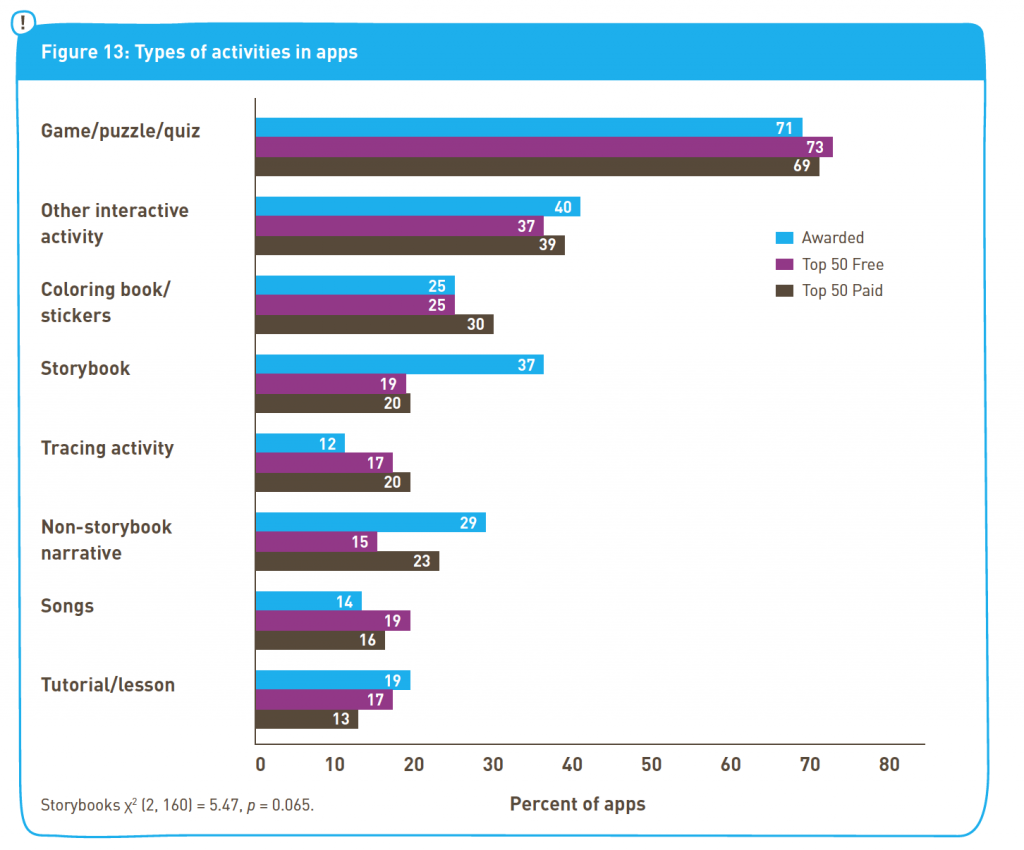

As a parent reviewing the findings from our app scan I have similarly mixed feelings. On one hand, there is cause to be optimistic. We encountered no shortage of language- and literacy-focused mobile apps for young children. They are among the top promoted apps in app stores: in our study they comprised 34% of all Top 50 Paid educational apps and 29% of Top 50 Free educational apps across popular app stores (Apple’s App Store, Amazon, and GooglePlay). Many are also given high marks by expert review sites like Common Sense Media, Parent’s Choice, and Children’s Technology Review. In the aggregate, young children’s language and literacy apps incorporate diverse activities (see figure below) and innovative features like the ability for children to integrate their own voices and images within the app.

And yet the task facing parents and educators searching for high quality language and literacy apps is a daunting one. App stores lack policies that could structure the information given in app descriptions or set standards for content or development characteristics necessary for apps to be classified as “educational.” What has resulted from the lack of such policies is the substantial variability we encountered in our study—variability in the information consumers are given about apps before deciding whether or not to purchase them, as well as in the information and features present in the apps themselves. In fact, the sheer amount of information in descriptions reflected a wide range; the length of descriptions in our sample varied from 13 to over 1,000 words. Key pieces of information that could guide consumers’ decision-making were spotty as well. Nearly 40% of the app descriptions we looked at did not give a target age-range or developmental stage of the children for whom the content was appropriate, using terms like “for kids” instead. As shown in the figure below, relatively few descriptions mentioned an underlying educational curriculum, one of the benchmarks of educational quality we looked for in our sample.

These examples illustrate a compelling overarching message from our findings: as consumers, the onus is on us to do our homework when searching for high quality language and literacy apps for our children. They are out there. What are lacking are guideposts to direct us towards them and away from those lacking educational value. As such, our team arrived at several suggested strategies to offer parents and educators who are searching for language- and literacy-focused mobile apps for young children:

- Search for information about apps through different means and sources. Our findings showed an interesting pattern: consumers will find different apps depending on where they search for them. Those that we found among the Top 50 educational lists in app stores were largely not the same apps given accolades by expert review sites. Furthermore, we found different types of parent-directed information and app content features among the apps based on whether they were Top 50 Paid, Top 50 Free, or expert-awarded apps. We encourage consumers to cross-reference apps of interest across different app stores and review sites, and to also look for greater detail within associated producer websites.

- Give voice to frustrations and great finds. We found that websites associated with apps as well as the apps themselves often contained email links to contact the developers (“contact us” links). In order to effect change in the marketplace or reinforce desirable attributes, parents and educators should make use of these opportunities to send their feedback. Developers want to sell their apps, and user feedback would be a useful tool for helping them ensure that their offerings reflect market demands. We should also voice stipulations that the app stores we patronize better serve our needs. If we do not demand standards-based categorization of children’s apps or more (and more consistent) information about them then we will be stuck with the status quo.

As we prepare to release Getting a Read on the App Stores this week, I do so as both an inspired researcher and a concerned parent. As a researcher, I am intrigued by the gaps in our collective understanding that the report has surfaced. Already, our team at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and New America is planning new investigations of the attributes within children’s educational apps and the guidance surrounding their use in order to fill these gaps for developers and consumers. As a parent, I am approaching this work with added urgency. After all, it’s up to me to locate the best apps for Claire.