Last week we released Getting a Read on the App Stores by Sarah Vaala, Anna Ly, and Michael Levine. Here, Anna provides some tips for developers who are creating literacy apps for young children from an industry perspective.

Ever since Apple’s App Store launched in 2008, business analysts, developers, and designers have been trying to figure out how to get their app to the top through bursts of marketing, thoughtful design, or carefully crafting keywords. As more apps get uploaded to the store, the competition becomes more fierce. No one knows for certain how the algorithms work for each of the app stores though some app marketing firms speculate that factors like the number of downloads, ratings, and engagement may be taken into account. It gets even more complicated as search algorithms are changed from time to time. The most recent one that we are aware of seems to have improved the results that are returned when searching for apps, surfacing more relevant results and competing apps. This is good news for developers who may see their product jump to the top of a search results page. And for users, especially parents, this could potentially help them better sort through the thousands and thousands of apps for their children.

In general, information about the algorithms, download trends, user habits and preferences, and other analytics could potentially be gold for developers, helping them better design and market their apps to reach their target audience. And hopefully, that information could help bring to light better learning apps to the families hard at work trying to discover them. Companies like App Annie and Fiksu offer services to developers that help them sort through all that data.

To help parents, designers, and developers, the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and New America Foundation have produced Getting a Read on the App Stores, a scan of the top literacy apps for children in the Apple App Store, Google Play, and Amazon Appstore. Though a sliver of the giant realm of apps, we found that literacy apps for young children made up a good chunk of apps in the education categories of the stores. The goal of the study was to put ourselves in the shoes of the parents. If we were parents trying to find apps that could help our kids learn to read, what would we find? What would be at the top of the heap? What would we find if we tried going to sites that apparently guide our choices? And once we downloaded the apps, what would our kids encounter? These were just a few of the questions we sought to answer during our study.

After the months-long scan, we discovered that there was a dearth of certain qualities in children’s literacy apps that made it into our sample, which was made up of titles on the Top 50 Free and Top 50 Paid Education category apps of the Apple App Store, Google Play, and Amazon Appstore, and Expert Awarded Apps from Common Sense Media, Parent Choice Awards, and Children’s Technology Review. We highlight these qualities in case folks want to figure out how they could potentially stand out from the crowd. However, note that this doesn’t necessarily mean that this could lead to leaping past other apps to the top. There are a multitude of factors that impact that journey, and this may be one of them. And some of these rare qualities also stand out because research claims that they increase learning and engagement. Take a look at a few of these uncommon features that might make your app stand out from the crowd.

Joint Media Engagement

Few apps in our sample had explicit functions within the apps that allowed for joint media engagement. Only a handful of apps allowed children to share content, connect socially through the app, or co-use it with others like their caregivers. Specifically just two had functions such as collaborative or competitive play with another player and 10% allowed users to contact or share content with others either through e-mail, text, or in the app. This is especially intriguing because researchers have found that connecting with others through media and using media together could help deepen children’s learning.

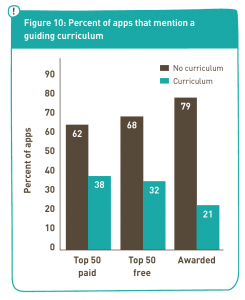

Benchmarks of Educational Quality

Benchmarks of Educational Quality

Research indicates that qualities like relevant expertise on the development team, an underlying curriculum guiding content development, and research testing of the program’s usability and efficacy reflect deliberate development decisions that tend to boost the chance that children will learn the intended content (Anderson et al., 2001; Fisch & Truglio, 2000a). However, fewer than half of the apps in the sample provided information about their development teams in general and fewer than a third claimed to have an underlying educational curriculum. As for testing, only 24% of the apps stated they conducted tested and most of the testing was just usability testing vs. learning efficacy.

In-App Information for Parents

Considering that joint-media engagement is a positive factor in increasing learning and that parents have difficulty finding the best apps out there, it probably doesn’t hurt to have information for grown-ups on how the app could be educational and helpful for their children as well as how they could engage with their kids around the app content. Yet, a minority provided feedback about children’s performance (17%), gave suggestions on how to enrich the app’s use (17%), or offered details about educational content (14%).

Certain Age Ranges

The number of apps targeted to kids 6-8 years old took up only 5% of the sample compared to 0-5 years old (17%), and a whopping 39% specified no age range. Caregivers who are trying to find something for their child within those age ranges will have to look hard. Given that an NPD study (2012) on parental behavior around app purchases found that three-quarters of parents with kids ages 2 to 5 look for age-appropriate apps when putting in search terms, specifying such details in the app could be key to getting discovered.

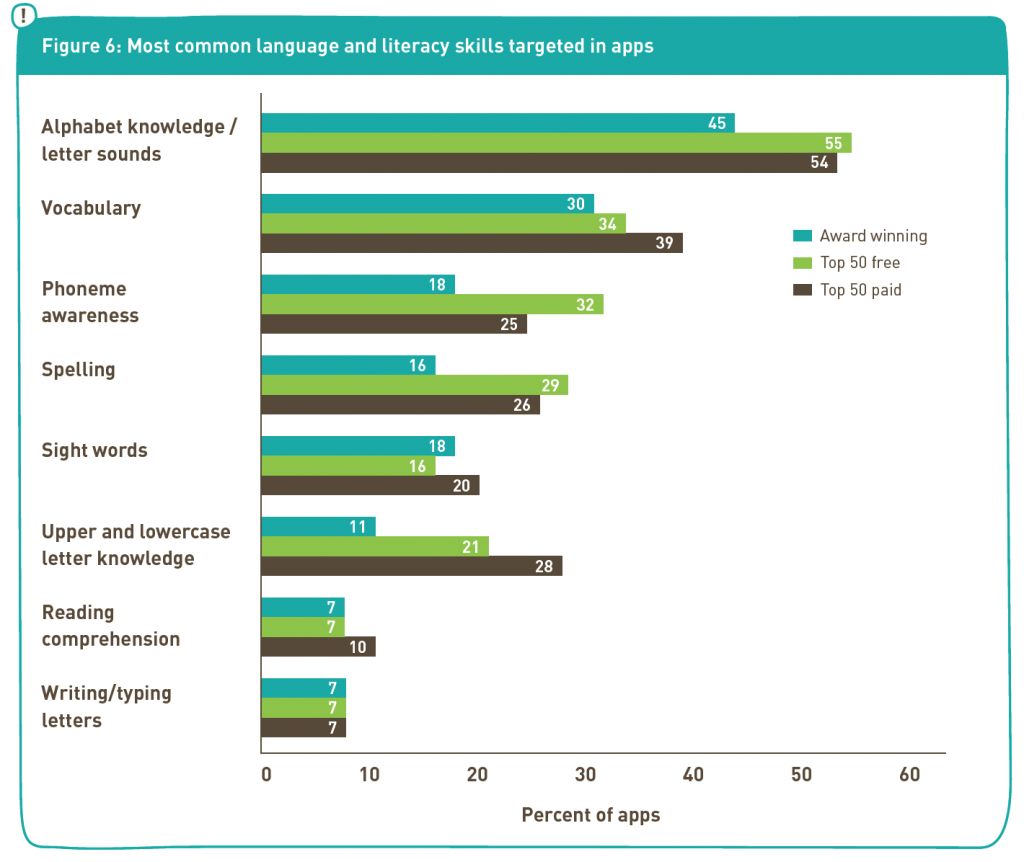

Advanced Language and Literacy Skills

To become a better reader, a child must learn a number of different skills of varying complexity between birth and age eight. These range from producing basic sounds to reading fluently and comprehending what is being read. However, we found that not many apps in our sample targeted advanced language and literacy skills like writing and typing letters, reading comprehension, upper and lowercase letter knowledge, or sight words. Parents will be hard at work when searching for apps beyond the basic building blocks such as ABCs and sounds that letters make. They might have to look elsewhere to figure out how to teach the higher order skills like storytelling or self-expression.

Storybooks, Tracing, Non-storybook Narrative, and Songs

When we dug into specific activities within the apps, we found that the apps that had won awards from expert review sites like Common Sense Media and Children’s Tech Review were more likely than other apps to have storybooks or other narrative formats (56%, compared to 39% of Top 50 Paid and 29% of Top 50 Free). Tracing and songs were also not as frequently found in the apps vs. games, puzzles, and quizzes. Having more narrative doesn’t necessarily lead to better educational outcomes. According to “A Capacity Model of Children’s Comprehension” (2010), Fisch theorizes that when the narrative content is deeply entwined with the educational content, it could lead to deeper comprehension of the educational content. However, if the educational content is tangential to the story, learning may suffer.

Special Features like Recording, Photos, Looping, Translation, Dictionaries and Printing

Of the many features we looked for within the apps, recording, taking and storing of photos, looping, translation, dictionaries, and printing were not so present. Only 12% of the apps had recording capabilities, compared to 89% having narration and 45%, hotspots. Other more common functions were animation (92%), book narration, and rewards. Similar to narrative, research found that hotspots that were not tied with the rest of the educational content caused distractions (Takacs et al., 2015).

Familiar Characters

Research has found that having an engaging, recognizable character in educational television media could increase learning for a child (Calvert et al., 2014). We decided to check if the learning apps in our sample had a recognizable character. About 21% had someone like Elmo or a Mickey Mouse guiding the child through the app experience. Though not every app has the opportunity to feature Elmo or Mickey Mouse, the just quoted research does indicate that learning occurs when the character is similar to the child (gender, favorite activities) and when the behavior is personalized (speaking to a child, saying child’s name).

Multiple Accounts & Customization

We looked at various forms of customization options within each app and found that the ability to set the overall level of difficulty for a user (also known as “leveling”) was pretty rare with only 17% having that feature. Multiple accounts was also hard to find with only 24% of the apps containing the feature. Though there isn’t much research that indicate having these functions increase learning, it may be helpful to have multiple accounts for those families with more than one child in the family. Furthermore, customization and having the app suited towards the child’s learning needs in a variety of ways is always a benefit to learning.

Non-English

Shockingly, a mere 1.2% of the apps had other languages along with English (but without Spanish). And only about 15.3% had English, Spanish and other languages. This is somewhat disappointing since apps and other interactive media have particular attributes that could be leveraged for second language learning. These media have the ability to portray multiple forms of information at the same time—such as text on-screen, audio narration of text, and images—in addition to including the same information in multiple languages (August, 2012 as cited in Vaala, 2012). This potential is especially promising given the high documented rates of cell phone and tablet ownership and use among Hispanic families in particular, including those where English is not the primary language (Rainie, 2012; Zickuhr & Smith, 2012). Many Hispanic families report strong perceptions of the educational potential of media, including apps, for their children’s learning (Lee & Barron, 2015; Levinson, 2014).

Multiple Ethnicities

Having mentioned earlier that seeing characters that are similar to themselves is helpful for children’s learning and engagement, it’s interesting to see that just 27% of the apps in the sample contain multiple ethnicities. The majority of the apps (53%) had non-human characters potentially to avoid issues like cultural appropriation or mislabeling of characters. However, it is reasonable to expect that kids would also benefit from seeing diverse characters and those that are similar to themselves in the apps (Clark, 2008).

Above we capture just the few and far in between qualities we discovered in this jungle of apps. There are probably many more that aren’t as represented but equally as important to the learning experience of the child. It is through further additional research and evaluation could we uncover these rare birds.

Read the full study here.