I recently met Paul Darvasi and Aleksander Husøy at the annual UNESCO Forum on Global Citizenship Education in Ottawa, where we were on a panel hosted by the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Sustainable Development.

The subject of our panel was a debate on the topic, “Innovative pedagogies for ESD and Global Citizenship Education: Is game-based learning the future?” Both Paul and Aleks use games in the classroom often when they’re teaching and I’ve been creating them for the past nine years, so frankly, there wasn’t all that much debate on the stage about whether games in the classroom could be a valuable tool for learning!

The real questions we grappled with were: How can games be best created as tools for learning? and Can we convince more educators to use games as a tool to foster global citizenship education? We’ve been continuing our conversations post-conference, and are excited to share the discussion here. The first part of our conversation focuses on how Paul and Aleksander use games in their classrooms to inspire global citizenship and build relationships.

Inspiring understanding and empathy through games

Sandhya: During our panel, we talked about how games are a robust new medium that, when combined with literature, art, VR, and primary sources, can truly bring a curriculum to life. We talked about how they can take children and youth on digital excursions to better understand how other people live, serving as windows, doors, and mirrors for today’s youth.

Sandhya: During our panel, we talked about how games are a robust new medium that, when combined with literature, art, VR, and primary sources, can truly bring a curriculum to life. We talked about how they can take children and youth on digital excursions to better understand how other people live, serving as windows, doors, and mirrors for today’s youth.

You both use digital games in your classrooms to promote intercultural understanding, social responsibility, and global citizenship. How and why do you think games are an ideal medium for doing this?

Paul: Video games can transport players to other spaces, bodies, cultures, and time periods—all which involve shifts in perspective. Walking the proverbial mile in someone else’s shoes, whether a Nepalese farmer or a Kurdish refugee, provides insights that can encourage positive social attitudes and behaviors. Books, films, and other traditional media formats offer us views of other people and places, but each medium has unique advantages and disadvantages in how they transmit perspective. Film and TV are spectatorial, while video games are participatory in that they invite players to make choices, and their actions activate tangible consequences in the game world. This type of interactive engagement can more deeply invest players emotionally and cognitively in the content and, ideally, lead to changes in their attitudes and behaviors.

Paul: Video games can transport players to other spaces, bodies, cultures, and time periods—all which involve shifts in perspective. Walking the proverbial mile in someone else’s shoes, whether a Nepalese farmer or a Kurdish refugee, provides insights that can encourage positive social attitudes and behaviors. Books, films, and other traditional media formats offer us views of other people and places, but each medium has unique advantages and disadvantages in how they transmit perspective. Film and TV are spectatorial, while video games are participatory in that they invite players to make choices, and their actions activate tangible consequences in the game world. This type of interactive engagement can more deeply invest players emotionally and cognitively in the content and, ideally, lead to changes in their attitudes and behaviors.

Aleks: Compared to many students elsewhere, our students in Norway are fairly privileged. They live in a safe and stable country with access to education, health care, a generous welfare state, and a range of other benefits that they can take for granted. Though students are generally conscious that their own fortunate circumstances are not universal, it is difficult to understand the mindset of people whose lives are distant from their own.

Aleks: Compared to many students elsewhere, our students in Norway are fairly privileged. They live in a safe and stable country with access to education, health care, a generous welfare state, and a range of other benefits that they can take for granted. Though students are generally conscious that their own fortunate circumstances are not universal, it is difficult to understand the mindset of people whose lives are distant from their own.

Through games, players have the opportunity to put themselves into the shoes of others. My students get to experience the consequences of war and the breakdown of society from the perspective of a civilian. They can feel the emotional pain of refugees pleading to cross the border to safety in Papers, Please. Or they can witness the effects of parental neglect on a young child in Among the Sleep.

Emotional or compassionate learning, as I facilitate through games in my classroom, is not new to education. The experiences I want my students to have are not unlike what we strive for when reading fiction or watching films. When teachers assign novels like Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, they do so to give students access to an inside perspective on indigenous Igbo culture. Films like Schindler’s List and The Boy in the Striped Pajamas can provide proximity to the subject matter that I doubt is possible through even the most brilliantly written textbook.

As Paul raised, games have additional value that traditional media lacks– interactivity. While books and movies are passive, games place significant weight on the player. When reading, one might feel strongly about the choices characters should or should not make, but they cannot compel the story to change direction. When playing a game, the player is personally responsible for the choices that are made, which creates a stronger bond between the medium and the media consumer.

In This War of Mine, which is one of my favorite games for use in Social Science, the player takes on the role of a group of civilians caught in the middle of a conflict-ridden city. The player is directly responsible for their survival and needs to make a series of choices that challenge their personal views of right and wrong. Similar narratives exist in novels and film, but the feeling of real personal responsibility for the characters that the game evokes cannot be replicated by spectatorial media. These types of experiences are the reason why digital games in my mind have a place in the classroom.

Promoting digital collaboration across borders

Sandhya: The two of you had never met in person but the conference was like a reunion, because you’ve been collaborating around games in education for four years! Together you’ve developed a strategic approach to using games as literature and carried out programs where your students have collaborated closely through the use of tools such as Facebook, video calls, and shared documents. Can you tell us more about your collaboration?

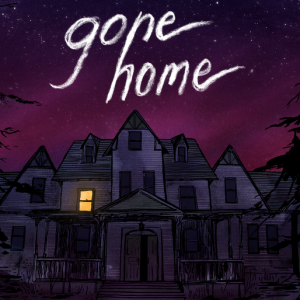

Paul: For the last three years, Aleks and I have run a collaborative unit between our classes in Canada and Norway. Our students play a narrative-rich video game called Gone Home and then undertake a series of transatlantic activities in response to the gameplay experience. We set up a private Facebook group where students introduce themselves with ice-breaking activities, and share their views and insights on the game. At the end of the unit, students have the option to participate in group projects that combine members from both countries. Despite the time differences and geographic separation, they have produced memorable final projects including zines, machinimas, video presentations, and podcasts. It’s not only a meaningful way to unpack themes and ideas about the game text— it’s also a valuable exercise in managing online international collaborations, a crucial skill in an increasingly globalized world.

Aleks: For my students, who are not native English speakers, having the opportunity to work with Paul’s classes is a great experience. In addition to the value of international collaboration Paul described, my students are afforded the additional benefit of taking part in productive communication with native English speakers. Though our students have never met in the flesh, the level of collaboration between some of our groups is at least on par with what I’ve seen from students who’ve travelled on short term (physical) cultural exchange programs.

What also strikes me about this project is how simply the logistics can be arranged. Though our project is centered on a game-based unit, I see few barriers to other schools running similar “digital exchange programs” on any topic with very little hassle. With Internet access increasingly available in schools worldwide, I hope to see many more similar projects elsewhere. Not all students have the opportunity to take part in cultural exchange programs, but through digital collaboration, many of the same benefits can be achieved.

Putting game-based learning in context

Sandhya: Both of you agree that games, by and of themselves, have no magical or miraculous properties and instead propose that their value comes from the context in which they are used. What has led you to believe this and can you each share an example from your classrooms to help us better understand what you mean?

Paul: Digital games are complex and dynamic systems that can produce a variety outcomes. Like all text, games can be interpreted in diverse ways. It’s important to contextualize gameplay in order to achieve specific learning outcomes. For example, I’ve used Total War: Rome II in a history class to study Caesar’s first battle in Gaul. Rome II is a sprawling strategy game that requires players to manage economics, policy, civics, military deployment, diplomacy, etc. It spans decades and spreads across huge geographic areas. However, for the purposes of this unit, we focused on a tiny slice of the game that features the earliest part of Caesar’s campaign in what is today the south of France.

Before playing, students read Caesar’s own account of the battle from his Gallic Wars and watched a short documentary on the topic. This helped fill-in background specific to the event and ultimately added to their understanding of the game. The goal of the unit, aside from learning about the historical event itself, was for students to think about how different sources represent historical events in contrasting ways. Students had the opportunity to examine and think critically about how books, films and games each have unique affordances and constraints in how they transmit history. This learning outcome was not determined by the game, but by the context. Most digital games can be used in any number of ways, so the context must be shaped to direct the learning, whether through discussions, additional readings, videos, or assignments.

Aleks: It should be obvious by now that both Paul and I are excited about the potential value of bringing games into the classroom. I do however see a disturbing trend, where developers of educational games peddle their products as near-mystical artefacts that will turn kids into the next Einstein or Mozart. As an instructor on the use of games in education, I’ve seen many classrooms where students are plopped in front of a game with the assumption that the game in and of itself is the key to mastery. My strong belief is that games should not be viewed differently than any other medium. Learning does not happen first and foremost through interaction between the learner and the game, but instead through interactions between the learner, the teacher, their peers,and other learning materials.

In Among the Sleep, which I have been using with students studying health and social care, the player takes on the role of a young child experiencing neglect and child abuse. Though the game itself delivers a powerful message, the most valuable part of the learning process is when students discuss their experiences from the game, contextualizing them with other parts of the curriculum as well as their experiences from work practice. Games can offer experiences that are difficult or impossible to replicate in the real world, but in the same way that teachers would follow up an excursion to a museum with additional activities, materials, and reflection, the activities that take place during and after a game-based unit are at least as important as the game itself.

There are a wide variety of games available, and an even greater variety of perspectives on how games should be approached in the context of education. Some games are designed for a learning process that happens primarily through interaction between the game and the player. However, in my mind, if a teacher uses class time on a game where interaction with peers or the teacher is irrelevant, they are not making good use of class time—or the opportunity for digital collaboration.

The conversation continues as Sandhya, Paul, and Aleks discuss the need for collaboration between teachers and game developers in Part 2 of their roundtable discussion.

Paul Darvasi teaches high school English and media studies at Royal St. George’s College in Toronto, Ontario and is a game designer and PhD candidate in York University’s Faculty of Education. He recently authored How Digital Games Can Support Peace Education and Conflict Resolution.

Paul Darvasi teaches high school English and media studies at Royal St. George’s College in Toronto, Ontario and is a game designer and PhD candidate in York University’s Faculty of Education. He recently authored How Digital Games Can Support Peace Education and Conflict Resolution.

Aleksander Husøy teaches English and social science at Nordahl Grieg Upper Secondary School in Bergen, Norway and is a teacher-instructor and advisor for the Norwegian Centre for Information and Communication Technology in Education.

Aleksander Husøy teaches English and social science at Nordahl Grieg Upper Secondary School in Bergen, Norway and is a teacher-instructor and advisor for the Norwegian Centre for Information and Communication Technology in Education.

Sandhya Nankani is a children’s media producer who creates content and narrative designs for educational games, including the recently launched “World Rescue”, inspired by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Sandhya Nankani is a children’s media producer who creates content and narrative designs for educational games, including the recently launched “World Rescue”, inspired by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.