The Interaction Design and Children Conference took place in June 2017 at Stanford University. The conference brought together a multidisciplinary community, focused on multiple aspects related to the design of technology for children.

The Interaction Design and Children Conference took place in June 2017 at Stanford University. The conference brought together a multidisciplinary community, focused on multiple aspects related to the design of technology for children.

As part of the conference, we put together a workshop to discuss Joint Media Engagement (JME) as it relates to the development and consumption of apps for children and their caregivers and peers. We framed the discussion around previous theoretical work done on this topic. We also considered primary research conducted at Google observing trends on parents and kids using apps together and building stronger bonds through joint media use. During the workshop, participants covered a range of topics related to JME, such as social interaction and child development, connecting hospitalized kids with family through virtual reality games, co-engagement with the natural world, role-playing and toys, as well as interactive robots.

Theory behind the workshop

Consider the following scenarios:

Scenario 1

Noah heard about the new Pokemon GO game from his friends at school and immediately downloaded it. As an 8-year-old, he uses his dad’s old phone to play games after school or during the weekends. His aunt is visiting, and he asked her to download the game on her own phone so he could teach her how to use it, and catch Pokemons together while they are out spending time together.

Scenario 2

Ana’s 11-year-old daughter loves to play Candy Crush Saga and is constantly talking about it with her friends. Ana decided to download the game on her phone and start playing as an opportunity to bond and connect with her daughter. She sometimes asks her daughter for help, even if she doesn’t really need it.

Scenario 3

Sara often lets her 6-year-old son and 3-year-old daughter play games and watch videos on her old tablet while she cooks dinner. Her kids have to share the tablet so they take turns and often fight over who gets to play first or what to watch. A family friend told Sara about the game Sago Mini Doodlecast. When Sara’s kids tried the app, they worked together on the drawings and enjoyed recording their voices. They were also excited to share what they made together with Sara.

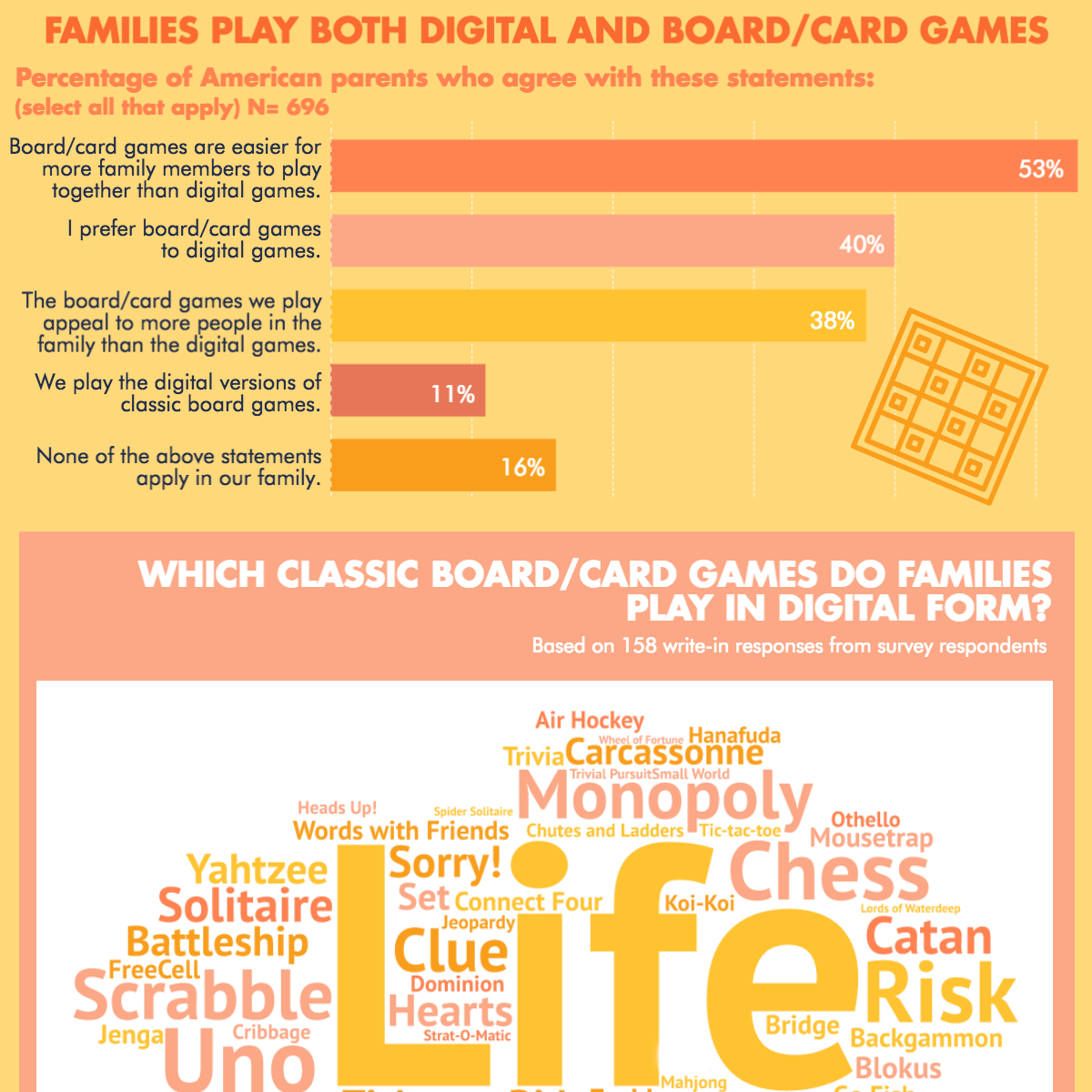

These scenarios are examples of case studies we have come across during our own research and practice, and represent different ways in which parents and kids are using mobile games to enrich both digital and real-life experiences. Together, they demonstrate how mobile games are no longer just a way for isolated users to spend free time, but are also instruments for social bonding and keeping abreast of each other’s interests. Recent research by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center supports that playing digital games together is growing in popularity, particularly among families with children age 4-10, and suggests that when it comes to kids and media, context matters (Joan Ganz Cooney Center, 2017).

In her book Screen Time, Lisa Guernsey writes about the importance of context, and how parents’ attitudes towards media matters (Guernsey, 2012). She encourages parents to consider what she refers to as the Three Cs—content, the individual child, and context— when selecting, using, and developing digital media with and for young children. When parents choose good content and coview/co-use digital media with their children, media becomes a way to enrich the relationship and connection between parent and child. Decades of research on television and young children, as well as emerging research on children’s use of digital media, also suggest that the educational value of media is enhanced when kids and parents use media together (e.g., Takeuchi & Stevens, 2011) because kids learn best in the context of interactions and relationships with tuned-in, caring and responsive adults (Donohue, 2015).

Although Guernsey’s Three Cs are the same in terms of their level of importance, context tends to be a more nebulous concept to grasp and design for. When designing technology for children, products tend to focus on providing content that is both engaging and appropriate for children at a given age and developmental stage. By purposefully including context as a design parameter for the design of technology for children, product developers can aspire to not only create engaging games, toys, books, etc., but also meaningful experiences and connections between children and their parents and peers.

Over the last six years, field leaders from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center, the Fred Rogers Center, and the TEC Center at Erikson Institute have produced a number of publications that provide insight into the context of conjoint technology usage and suggest various design strategies for encouraging co-engagement (e.g., Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College, 2012; Takeuchi, 2011; Takeuchi & Stevens, 2011; Vaala, Ly, & Levine, 2015). For example, creating content that challenges and appeals to both kids and parents, that can be played or used together. Other ways to encourage JME include extending play beyond the screen, connecting in-app experiences to the real-world, and encouraging communication with family members, caregivers, or friends. These design strategies provided the starting point for our workshop.

Outcome of the workshop

Our workshop participants used all the information outlined previously as a base to start a discussion on designing technology for children that fosters co-engagement. We formed smaller groups and discussed the topic based on three age buckets: Preschool (2 to 5 years), Early elementary (6 to 8 years), and Later elementary / Middle school (9 to 12 years).

At the end of the discussion, our takeaways were transformed into a series of guidelines that can be used by developers of children’s media who wish to foster co-engagement:

Preschool (2 to 5 years old)

- Provide tangible objects for play

- Activities that go from screen to real world

- Activities that are motivating to both children and adults

- Scaffolds for parents’ co-engagement

- Extended familiar play patterns or daily routines of parents and children

- Open-ended play to enable personal creativity

- Intuitive gameplay with minimal instructions

- Flexibility of design for both co-play and solitary play

- Distribution of roles and many points of access for play

Early Elementary (6 to 8 years old)

- Find ways to allow co-play between peers and parents with varying degrees of parental involvement. Help the child bring in the parent (passive co-engagement)

- Ensure rapid prototype test with kids and parents (“test early, test often”)

- Design for the kid’s context (consider their challenges)

- Allow kids to express themselves and share it with their peers on the platform (not social media)

- Include multiple roles, possibilities, and guidance; but allow for flexibility and the ability to play individually as well as with others

- Ensure the design is inviting to parents and compelling across ages

- Needs to be on a variety of devices, i.e.not tablet only

- Be visually driven, but some amount of text can be considered

Later elementary / Middle school (9 to 12 years old)

- Abstraction and shared understanding can be included at this age. Not everything needs to be spelled out, and parents and kids can work together to solve quests.

- Foster autonomy. Give more responsibility to the kids and less to the parents, allow kids to teach parents how to play games, solve quests, etc. Foster co-creation and play with others.

- Promote a higher understanding of one’s self. Foster confidence, guided mastery and adaptive feedback.

- Social sharing. Foster ownership of one’s achievements and failures by sharing creations and building on them or creating ways to start conversations.

- Show and tell to foster different levels of relationships.

- Understand parental roles at this age, and design optimal ways of involvement.

Next steps

This workshop was just our first step for starting the conversation on joint media engagement with a highly multidisciplinary group focused on the design of children’s media. The guidelines we crafted are an initial attempt to look deeper into this topic as it relates to different stages of child development and to provide guidance to developers of media who wish to offer co-engagement experiences in their products.

We definitely wish to continue the conversation and work on this area! You can join the group we created for this community here. And you’ll find more information on the workshop website.

References

Donohue, C (Ed.). (2015). Technology and Digital Media in the Early Years: Tools for Teaching and Learning. New York: Routledge and Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College. (2012). A framework for quality in digital media for children: Considerations for parents, educators, and media creators. Latrobe, PA: Fred Rogers Center

Guernsey, L. (2012). Screen Time: How Electronic Media—From Baby Videos to Educational Software—Affects Your Young Child. New York: Basic Books.

Ito, M., Baumer, S., Bittanti, M., boyd, d., Cody, R., Herr-Stephenson, B., … Tripp, L. (2010). Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning with New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Takeuchi, L., (2011). Families matter: Designing media for a digital age. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Takeuchi, L., & Stevens, R. (2011, December). The new coviewing: Designing for learning through joint media engagement. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

The Joan Ganz Cooney Center. (2017, January). [Digital Games and Family Life: Families play both board/card games and digital games together] [Infographic]. Retrieved from http://www.joanganzcooneycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/JGCC-DGFL-4.pdf

Vaala, S., Ly, A., & Levine, M.H. (2015). Getting a read on the app stores: A market scan and analysis of children’s literacy apps. New York, NY: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Catalina Naranjo-Bock is a Senior User Experience Researcher at Google Play, where she leads the Kids & Family UX research vertical. Prior to joining Google, Catalina led product research and design at the LEGO Group, Nickelodeon, Yahoo, and YouTube. She holds and MFA in Product Design and Human Computer Interaction (HCI) from the Ohio State university. Catalina has also served as an advisor at Stanford University, University of Berkeley, and the California College of the Arts.

Jennie Ito, Ph.D. is a Policy Expert for Google Play, focused on the Kids & Family section of the app & games Play Store. She has a Ph.D. in developmental psychology from Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada, with a specialization in children’s play and social cognition. She began her career as a Fellow in Museum Evaluation and Museum Education at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. Prior to joining Google, Dr. Ito had her own play and toy consultancy where she reviewed toys and helped toy and media companies such as LeapFrog, Coolabi, and Peaceable Kingdom create meaningful play experiences for young children.

Jennie Ito, Ph.D. is a Policy Expert for Google Play, focused on the Kids & Family section of the app & games Play Store. She has a Ph.D. in developmental psychology from Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada, with a specialization in children’s play and social cognition. She began her career as a Fellow in Museum Evaluation and Museum Education at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. Prior to joining Google, Dr. Ito had her own play and toy consultancy where she reviewed toys and helped toy and media companies such as LeapFrog, Coolabi, and Peaceable Kingdom create meaningful play experiences for young children.