I remember looking under the television set for the legs of the colorful, English-speaking monsters from Sesame Street. Back then, our TV set had four legs on a wooden box and stood in the middle of the tatami living room at my home by the Sea of Japan. I dreamed about going to America one day to meet those furry monsters and seeing their whole bodies.

Sesame Street began broadcasting in Japan in 1971. Many in my generation learned English from the show. Today, as the General Manager for Sesame Street Japan, I am reimagining the brand and building it. We’re going back to the program’s roots in education, combining it with technology to scale and gathering evidence to teach. Our goal is to introduce the “whole child (pun intended)” framework of Sesame Street education. We are challenging Japanese kids with questions that have no right or wrong answers, like “what is your dream?” Who would have thought that the kid in front of the four-legged TV set would be pursuing his dream half a century later in New York in this way?

Eventually, I moved to America, and after life’s many twists and turns, I was hired as a producer in 2003 to launch the Japanese version of Sesame Street. Like all other international co-productions of Sesame Street, the Japanese version had a localized educational goal, and back then, it was “respect for nature.” I felt a very Zen-like enlightenment and fulfilled because I was able to contribute to the education of kids in my birth country. The show featured several local characters dealing with local customs and beliefs like “spirits in chopsticks” —a much longer story that I’ll save for another article. On the set, there was a convenience store and a big tree in the plaza where everyone gathered, for around that time, 7-Eleven and local convenience stores occupied every corner of Japanese streets, a cultural evolution of the era. We had a good run for four years with our partners in Japan, producing and promoting a local version of Sesame Street.

English education was something I was interested in from my childhood, and I began pursuing the idea of using Sesame Street to teach English as a foreign language more systematically rather than as a subset of an American show to teach ABCs to preschoolers. For a few years, we looked for investors from around the world. I remember desperately writing a haiku poem to court a Japanese investor while on a plane to Tokyo.

Sing and dance [with us]

When [you] begin dreaming [in English]

Your dream has already come true

I promise it sounded much nicer in Japanese, and it worked. We received a major investment from a Japanese afterschool program provider to create a Sesame Street English program for kids from 3 to 18.

The production lasted 10 years. Then, when smartphones and tablets hit the market, we had to adapt to accommodate new technology, including adaptive learning, big data, AI, and so on. It was no longer about how a kid like me in front of a four-legged TV set could learn English by repeating Oscar as he screamed “Scram!” We had to design interactive lessons for touchscreen monitors where kids were instructed to trace “scram” with a finger, collecting data on the back end. Singing and dancing and touching screens helped. Today, there are over 500 Sesame Street English schools in Asia.

The production lasted 10 years. Then, when smartphones and tablets hit the market, we had to adapt to accommodate new technology, including adaptive learning, big data, AI, and so on. It was no longer about how a kid like me in front of a four-legged TV set could learn English by repeating Oscar as he screamed “Scram!” We had to design interactive lessons for touchscreen monitors where kids were instructed to trace “scram” with a finger, collecting data on the back end. Singing and dancing and touching screens helped. Today, there are over 500 Sesame Street English schools in Asia.

There is more. As we were wrapping up Sesame Street English production, we entered the Japanese formal education sector with “Dream, Save, Do: Financial Empowerment for Families (DSD),” a Metlife Foundation-funded global initiative that taught how the choices kids make every day can help them achieve their dreams. After a few devastating natural disasters that took place around that time, Japan was facing serious financial and regional disparity, and inequalities in what we used to think of as a nation of average middle class. Today, Japan has one of the highest child poverty rates in the world, a very low birthrate, and the whole country is aging.

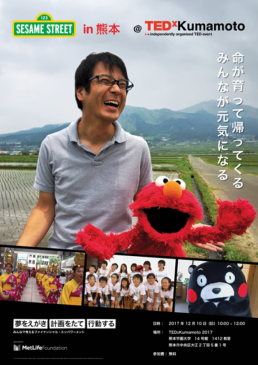

We took the DSD program everywhere from the northern island of Hokkaido to the southern tip of Kyushu Island, visiting schools and communities. We collaborated with Kumamon, one of the most popular Japanese bear characters of Kumamoto prefecture where the earthquake destroyed the city, displacing kids and families in temporary housing. Elmo sang a rap song with the rapper-turned-Mayor who hosted our workshop in a snowstorm in Akita. But after three years of grassroots efforts, it was not scaling the way we envisioned with only one school district, Toda City in Saitama, implementing the program.

We took the DSD program everywhere from the northern island of Hokkaido to the southern tip of Kyushu Island, visiting schools and communities. We collaborated with Kumamon, one of the most popular Japanese bear characters of Kumamoto prefecture where the earthquake destroyed the city, displacing kids and families in temporary housing. Elmo sang a rap song with the rapper-turned-Mayor who hosted our workshop in a snowstorm in Akita. But after three years of grassroots efforts, it was not scaling the way we envisioned with only one school district, Toda City in Saitama, implementing the program.

We decided to add an online course for families, thinking that it could bridge the missing link between schools and homes, and scale wider to reach an underserved population. Then, the COVID pandemic hit, presenting a timely opportunity to test the Online Course for Families for all kids in Japan who were ordered to stay home for quarantine. We were able to recruit over 150 families right away to participate in the pilot test. This was by far the most unexpected and unprecedented event that challenged us to rethink how we provide education to kids who are stuck at home while teachers, schools, and whole districts were struggling to come up with a plan to fill the void. They had no content that dealt with social-emotional learning and had no idea as to how to teach these subjects without human interactions, or teachers who are trained for online sessions.

We decided to add an online course for families, thinking that it could bridge the missing link between schools and homes, and scale wider to reach an underserved population. Then, the COVID pandemic hit, presenting a timely opportunity to test the Online Course for Families for all kids in Japan who were ordered to stay home for quarantine. We were able to recruit over 150 families right away to participate in the pilot test. This was by far the most unexpected and unprecedented event that challenged us to rethink how we provide education to kids who are stuck at home while teachers, schools, and whole districts were struggling to come up with a plan to fill the void. They had no content that dealt with social-emotional learning and had no idea as to how to teach these subjects without human interactions, or teachers who are trained for online sessions.

We thought we could help, but we were wrong once again. The research indicated that more financially privileged families participated and there was no evidence that we reached those intended target populations from diverse backgrounds.

That is when I reached out to Dr. Michael Preston, the Executive Director at Joan Ganz Cooney Center about “Learning Engineering.” To fill the gap, scale and reach a wider population, provide social-emotional content, and gather meaningful data that we can give educators to use, we were convinced that we needed to come up with a hybrid teaching model and Plan B for when the schools are shut down entirely for a long time.

Concurrently, to promote our curriculum, we had launched the Sesame Street Education Summit in 2019 and were beginning to tour the country to different cities when COVID prohibited anything physical on a large scale. We had no choice but to move the Summit online with keynote speakers, Mr. Tsutomu Togasaki from the Toda City Board of Education, the first city that implemented the DSD-inspired Sesame Street Curriculum to talk about their on-the-ground battle with COVID and implementing online education in their district; Dr. Noriyuki Inoue from Waseda University to talk about formative research and Sesame Model; and Michael, who spoke about Learning Engineering and how US schools have been dealing with online learning through COVID. The summit was successful in that we were able to gather more people from all over Japan than otherwise possible in a physical space, and gave us clues for the next steps in preparing for an in-person summit.

Concurrently, to promote our curriculum, we had launched the Sesame Street Education Summit in 2019 and were beginning to tour the country to different cities when COVID prohibited anything physical on a large scale. We had no choice but to move the Summit online with keynote speakers, Mr. Tsutomu Togasaki from the Toda City Board of Education, the first city that implemented the DSD-inspired Sesame Street Curriculum to talk about their on-the-ground battle with COVID and implementing online education in their district; Dr. Noriyuki Inoue from Waseda University to talk about formative research and Sesame Model; and Michael, who spoke about Learning Engineering and how US schools have been dealing with online learning through COVID. The summit was successful in that we were able to gather more people from all over Japan than otherwise possible in a physical space, and gave us clues for the next steps in preparing for an in-person summit.

The year 2021 will be Sesame Street in Japan’s 50th anniversary. We will be kicking off with another Sesame Street Education Summit Online II event with speakers from Google and Coursera from the USA, and experts from Japan to talk about Platform UX, Content Strategies and Teacher Training to debate if our hybrid model and its Plan B will have a future, as we continue asking questions that have no right or wrong answers.

Singing, dancing, and touching screens — what else will be needed to make one’s dream come true?

An international executive with over 25 years of experience in more than 20 language markets in brand management, international co-productions, and other business ventures, Manabu Nagaoka is the VP and General Manager of Sesame Street Japan and Head of Sesame Street English. As a highly creative and entrepreneurial executive producer, Nagaoka has produced a variety of properties and media content including feature film, television, music, advertising, theater, and digital/interactive media. He has an MA in Education (TESOL) and BA in World Arts and Cultures, trained in cross-cultural and interdisciplinary research, curriculum design, media production, computer science, and game-play theories.

An international executive with over 25 years of experience in more than 20 language markets in brand management, international co-productions, and other business ventures, Manabu Nagaoka is the VP and General Manager of Sesame Street Japan and Head of Sesame Street English. As a highly creative and entrepreneurial executive producer, Nagaoka has produced a variety of properties and media content including feature film, television, music, advertising, theater, and digital/interactive media. He has an MA in Education (TESOL) and BA in World Arts and Cultures, trained in cross-cultural and interdisciplinary research, curriculum design, media production, computer science, and game-play theories.