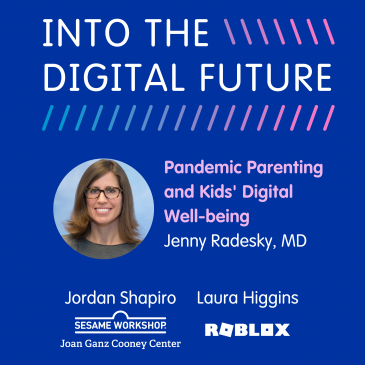

This transcript of the Into the Digital Future podcast provides excerpts of the conversation that have been edited for clarity. Please listen to the full episode here.

Dr. Jenny Radesky is a Developmental Behavioral Pediatrician and Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School. She received her M.D. from Harvard Medical School, trained at Seattle Children’s Hospital and Boston Medical Center, and her clinical work focuses on autism, ADHD, and advocacy. Her NIH-funded research focuses on the use of mobile and interactive technology by parents and young children, which she tries to translate into practical parenting advice. She was the lead author of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statements Media and Young Minds in 2016 and Digital Advertising to Children in 2020.

Laura Higgins: On today’s show, we’ve got Jenny Radesky. She’s a developmental behavioral pediatrician at the University of Michigan, and a researcher who focuses on the relationships of devices and young people and how all of that works. This was a really fascinating introduction to her extensive amount of work. She is extremely well respected and very very knowledgeable.

Jordan Shapiro: One of the things that I’ve always loved about Jenny’s work, and that she really does express in this interview, is that so much of what you hear when people focus on kids’ wellbeing and digital use becomes a zero-sum game. It’s either good or bad. Jenny is really realistic about it. Devices are here, and we need to focus on kids’ wellbeing and how to think about different questions in the design of platforms. The whole conversation is fascinating.

….

Jenny Radesky: I am Jenny Radesky. I am a developmental-behavioral pediatrician at University of Michigan. I am also a researcher. I tend to look at things through the lens of how kids’ tech design aligns with their best interests rather than trying to see things from the perspective of what are parents doing wrong or how is tech melting kids’ brains? And I’ve been really actively involved with the American Academy of Pediatrics, who put out the screen time guidelines, which I was a lead author on in 2016, as well as the Digital Advertising to Kids Policy statement in 2020.

Laura: I’ve always been really impressed with the articles you do for PBS. You do fantastic, really straightforward advice for parents. What sorts of things do you think we should all be talking to parents about? What do they need to know right now?

Jenny: My overall big picture interpretation of all of this dependence that we and our kids now have on technology is that, if we need either extra time for our kids to be occupied or exploring a digital space, I want to direct families towards the most positive places.

Jenny: My overall big picture interpretation of all of this dependence that we and our kids now have on technology is that, if we need either extra time for our kids to be occupied or exploring a digital space, I want to direct families towards the most positive places.

I don’t love using the word safe because “safe” always makes parents think about pedophiles and things like that — so what I mean more as safe, is that it’s some place that respects their exploration and their autonomy. It isn’t trying to just feed them a commercial after a commercial, or isn’t just trying to exploit their attention to make more ad revenue.

Laura: If you could give one piece of advice right now for a parent who’s pulling the hair out, is that one thing that you could really point them towards?

Jenny: Just talk about it. So, if you are a more lax parent who loves your kid figuring out new stuff online, you still want to be talking with them about what they have found. What are the coolest things they’ve found? What are the creepiest things they’ve found? And let them know that you’re a sounding board, a safe place to come and unpack these things with you.

If you’re more of a restrictive parent or someone who’s a bit more anxious about what the effects of tech use is going to be on your child, I’d say be a little bit more open minded towards broadening the amount of technology that they can use. But again, do it with them. See the space that they’re going to be playing in. First, play it with them.

I like the term mind-minded. It’s a research term for when we think about attachment. So the more a parent is mind-minded about their child’s emotional state, the more they understand the emotional drivers underlying a difficult or challenging behavior. So if you see a tantrum or you see someone throw food, if you’re mind-minded, you might think, oh, you know, ‘he’s done, he’s not hungry anymore’ or ‘he’s frustrated because he’s in a stage where he wants to put on his shoes by himself.’ If you’re not mind-minded and you’re just reactive, you’re just thinking, ‘God, he’s so terrible’ or ‘why is he torturing me like this?’ That’s where you’re showing the child that their strong emotions are triggering to you or that you can’t handle their strong emotions. So it’s hard for them to then learn how to handle them too.

To go back to technology, I think there’s part of entering a digital world with your kid where you can build a little bit of mind-mindedness about how they see tech. There’s the cool things where you realize, “wow, I didn’t realize he knew how to do that.” At the same time, you can also see, “oh, wow, you really don’t get that advertising,” or “you *totally* are such a sucker for those extra rewards that that free video game is trying to pack in so you make some in-app purchases.” So at least you get to know the strengths and limitations of your child’s mindset with regard to technology.

If we can just have one learning experience and growth experience from this whole crazy time of the pandemic, I think it could be understanding our kids’ relationships with technology better. Through co-play, but also some of these discussions, and just this observing and mind-mindedness.

I want to also acknowledge that me saying, “oh, just simply talk to your kids about this” itself is an assumption that parents have the time or bandwidth or aren’t dealing with multiple different stressors that impact the amount of time they have to just calmly sit with their kids and talk.

So, how could tech platforms or games encourage [wellbeing]? One way is to actually communicate with the parents about the way to make the most out of what your child is doing. Some of it could be built into the actual game design or interface design.

We just wrapped up a study where we were asking children 5-10 about their conceptualizations of digital privacy. What does this game, or YouTube, or your favorite game, or a website, know about you? And how does it know that? And where does it store it? And, the kind of inferences that might be made about children from their online behavior.

And one of them said, “oh, well, I know that I should have a password and a username, that’s not my actual thing, because Roblox taught me that.” And I was like, that’s cool that somewhere in the user experience there was a teaching moment that just happened naturally to the child.

I know that’s digital privacy skills 101. But couldn’t there be more? Couldn’t there be more things that the child could learn from your interface to know what is known about them or how the data are stored?

Laura: I spend a lot of time with the community and listening to the slightly aged-up community on Roblox. We are having those conversations like, “What would have made this bit easier for you? What would have helped with your understanding?”

I’m lucky I get to work with engineering and product and safety and all those teams. So we’re going to have a lot more of that immersive learning experience right through the journey when people first sign up. And actually we’re working with lots of other industry partners because, particularly in the gaming industry, they’re really keen to use this as a really positive thing. So watch this space!

Jenny: Part of my overall thinking about kids and health and technology, is that if we improve the design of this digital space and the digital ecosystem to make it child-centered by default, and to make it transparent and help even build digital literacy skills *as* you’re exploring that space, you’re really doing so much more on an ecosystem scale than each individual parent could do in their own households. And it’s actually more equitable too.

One of the things I’ve written about lately is this idea of Tom Frieden’s health impact pyramid. He was the CDC director under Obama, and he wrote this paper in the American Journal of Public Health talking about how at the very tippy-top of the pyramid where you have a lot of individual effort that needs to happen to make change happen. But you actually have the lowest yield in terms of your impact on a population health level.

At the tippy-top is parents trying to change their individual behavior or their child’s behavior, or a clinician like me giving guidance to someone in clinic: “Here’s how to exercise more. Here’s how to eat healthier food.” But if you’re actually at the bottom of the pyramid, and you change some of the socioeconomic and structural issues that lead to differences in opportunities, or if you change the health context to make your default decisions healthier, then you’re going to have much more population health impact with smaller individual effort needed. And this is the difference. It’s been used a lot in the food policy area. If you just can take trans fats out of all of the food in New York City, the whole population will benefit.

The same thing could happen in digital spaces too. If there’s more agreement amongst different industry partners to kind of have some child-centered design approaches that are not exploitative – they’re really empowering the child, they’re transparent – you’ll have kids just naturally doing the default thing in a healthier way or a more digitally literate way. Anyway, that’s my aspiration, I want to stop telling parents what to do!

Jordan: You just spoke a bit about your new research around data collection and privacy. I know you also looked at YouTube content, and I wonder if you could talk about how that plays in. Because I know a lot of people are really worried about YouTube content.

Jenny: YouTube was not a platform or a space designed for kids, and they’ve tried to retrofit it in a couple of different ways, but it’s not there yet. And that report that we put out with Common Sense Media in November, was an example of the sort of research that I’ve been trying to do lately. Which is to say, ‘what are kids being offered when they enter the App Store? Or when they enter YouTube? Or when they download the most commonly downloaded apps for kids 5 and under?’ These have been a couple of my studies: what is the design of those digital experiences that they’re having? Are they meeting our policy expectations when it comes to privacy and data collection?

The study we did in JAMA Pediatrics, where we analyzed the data flows from over 400 apps played by preschoolers – many of these apps were not designed for preschoolers! They were like for grannies, or some gambling apps we even found. But kids like them – they’re exciting. And it’s hard because, if you have this agnostic view towards age in the digital spaces that kids are entering, the producers and platforms don’t know if it’s a kid. So they’re treating them like they’re a general audience, and then they’re collecting private identifiers and sending them to big data warehouses like Facebook Graph.

So part of my research has just been to say ‘look at the mess that exists here. Can we clean this up? Can we not just take all of these adult design norms and slap them onto kids’ products and think it’s OK?’ I don’t want to just highlight the mess, though. What we did with the YouTube report (see also: 10 Steps to a Better YouTube) was to also try to highlight which YouTubers are doing this really, really well. Art for Kids Hub is one example that is role modeling such positive parent-child interactions — and not in a super sticky, sweet kind of perfect parenting way, like a real-life way.

So we wanted to highlight those, but also to raise the consciousness, both at YouTube and [among] parents, that a lot of these really positive channels aren’t getting the most views. The ones getting the most views are often really sassy, kind of ridiculous, kind of extreme, or very filled with branded content, because that’s what gets more clicks. And so, how can we rethink what’s elevated or surfaced on a platform like YouTube that’s going to influence what a child sees first when they get there?

Laura: One of the questions I had was around the responsibility of tech companies. So you’ve touched on some really quite specific things. We were talking a bit about safety by design models. What do you think in terms of pre-moderating content? There’s a lot of discussion here in the UK, for example, about the online harms and age-appropriate design code. What do you think we should be doing better?

Jenny: I think, to approach child-centered design across industry, 1) it involves having personnel on your teams who have experience with kids. They might have been educators, they might have a health background or a therapy background or something where there’s been larger contextual knowledge about kids, families, relationships, and the psychosocial factors that impact the way kids are going to engage with your product. Because you may be designing for a thin slice of the type of kids, but it may be used very differently and it may land differently in communities and users who are different – in positive or negative ways. You can’t anticipate every single negative or positive way your product might be used.

2) Could there be a larger panel or pool of experts that could be tapped into? I’ve talked with other academics who work in child computer interaction or child media research [to ask] how do we intersect with industry in ways that don’t just make us seem like I’m a consultant and therefore I’m biased. I’ve talked with folks like Common Sense Media or other larger organizations to see how we could help designers who want that input and don’t have a place to get it.

3) is a re-evaluation of metrics of success, which is the hardest. So right now in industry, the metrics of success are mostly about engagement with a digital product (number of times coming on per day, duration, etc.) But that doesn’t always align with what the child needs in real life. And it might be not aligning with their need for sleep or for family routines or for going along with other either unplugged activities or other digital activities like their virtual school.

Laura: So I get the last question, and I’ve asked all my guests this. A crystal ball moment for you: what do you think we’re going to see? Some big innovations or changes in the next couple of years?

Jenny: I see parents as being really much more aware and interested in all the inner mechanics of what’s going on with tech. Or maybe I’m just interested in helping them be more aware with digital literacy, or you could call it pulling the curtain back a bit and knowing how design choices are shaping their children’s behavior or their own usage behavior. Standing up and resisting a bit of the stuff that’s exploitative, and being less stressed out about the stuff that’s actually designed with their needs in mind. Or becoming a bit more conscious consumers about what products are really out there, that are really human-centered and which ones are profit-centered.

I’m not going to sugarcoat virtual learning and lockdown. This is the hardest parenting experience I’ve ever had. I’ve increased my clinic times so much just to be listening to what so many families are going through. There’s got to be something that we grow with out of this. And I hope one thing is finding, what is our relationship with these tech tools that we’re using every day and how do we make them better and use them better?