Augmented reality (AR) allows users to see and interact with virtual objects while still seeing their environment. AR is increasingly becoming more common and is being applied to gaming, healthcare, and education. For example, if you have ever played the worldwide phenomenon Pokémon Go, then you have used an AR application, with which you saw and collected virtual Pokémon in your environment.

AR applications can be created for a variety of devices, including smartphones, tablets, as well as headsets. Compared to hand-held devices, AR headsets provide mobility and hands-free capabilities, which increases user immersion and freedom. AR headsets are beginning to enter consumer markets, and children are starting to use them in classrooms, museums, and at home.

However, if you are interested in designing new AR headset experiences for children, where should you start? Now that it’s becoming more common for children to use AR headsets, we need to know how children think about these devices and their expectations so we can design better experiences for them. If a child tries to use an AR headset and it does not match their expectations, it can lead to errors, frustration, and even device or application abandonment. Also, it has been well-established that children often interact differently with technology and have different expectations than adults.

Recently, in collaboration with my colleagues from University of Florida and University of Washington, we examined how children think about AR headsets. We conducted four online participatory design sessions over Zoom with KidsTeam UW, which is an intergenerational co-design group from the University of Washington led by Dr. Jason Yip, one of my colleagues in this project. KidsTeam UW consists of children (ages 7 to 12) and adult design researchers that partner together to design new technologies for and with children.

For the design sessions, we focused on designing content for AR headsets with an emphasis on using them for everyday tasks (e.g., any kind of job, chore, or project). We wanted to see what types of tasks the children would be interested in using AR for and how they want the devices to help them in these tasks. The four remote design sessions included:

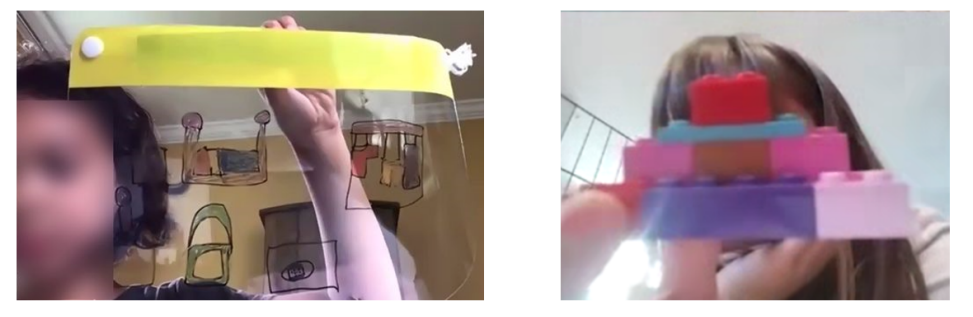

- Day 1: Design an AR headset game (using craft materials and Google Slides)

- Day 2: Design elements in an AR headset that would be helpful while using Legos (using craft materials, Google Slides, and Legos)

- Day 3: Create a story of using an AR headset for doing a task (using Google Slides)

- Day 4: Finish a story of using an AR headset for one of the tasks from Day 3 (using Google Slides)

We found that children expect highly intelligent AR systems that accept a wide range of input options (e.g., speech, body motion), can recognize and virtually transform their surroundings, provide real-time guidance and suggestions, create immersive environments, and allow them to experience things they could not do in real life. For example, in the quote that led to the title of our paper about this project, one 12-year-old boy said, “I think it would be cool to get stampeded by dinosaurs.” Also, children are in favor of using the headsets for games and difficult tasks, but did not feel they would be useful when they are trying to be creative or when completing easier tasks. As one 8-year-old boy commented, “If people get along easily without it, why do we need it?”

What does this mean for designing future AR experiences for children?

Through examining the children’s designs and how they think about AR headsets, we provide some insights for creating AR headset experiences for children:

- Consider location of objects in display: Based on the children’s designs, we noticed that they expect virtual objects to be on the right-hand side of the AR headset display; however, in past studies, people (adults) have been shown to have a leftward bias, leading to faster detection of objects that appear on the left-hand side. Children’s expectations may be stemming from prior experience with heads-up displays in games and entertainment on other devices they have used. In your designs, when deciding where to place objects in the headset display for children, consider this trade-off between increasing noticeability in general (maybe for more important information) or matching the children’s expectations.

- Provide support only for difficult tasks: We found that children did not want help and guidance from the AR headsets when they thought they could easily do a task themselves. Therefore, when designing AR headset experiences for children, take into account children’s desires to accomplish tasks on their own and only provide support in AR headsets if they are having a hard time.

- Avoid hand gesture commands: The children primarily designed interactions with virtual objects in the AR headset that used speech and body motion. One 10-year-old boy said, “I think it [voice input] would be easiest to do like, um, on short notice. Um, because like, you don’t have to take time to like touch something.” The children rarely thought of interacting with AR objects through specific gesture commands, although this is common in current AR headsets.

- Allow for extensive movement: We found that the children wanted to interact with virtual objects through body motion, such as ducking and dodging virtual cars, fighting, and running. Also, the children wanted to use the AR headsets both indoors and outdoors. Therefore, it is important to allow for extensive mobility, design on-screen information to be visible even in high-sunlight conditions, and plan to recognize whole-body input for AR headset experiences for children.

If you are thinking about how to use or design future AR headset content and experiences for children, we hope these insights will help!

Check out our full paper here.

Julia Woodward, Feben Alemu, Natalia E. López Adames, Lisa Anthony, Jason C. Yip, and Jaime Ruiz. 2022. “It Would Be Cool to Get Stampeded by Dinosaurs”: Analyzing Children’s Conceptual Model of AR Headsets Through Co-Design. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’22), April 29–May 05, 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3501979

This work is partially supported by National Science Foundation Grant Award #IIS-1750840 and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1842473.

Julia Woodward is a PhD Candidate in Human-Centered Computing from the University of Florida, as well as a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow. Her research areas focus on examining how to design visual information in augmented reality (AR) headsets for both adults and children, and understanding how to design technology to fit children’s perceptions and interaction behaviors. She will be joining University of South Florida in Fall 2022 as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering.

Julia Woodward is a PhD Candidate in Human-Centered Computing from the University of Florida, as well as a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow. Her research areas focus on examining how to design visual information in augmented reality (AR) headsets for both adults and children, and understanding how to design technology to fit children’s perceptions and interaction behaviors. She will be joining University of South Florida in Fall 2022 as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering.