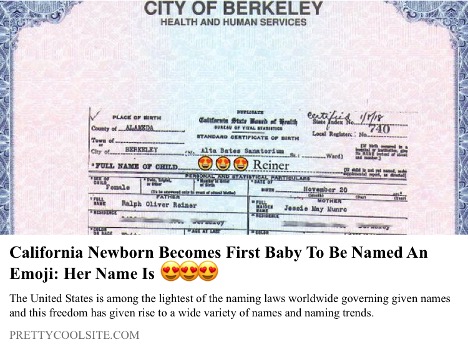

In February 2019, a story titled “California newborn becomes first baby to be named an emoji” circulated widely on social media. The story claimed a mother had named her baby the emoji equivalent of “heart-eyes heart-eyes heart-eyes.” It was fake and could be recognized as such by either its content or its source: prettycoolsite.com. Still, this story was shared on social media thousands of times, and some of those who shared it were likely children.

Most US elementary-school-aged children have access to the internet, which they use to watch videos and play games. These activities are typically mediated by content-streaming platforms, like YouTube and TikTok, or social media platforms, like Instagram and Snapchat. Are children prepared to navigate this new information landscape?

Recent research suggests not. Many elementary schoolers think that information found on the internet is generally accurate and that the credibility of a website can be gleaned from its appearance. When searching for information online, they are indifferent to whether a website contains inaccuracies or exaggerations. Elementary schoolers are also poor at differentiating fake news from real news. A national survey of elementary schoolers in the UK found that only 3% were able to identify which of six news stories were real and which were fake.

Older children do not fare much better. Many middle schoolers are unable to identify hoax websites on male pregnancy or the Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus, and most middle schoolers have trouble explaining why sponsored content from a bank might not provide objective financial advice or why the comments below a news article should not be included in a research paper. Most middle schoolers also have trouble discriminating online news stories from sponsored advertisements. Even high school students tend to evaluate the credibility of a source based solely on what the source has posted about itself.

Is it the medium or the message?

These problems, at first glance, appear to be a symptom of childhood credulity: children are susceptible to online misinformation because they are susceptible to misinformation in general. But studies of children’s ability to identify dubious information indicate that children are not credulous, not even as preschoolers. Their susceptibility to misinformation is likely driven by the medium rather than the message.

For instance, when children encounter implausible information offline, in a conversation or storybook, they are highly skeptical. Children as young as three easily recognize when events violate physical laws and judge such events impossible. They also recognize that people cannot violate physical laws and reject stories in which people grow smaller, stay awake forever, walk through a wall, walk on the ceiling, turn into ooze, or float in the air.

If children do err when reasoning about possibility, they err on the side of judging too little possible. Young children not only deny the possibility of events that violate physical laws but also deny the possibility of events that violate mere regularities—events that are improbable but not impossible, like drinking onion juice or finding an alligator under the bed. Young children claim a person could not own a pet unicorn in real life, but they also claim a person could not own a pet peacock; they claim a person could not make lightning-flavored ice cream in real life, but they also claim a person could not make pickle-flavored ice cream. Children’s tendency to judge improbable events impossible has been observed across contexts, cultures, and instruction.

These studies indicate that when children judge the possibility of real-world events, they are neither fully credulous nor fully astute. They base their judgments of whether something could happen on their expectations of whether it would happen without much reflection. Children’s early skepticism is thus broad but shallow, making them vulnerable to persuasion.

Consider children’s belief in Santa Claus. Children are aware of Santa’s impossible properties, but they accept his existence on the basis of social pressure from family, friends, and other members of their community. The more children are encouraged to believe in Santa, the longer and stronger they do believe. Children may be disposed to reject claims that violate their expectations, but that disposition can be overridden by social cues to the contrary.

Not all social cues are persuasive, though. Children scrutinize who to believe just as they scrutinize what to believe. When confronted with two informants asserting contradictory claims, children as young as two side with the informant demonstrating greater accuracy, knowledgeability, or competence, and they make such assessments when considering a variety of claims, such as claims about the names of objects, the functions of tools, the rules of games, or the locations of toys.

Sophisticated, yet naïve

Accuracy and knowledgeability are not the only cues children take into account, however. They also consider superficial cues, such as how attractive an informant is or whether they speak with a foreign accent. Children are particularly swayed by whether an informant’s claims are written down. As soon as children can read, they defer to text as an authoritative source of knowledge and privilege written information over oral information. Even children who are poor readers themselves side with written assertions over oral ones.

Writing also overrides children’s inclination to reject implausible claims. If, for instance, they are shown a hybrid animal that looks mostly like a bird and partly like a fish, they will accept that the animal is a fish if labeled “fish.” Children who are simply told the animal is a fish reject that assertion, insisting that it is a bird instead. Children’s willingness to trust text over their own intuitions is potentially problematic when applied to the internet, where all information is conveyed by text, accurate or not.

These findings indicate that children are epistemically sophisticated in some ways but naïve in others. They exhibit a healthy dose of skepticism in the face of implausible claims and unreliable informants, but they can be persuaded to change their minds by the trappings of authority and authenticity. Such trappings abound on the internet, where children encounter websites, videos, and social-media posts designed to legitimize implausible content with professional-looking formatting and mask unreliable sources with professional-sounding credentials.

While children have strategies for identifying dubious information, those strategies are not particularly helpful on the internet. Children are adept at diagnosing the epistemic credentials of the people around them, but such information is unavailable when evaluating text detached from the person who wrote it. And text on the internet often has the sheen of established fact. Misinformation appears in the same feeds as true information, rendering it more similar to the testimony of an authority than the conjecture of a peer.

The strategies children need for detecting misinformation on the internet are different from those they use in daily life. They need strategies like “lateral reading,” or verifying information across multiple websites, and “critical ignoring,” or disengaging with an online source at the first sign of deception. The internet is a powerful tool for learning, which even novice internet users recognize. But the internet presents information in a way that thwarts children’s natural defenses against misinformation, requiring them to learn new strategies tailored specifically to this new medium.

Andrew Shtulman is a Professor of Psychology at Occidental College in Los Angeles. He studies conceptual development and conceptual change and is the author of Scienceblind: Why Our Intuitive Theories About the World Are So Often Wrong (Basic, 2017) and Learning to Imagine: The Science of Discovering New Possibilities (Harvard, 2023).