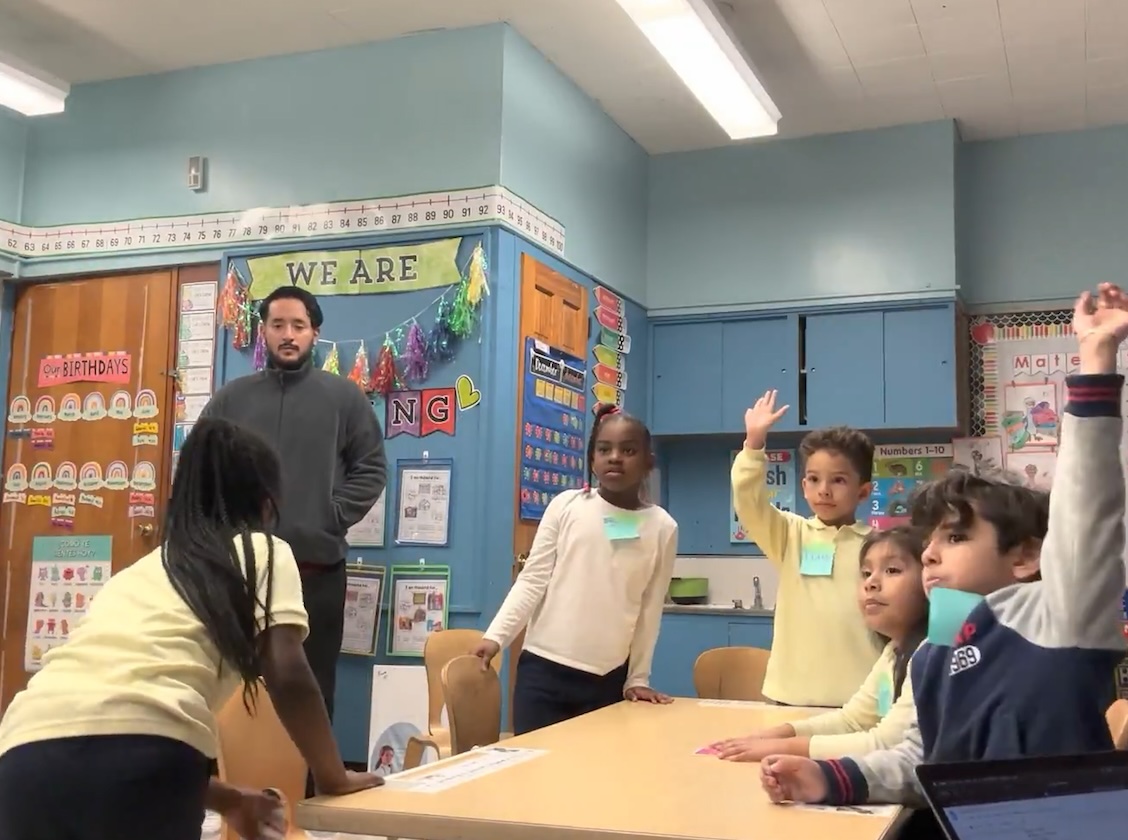

The tables were strewn with multicolored pipe cleaners, clumps of clay, construction paper, markers, feathers, scissors, tape, and other arts and crafts materials. On a Friday afternoon last June, about a dozen kids, ranging from 8 to 12 years old, filled a studio space in New York’s School of Visual Arts with noisy, exuberant chatter as they brought their brainstorms to life with marker-stained fingers. Several adults joined the creative chaos, including game designers from Mrs Wordsmith, a developer of game-based literacy products ranging from picture books to card games to video games.

This crafty gathering was a co-design session for Mrs Wordsmith’s Words of Power, a new video game built on the popular Roblox gaming platform and aimed at building vocabulary tied to social and emotional learning (SEL). Earlier that day, the kids had playtested a beta version of the game, in which players battle enemies by arming themselves with words that give specific powers linked with their definitions (e.g., the word “shock” gives players the power to electrify foes). In the subsequent co-design, kids and adults worked together to make rough prototypes for entirely new characters, weapons, powers, game features, and story arcs meant to keep kids engaged (and therefore learning) for longer. Facilitating the sessions were Azi Jamalian and her staff from The GIANT Room, a New York organization that promotes kid-centered learning innovation, and Medha Tare, senior director of research at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center.

The theory and practice of co-design have been developed for more than two decades among academics. However, the approach remains a rarity among edtech developers who too-often pump out products without any real input from their target audience. Even those companies that do seek out children’s input typically content themselves with playtesting—adults observing kids using the edtech, noting their tendencies and challenges, and asking for opinions on specific game features.

Co-design aims for much deeper insights, and it’s a cornerstone of the Cooney Center Sandbox, an initiative supported in part by the Walton Family Foundation. The GIANT Room is a partner in the Sandbox, as are two scholars who have led “KidsTeam” co-design centers that work to improve a wide variety of products for children, Mona Leigh Guha, formerly at the University of Maryland, and Jason Yip at the University of Washington. The Sandbox goal is to promote a more child-centered approach to edtech development, working with select industry partners to demonstrate what co-design actually is (and what it isn’t), how it works, and why it’s critical to making edtech that’s better for kids.

Kids Have Great Design Ideas, If You Ask Them

Co-design backers stress that partnering with children does not mean putting kids in charge of edtech creation and bringing their every whim to fruition, but rather recognizing that young people offer a unique and valuable perspective to design teams that benefit from a wide variety of expertise.

“If we do not take advantage of all that an artist or a teacher or a musician can offer the design process, then it is wrong. I believe the same can be said for children. We must understand what they have to offer the design team process,” wrote co-design pioneer Allison Druin, former professor of human-computer interaction at the University of Maryland. Druin founded the first “KidsTeam” in 1998, establishing a standing partnership of kids and adult facilitators to consult with both industry and nonprofit developers of kid-focused tech. Her sentiments are echoed by the Cooney Sandbox team, which includes experts in learning science (focused on literacy for the next three years) in addition to their co-design collaborators.

“We’re not expecting kids to know what the best way is to teach reading and writing. That’s what the research is for,” noted Tare. “Kids are experts in what they will engage in and what they find motivating.”

Engagement and motivation—both critical to learning—can be major challenges for edtech. An April 2024 article in Education Next pointed out that most apps and software tools boasting significant learning impacts in independent research, only benefit children who use the products regularly and as directed. That might seem self-evident except that the fraction of students in these trials who meet that threshold of engagement hovers around 5 percent.

“Oftentimes, as these studies show, these products work for kids who are already doing well,” said Tare. “And if that’s the case, if the technology is just helping the kid who’s at the 90th percentile get up to the 95th percentile, then what are we doing?”

One of the big ideas behind the Sandbox is that getting more input from kids early in edtech creation will lead to more engaged and motivated learning later, especially if the kids in co-design sessions represent a diverse range of learners. According to Mrs Wordsmith’s president, Brandon Cardet-Hernandez, playtesting can provide “some amazing feedback,” but “there’s something very different about co-design, because at its core you are recognizing that children have a natural creativity and an expansive point of view that, under the right conditions, can be a transformative professional development for adults and, more importantly can build sustained dialogue that can transform game development and design.”

For instance, kids playtesting Words of Power, discussed what they liked and disliked about the game and offered some overarching ideas about improving it, notably enhanced multiplayer features and an overarching storyline that would give all the word-fueled fighting some larger purpose. But in the subsequent co-design sessions, the kids weren’t simply reflecting on a product, they were imagining entirely new worlds.

One kid used clay and tiny LED lights to fashion orbs of different colors that represented elemental islands (water, fire, earth, and so forth) that players would try to conquer. Another kid crafted a dictionary that could double as a shield, part of a storyline in which monsters have stolen all the world’s words, and players set out to regain them, enhancing the power of their dictionary shields as their vocabularies grow. A third young person built an elaborate arena to facilitate multiplayer action.

The grownups in these design sessions moved from group to group, asking the kids about their efforts, building on their ideas, and offering suggestions. For instance, when one of the youngest boys showed off a blob of green clay and said he wanted players to be able to slime their enemies, adults brainstormed emotional vocabulary with him that could convey a slime power (they settled on icky).

Simply put, both playtesting and codesign seek kids’ input, but they start with very different intentions, according to Mona Leigh Guha. “With playtesters, you want some feedback on your design. You want to ask kids about your prototype, before you move on and keep designing,” she said. “Whereas, in a co-design situation, you’re looking for real collaboration. What do you think about it? Here’s what I think. What if we put these things together? We’re working together on this long term.”

Snacks and Sustained Commitment: Making Co-Design Work

Of course, an authentic and productive collaboration between kids and adults doesn’t just happen, especially when neither group is used to the idea. So, one of the first principles of co-design is building a relationship of trust and mutual respect between the adults and children in the room.

Experts like Guha and Yip recommend starting every co-design session with icebreakers, introductions, and snacks, getting everybody sitting on the floor together where they tackle a “Question of the Day” to focus participants on the design goal. For instance, because Words of Power is meant to support SEL, questions for its co-design sessions included, “When was the last time you felt very emotional?” and “What different identities do you belong to in your everyday life, and how do these identities affect the way you feel and behave?”

“Getting everybody comfortable was a big factor in making these a success,” said Denmark-based Jesper Knudsen, senior game designer at Mrs Wordsmith, who took part in the co-design sessions last June. Knudsen had worked on designing video games for a dozen years prior to joining Mrs Wordsmith in January 2024 and, like many adult co-design participants, he had not designed alongside eight-year olds and preteens before.

“It was all uncharted territory for me. Working with kids is completely different from working with adults,” he said, adding that having facilitators from the GIANT Room and the Cooney Center “really helped for someone new to hands-on co-design with children.”

Consistency and follow-through are also key trust builders in co-design, which is why KidsTeams at both the University of Maryland and the University of Washington recruit, train, and work long-term with a stable pool of kids who meet up twice a week during the school year and for a full week in summer.

That level of sustained relationship building is not possible for most edtech developers who are under pressure from investors to get products finished and on the market quickly, but Guha and Yip insist that getting kids involved in edtech design should not be an all-or-nothing proposition.

“I think Sandbox will give us a larger reach to non-academic audiences to say, here’s how you can do pieces of co-design, or you know, take what you will,” said Guha. In addition to helping facilitate sessions with Sandbox partners, she is working on a co-design toolkit for the Cooney Center, “looking at how we can make this accessible to people and make it plausible for them to take pieces of co-design and implement it in their work.”

With that said, Yip stressed that successful co-design starts with having a real commitment to making it work, because training and guidebooks aside, there’s a lot of “learning by doing.” Even with the best advice, he said, “sometimes it’s not going to work, and you’ll have to learn how to quickly shift and adapt. It’s not as frightening as it sounds, but it’s also not as easy as it sounds.”

As for Mrs Wordsmith, they are planning follow-up co-design workshops later this spring for feedback on the game changes sparked by the first sessions and to get inspiration for further refinements. The company’s initial forays into co-design left Cardet-Hernandez convinced that kids’ voices should be a part of everything they do going forward, if possible. “We’re a small company with clear values. We don’t waver on pedagogy and rigor and, in our UX and UI work, we also can’t waver on embedding young people into the creation of our world,” he said. “Moving forward, it is a central to our brand that every product on the digital and print side will be codesigned with kids,” he said. “Making edtech without the perspective of its users is like designing clothing without a fit model. You can do it, but it won’t be as great..”