Herbert P. Ginsburg, PhD, is a leading expert in early math teaching and learning. His book, Young Children’s Amazing Math, focuses on how teachers and caregivers working with very young children can promote early mathematical experiences that lay the groundwork for formal math education in kindergarten and beyond. This article shares some examples from the book, which is available at Teachers College Press.

Young children, from infancy through early childhood, develop mathematical minds. They have ideas about number, more/less, addition/subtraction, measurement, shape, space, and even infinity. Often unbeknownst to adults, this everyday math develops before or apart from formal math instruction.

Dolls and Hats

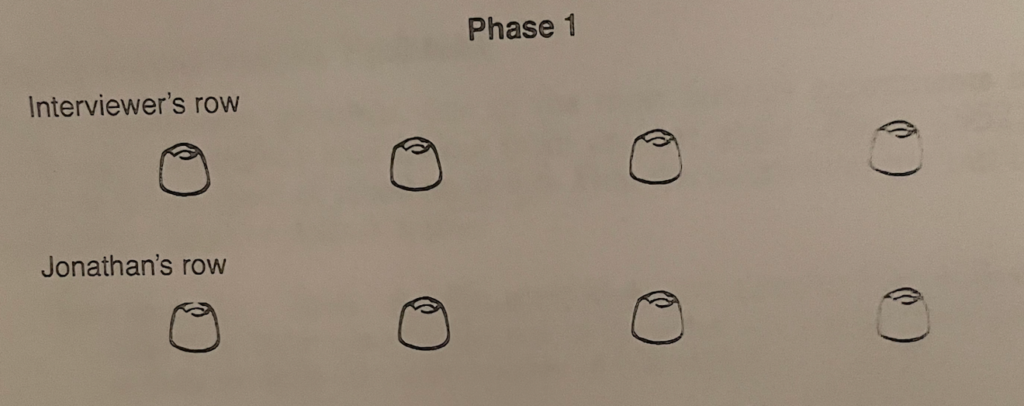

Here’s an example of how young children think about same number. I show Jonathan, 4 years 6 months, two rows of candies, one his and the other mine. The rows are identical in appearance and length.

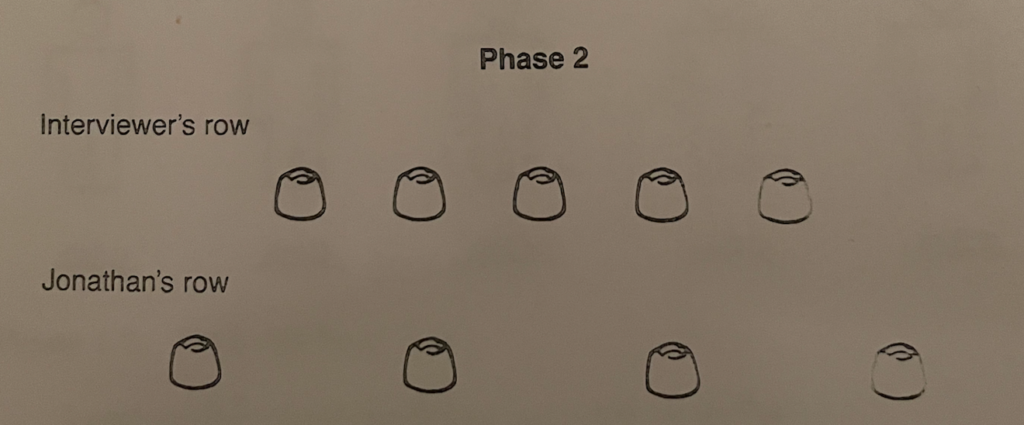

After he agrees that the rows are the same number, I say, “Now watch what I do. I move yours out and I put one here.” I added one to my row and spread his apart. “Which one do you want to eat?”

I asked this so as to increase his motivation and avoid use of words like more and same. Surely, he can comprehend instructions about eating (especially candies!). Yet in response to my question, Jonathan indicates that he would like to eat his row, the longer but less numerous!

But suppose that he now counts the objects. Would that help?

I say, “Can you count them for me?”

Jonathan counts his row correctly.

“So you have four and how many do I have?”

Jonathan answers, “One two, three, four, five.”

“So who has more?”

Jonathan quickly says, “Me.”

“You? But this one has four and this one has five.”

Jonathan says, “You put yours like that [meaning that my line is shorter] and put mine right there [meaning that it is spread it out].”

So counting does not yet help Jonathan determine same number. His number judgment is based on appearances. If the rows look the same, then they are the same number. If they look different, then they are a different number.

Amazing! Yet, although all this is typical of young children, they also have surprisingly rich mathematical ideas.

Building a Building

Watch this video of two kindergarten boys building a structure with blocks.

You will see that in the background, Alfredo had used four short cylinders (which he later calls “circle things”) and two long planks to create two structures parallel to each other. His friend comes over to join him. They make two new structures just like Alfredo’s first two. But then Kevin quickly holds up a long, thin plank between the two structures and immediately sees that it is too short. Alfredo then tries to bridge the structures with his plank. Looking carefully at how each end falls short of the mark, he asks, “How about if it don’t reach?” He immediately answers his own question by quickly moving one of the cylinders closer to the other structure. In fact, it is now in exactly the right spot for the plank to span the distance. Kevin asks, “Now you can reach it?” and Alfredo agrees that he can.

Isn’t that amazing? And this episode is only about the first 13 seconds of the 1-minute video showing that the boys employ several basic everyday math concepts:

- Distance—the plank needs to be exactly the right length to go from one cylinder to the other

- Space—the two original constructions need to be parallel

- Shape—a cylinder has a circle face, not a square one

- Location—the toy was under the platform

- Counting—a certain number of planks

- Measurement—how many are needed?

- Estimation—maybe two or maybe three

- Addition—two more planks must be placed

And finally, after some 20 minutes, the boys eventually produce this “building for cars,” roughly symmetrical, with one vertical half mirroring (reflecting) the other.

I have shown you two different kinds of amazing math. Jonathan uses an unusual and unexpected kind of thinking, prioritizing appearance over reality, that results in a strange, wrong answer. By contrast, the boys surprise us with their rich thinking, unexpected competence, and impressive result.

More Examples

My new video book (Ginsburg, 2025) involves “thinking stories” (including the two you have just seen) based mostly on 70 short videos of children’s math as it develops from about 18 months through kindergarten.

Some examples:

- Cassie learns about adding and subtracting as she plays with food on her highchair.

- Ethan uses the idea of 1-1 correspondence to guide his moral judgment.

- Maya can see numbers without counting.

- Cassie uses ideas about space and order to “read” a book.

- Natalia loves the math—including order and relative size—in the story of the three bears.

- Cassie does careful spatial engineering to prevent her construction from toppling over.

- Rachel uses mental addition to solve an imaginary problem involving rabbits and carrots.

- Cassie uses her everyday math to understand the formal math taught in school.

In addition to presenting vivid accounts of children’s amazing math, the book provides guidance on how you can nourish children’ everyday math and even prepare them for schooling. For example:

- Ask the child to talk about how they are solving a problem.

- Ask questions about their thinking.

- Provide careful hints.

- Introduce specific games and activities.

- And often leave the child alone and avoid engaging in direct instruction.

Finally, at the end, the book promotes an approach to integrating young children’s informal math with the formal mathematics taught in school. As you well know, school math unfortunately and all too often is learned in a rote, meaningless fashion, and children, parents, and teachers are often afraid of it, bored with it, and want to avoid it. This does not have to be true and this video book will show you why.

My book is designed for several audiences:

- Parents and teachers and students who want to learn about early development

- Professors of developmental and educational psychology, math education, and early childhood education

- Professional educators who do workshops with parents or teachers.

I hope that my book can help you all to appreciate and enjoy children’s amazing mathematical minds.

Ginsburg, H. P. (2025). Young Children’s Amazing Math: A Guide to Understanding and Supporting Early Learning. Teachers College Press. 1234 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027.

Herbert P. Ginsburg, Ph.D., is the Jacob H. Schiff Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. Although he holds a B.A. from Harvard University and his M.S. and Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina, his proudest academic moment was studying counting with the Count.