Global Kids, Inc. works to ensure that youth from underserved areas have the knowledge, skills, experiences and values they need to succeed in school, participate effectively in the democratic process, and achieve leadership in their communities and on the global stage. Many of the students in their programs are creating games eligible for submission into the 2016 National STEM Video Game Challenge.

Through in-school and after-school Global Kids (GK) programs, middle school and high school students examine global issues, make local connections, and create change through peer education, social action, digital media, and service-learning, while receiving intensive support from GK staff.

Games-based learning is fun, effective and powerful, but it doesn’t come without its challenges. At Global Kids we run a few different game design programs which address social and global issues. One obstacle we’ve faced across programs is immersing our youth in developing comprehensive narratives to support the mechanics, goals and other elements of their games. There’s a ton to cover with the principles of game design and computational thinking alone, how does the art of narrative storytelling fit into all of this and is it a priority?

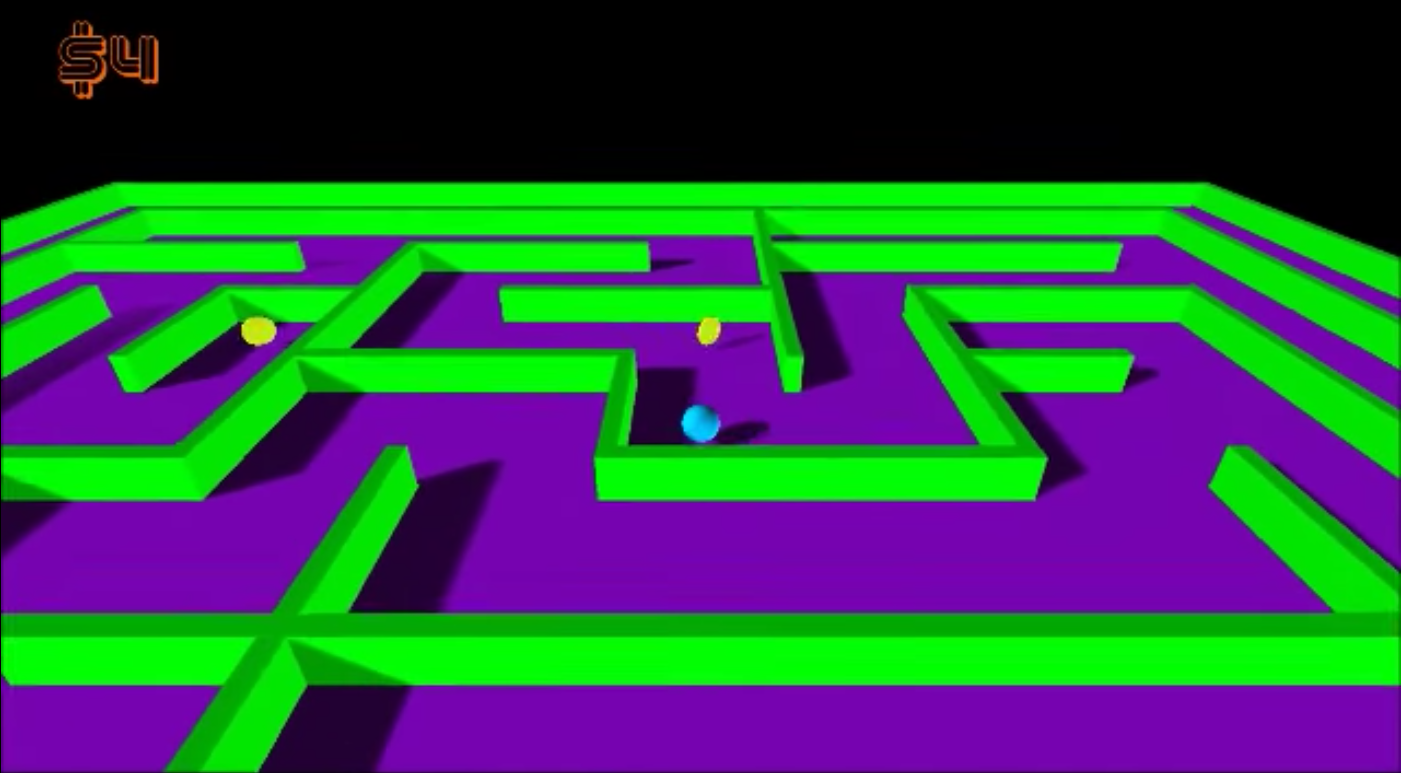

Powerful games usually have powerful narratives, which can take players on an unforgettable journey. The graphics of a maze game which depict the gradual degradation of a forest from level to level, the tools a sprite is equipped with to bounce back from attack and how the clock counts down with every life lost are all elements which support pieces of a story. It’s these small details, particularly in social impact games, which can engross players in the issues and a call to action. So the question remains, how do we teach youth to tell good stories that are then represented in games? What does that process look like?

At Global Kids, our most successful learning experiences for our youth have begun with deconstructing popular games and exposing them to the array of people and skills who create them, united by one vision. This includes the writer, artist, engineer, product designer, etc. and how they leverage character development, animation, coding and marketing to produce one comprehensive game. This can help educators reveal how games are embodied narrative, where the authors have worked together to construct a world, a series of experiences, and empathized with the game player to prepare a journey for them. Over the last six months, we’ve redesigned pieces of our curriculum to incorporate more time for creative writing, storyboarding and other exercises focused on developing compelling narratives and the vision that everyone on the team is working toward. To support the development of a common vision, like a literature or film class, we facilitate workshops on the hero’s journey before youth start coding sprites or enemies so that they have a foundation to build on. Once they have a clear understanding of their hero’s journey, youth are prepared to determine what the game character (and therefore the game player) knows, what choices the player has available to them, what abilities they have, and what will motivate and challenge them along their journey to the winning goal. We’ve discovered great tools like Storybird to help youth exercise these underused skills in an interactive, collaborative and fun way to support this framework. Equipping our students with robust storytelling skills ensures that they don’t produce games which are lost in mechanics.

For the all the games-based educators out there, what are your tools/techniques for weaving narrative into the game design process?