Last month, the Digital Media and Learning Research Hub, made possible by grants from the MacArthur Foundation, published a research report on the findings of the Connected Learning Research Network, a group led by scholars such as Mimi Ito, Sonia Livingstone, S. Craig Watkins, and Katie Salen. The Connected Learning Research Network, according to the report, is “an interdisciplinary collaboration among researchers, designers, and practitioners to advance an evidence-driven approach to learning, the design of learning environments, and educational reform that addresses contemporary problems of educational equity.”

Last month, the Digital Media and Learning Research Hub, made possible by grants from the MacArthur Foundation, published a research report on the findings of the Connected Learning Research Network, a group led by scholars such as Mimi Ito, Sonia Livingstone, S. Craig Watkins, and Katie Salen. The Connected Learning Research Network, according to the report, is “an interdisciplinary collaboration among researchers, designers, and practitioners to advance an evidence-driven approach to learning, the design of learning environments, and educational reform that addresses contemporary problems of educational equity.”

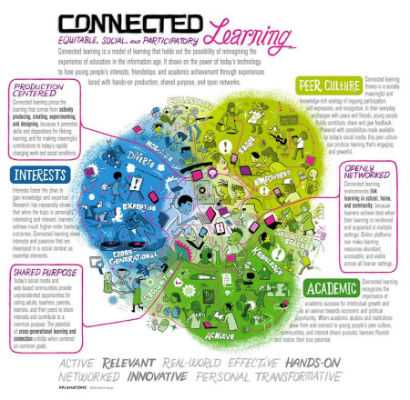

The report summarized an international investigation into the ways that new media, embedded within a strong network of social relationships, can support young people’s interest-driven learning and direct that learning towards traditional educational, economic, and political opportunities. The Connected Learning report provides a number of case studies on how learning communities develop, and how intergenerational partnerships and mentoring programs can be really powerful for young people who might otherwise have limited opportunities for participation and mentorship. The authors use the term “non-dominant youth” in the report instead of minority youth, diverse youth, or youth of color, explaining that “non-dominant explicitly calls attention to issues of power and power relations than do traditional terms to describe members of differing cultural groups” (Ito et al., p. 7).

While synthesizing a wide range of research on educational reform, the report also creates a space for ongoing conversation about the best ways to provide all children with opportunities to pursue their passions, and to do so with the support of peers, parents, and other caring adults. In the spirit of that provocation, I’d like to continue the discussion sparked by the Connected Learning report, and talk about an example of connected learning that builds upon the cases described in the report. Specifically, this example of connected learning centers on young people with disabilities, a group that adds another dimension to the discussion of “non-dominant youth.” This “group” though is loosely defined as a category as disability takes many forms and intersects with issues of economic, cultural, and institutional equity in complex ways.

Augmentative and alternative communication devices as “new media”

I came across this particular case of connected learning this past weekend when I attended the annual Assistive Technology Institute in Costa Mesa, CA. The one-day conference convened parents, teachers, therapists, and people with disabilities to discuss and learn about the latest in assistive technology services, tools, and products. “Our goal,” states the Institute’s website, “is to help enhance opportunities for learners from preschool to adult in order that they may compete and contribute in the twenty-first century.” I attended the conference as part of my ongoing research on how contemporary families incorporate new media and communication technologies into their homes, and in particular, families with children with disabilities.

“Assistive technology” (or AT for those unfamiliar with the term) is legislatively defined by the 1994 US Individuals with Disability Education Act as “any item, piece of equipment or product system whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified, or customized that is used to increase, maintain or improve functional capabilities of a child with a disability.” At the conference, AT consultants Zebreda Dunham and Martin Sweeney offered up an alternative definition of AT, as “any thing or any tool that can make life easier and more productive for people with (or without) disabilities.”

“Assistive technology” (or AT for those unfamiliar with the term) is legislatively defined by the 1994 US Individuals with Disability Education Act as “any item, piece of equipment or product system whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified, or customized that is used to increase, maintain or improve functional capabilities of a child with a disability.” At the conference, AT consultants Zebreda Dunham and Martin Sweeney offered up an alternative definition of AT, as “any thing or any tool that can make life easier and more productive for people with (or without) disabilities.”

One kind of AT is an augmentative and alternative communication (or AAC) device. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association defines AAC as “all forms of communication (other than oral speech) that are used to express thoughts, needs, wants, and ideas.” There are many different types of AAC and many types of AAC users. Some AAC relies on the users’ body to communicate (for example, sign language), while other AAC requires the use of tools or technological equipment in addition to the users’ body. These “aided” forms of AAC can range from “no-tech” items such as paper and pencil to “high-tech” mobile devices that produce voice output. The price range then for AAC can be mere cents or tens of thousands of dollars. Some high-tech AAC devices are essentially portable computers with the sole purpose of providing AAC, while other AAC devices have other functions too (for example, iPads loaded with AAC apps).

People who use AAC need it because they have severe speech or language problems, and this includes people across the lifespan. Adults and children may use AAC due to a developmental disability (e.g. autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy), an injury or illness that impacts their communication (e.g. stroke), or a progressive neurological condition (e.g. multiple sclerosis). People who use AAC need different ways besides or in addition to oral speech to express themselves.

One way that AAC use is supported is through AAC user groups, which are meetings for people who use high-tech AAC devices to use them among one another. Research indicates that AAC users can often feel isolated from others who communicate in the same manner, and that this lack of opportunity contributes along with many other factors to inconsistent AAC use and less social, cultural, and civic participation. AAC users, young and old, tend to know few other AAC users. For example, a child might be the only AAC user in his or her entire school, which has implications for their sense of belonging.

Disability and diversifying “connected learning”

Getting back to the issue of connected learning, one of the panels that I sat in on at the conference was entitled “The Mentoring Program: Adult AAC Users Mentoring Child AAC Users.” Kathleen Rausch M.S. CCC-SLP, a speech-language pathologist at the Assistive Technology Exchange Center at Goodwill Industries of Orange County, CA, and Kim Vuong, an AAC user and mentoring program participant, presented the results of a recent pilot program: an AAC group that brought together adults and children who use high-tech AAC devices.

Intergenerational AAC groups are novel; such groups typically consist of either adult or children only for a number of reasons including topics of conversation and levels of parental involvement. The mentoring program presented paired adults and children who use the same AAC device to communicate. This pairing is important since AAC devices and systems can vary greatly.

Rausch and Vuong reported that the program provided adults and children in the group with opportunities for increased social engagement. While the young AAC users enhanced their communication capabilities, the older AAC users gained mentoring skills. Rausch and Vuong’s work, like the Connected Learning research, was about digital media and adults mentoring children in the pursuit of a common interest. Work with children with special needs is notably underdeveloped within the growing body of Digital Media and Learning Hub research. In a recent article in the International Journal of Learning and Media, Peppler and Warschauer (2012) point out that little attention has been paid to how children with disabilities, too often poorly served by educational systems, are marginalized from research on interest-driven learning, out-of-school learning, and learning with digital media.

This gap in the research not only omits the work of practitioners like Rausch and Vuong from the conversation on digital media and learning, but may actually be to the detriment of those generally interested in studying connected learning. For example, in their presentation Rausch and Vuong discussed takeaways that while specific to a particular form of mentorship under the specific conditions of the AAC users group are highly relevant and generalizable to connected learning as a model:

- Perspective taking: The child and adult AAC users in the mentoring group, particularly those in wheelchairs, encountered differences in seat elevation that made one conversation partner unable to view the screen of the other person’s communication device. It can be helpful for a conversation partner not only to hear the speech output coming from an AAC device, but also to see the visual symbols on the screen as well. The interpersonal skill of “perspective taking” in this sense encompasses both the physical and the metaphorical. In order for the adults and children in the AAC users group to engage in connected learning, they had to find common ground and learn how to share space in ways that are similar but also different from the examples of intergenerational perspective taking in the Connected Learning report.

- Adults are learners, too: Even proficient adult AAC users in the group did not always know how best to initiate and sustain communication exchanges with child AAC users. While children and their parents gained more confidence about AAC through the program, the adults gained experience in mentoring and enjoyed leading activities with the children. More generally, adults engaged in connected learning might be experts in certain skills or knowledgeable in particular areas, but learning to give appropriate help and feedback is part of adults’ learning process as well.

- Communities of practice: The AAC users group provided children with unique opportunities to shape their identities. The children had role models in and a shared purpose with the adult AAC users, role models that they can draw on to construct their sense of selves, both now and in the future. It cannot be stressed how few the opportunities are for young AAC users to belong to such communities of expertise.

Conclusion

Young AAC users have complex communication needs, and thus need multiple points of entry and outreach to enter connected learning environments. While advances in digital and mobile media have enabled a wider range of possibilities for meaningful communication among young people who use high-tech AAC device, these possibilities also exist among various institutional, educational, cultural, economic, and social constraints. As the Connected Learning report notes, “Without a broader vision of social change […], new technologies will only serve to reinforce existing institutional goals and forms of social inequity” (Ito et al., p. 41). As I’ve illustrated with my brief glimpse into the research presented at the Assistive Technology Institute on intergenerational AAC users groups, without a broader vision of connected learning itself, the current research agenda on new technologies will similarly isolate young people with disabilities from educational, economic, and political opportunities and prevent them from also competing and contributing in the twenty-first century and beyond.

References

Dunham, Zebreda, Martin Sweeney. Zen & the Art of No-Tech Assistive Technology. 2013. Presented at the Ninth Annual Assistive Technology Institute, Costa Mesa, CA. http://www.zebredamakesitwork.com/trainings/

Ito, Mizuko, Kris Gutiérrez, Sonia Livingstone, Bill Penuel, Jean Rhodes, Katie Salen, Juliet Schor, Julian Sefton-Green, S. Craig Watkins. 2013. Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Peppler, Kylie A., Mark Warschauer. Uncovering Literacies, Disrupting Stereotypes: Examining the (Dis)Abilities of a Child Learning to Computer Program and Read. 2012. International Journal of Learning and Media, 3(3): 15-41.