In Amazon lore, CEO Jeff Bezos reportedly once said, “I very frequently get the question: What’s going to change in the next 10 years…I almost never get the question what’s not going to change…and I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two—because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time.”

Usually, I’m called on to speak about change in the world of children’s media, given that I work for a trend research consultancy. Recently, though, I’ve found myself thinking about the above quote.

In the kids’ media industry, it’s critical to understand both what changes and what never does —specifically children’s development. Jean Piaget and Maria Montessori, among others, recognized that young people across time and place need to pass through the same cognitive, physical, social and emotional stages in order to navigate childhood successfully. What varies radically, over time and across cultures, is the context in which kids grow and learn.

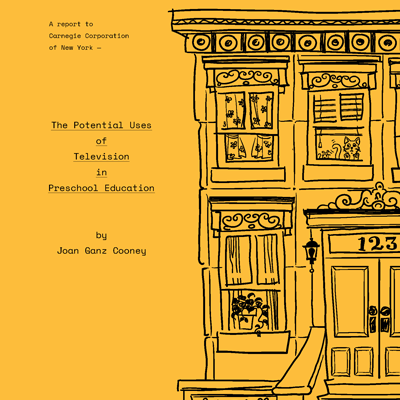

That’s why I went back and re-read Joan Ganz Cooney’s seminal 1966 report to the Carnegie Corporation of New York, “The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education.” The report paved the way for development of Sesame Street and, by extension, the global tsunami of preschool TV, websites, apps, games and products that has followed in its wake.

Imagine the world into which Sesame Street was born. Not only was there no digital media; the number of TV channels could be counted on one hand. There was no Public Broadcasting Service—only its precursor, National Educational Television.

This makes Cooney’s vision that much more prescient. Throughout the document are quotes that could be written about today’s omni-platform anything, anytime, anywhere children’s media environment. Here are five that struck me:

The Myth of Attention

Another myth that has been handed down over the years has to do with the young child’s attention span…Whether or not many hours of viewing television is good for children, we do know that they are capable of long periods of absorption in all kinds of television programs…a young child will remain with a given task or project if it interests him, for surprisingly long periods of time.

This remains one of the most persistent fictions regarding children and media, even more prevalent and pernicious since the advent of streaming platforms. Adults see young people consuming short videos on YouTube and conclude that today’s kids have diminished capacity to focus.

One need only watch a toddler entranced by Frozen or a tween immersed in a Minecraft build to know that—as Cooney suggested—children have enormous focus for content that engages their curiosity, intellect or emotions.

For the U.S. at least, YouTube was most kids’ first opportunity for short-form content, given the over-the-air reliance on 30- and 60-minute programming. It was a novelty to see short stories. It also opened the door for today’s video world where stories are allowed to find their right length. A series can be any number of episodes, each of any duration.

Collections of short items – as Sesame Street was in its early days – can actually enhance attention. Last year, FX Networks CEO John Landgraf talked to NPR about FOMO (fear of missing out) and said, “Anytime you choose something you’re also un-choosing something else.” In a crowded media environment, a child may remain attentive through a series of shorts in hope of catching a favorite bit of content.

Evolution Never Stops

We cannot wait for the right answers…rather we should look upon the first year of broadcasting for preschoolers in the nature of an inquiry. There is no substitute for trying it, and evaluating its effects, if we wish to know whether television can be a valuable tool for promoting intellectual and cultural growth in our preschool population.

Media skeptics often call today’s world of media and technology a “vast uncontrolled experiment” on children. Cooney understood from the start, though, that any effort to educate, inspire, inform—indeed, to entertain—children via television would necessarily be experimental and metamorphic.

Perhaps the wisest choice Cooney made was to call her organization the “Children’s Television Workshop.” The name makes clear that there is never an end point. Sesame Street has embodied that idea both in the US show’s evolving structure and goals, and in its global adaptations and purpose, to the present day’s refugee outreach.

The same is broadly true of children’s media and technology. We’ve been in a period of rapid change since the advent of the smartphone. Both creators and kids have been exploring in real time the possibilities and limitations of emerging devices and content. Kids have driven a lot of the innovation; the smartphone and tablet weren’t designed for children, but they quickly made them their own, often finding ways to use them that developers hadn’t anticipated. The creative community has had to adapt to this vast, uncontrolled experiment in a productive give-and-take between designer and user.

Fortunately, networked digital media is easy to update. Once Sesame Street episodes were committed to videotape, that was the final version. With websites, games, apps, even connected toys, release is just the beginning, with regular extensions and updates based on analysis of users’ experiences.

The Interactivity Foundation

The children in the viewing audience at home would be encouraged to correct him when he was wrong or particularly simpleminded, and they would have to be attentive in order to do so.

Malcolm Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point profiled how Blue’s Clues learned from the processes and structures of Sesame Street. Joan Ganz Cooney actually predicted its interactive format 30 years before, suggesting segments in which the viewing audience would be invited to talk to the screen, and would often be more “clued-in” than the characters in the show.

Blue’s Clues simulated communication. It debuted into a truly-interactive world of game consoles, CD-ROMs and software. The natural progression of technology since has been toward more personal, portable and participatory.

Beyond such simple interaction, Cooney anticipated the value of heighten attentiveness and engagement. She suggested that programs proceed from simple concepts to more complex concepts and that it would be possible for a single segment within a program to proceed from simple to more complex. Television used repetition of segments or shows to help children grasp the full depth of the content; digital media enabled each user to have an appropriately-leveled experience.

It Takes a Village

I will outline briefly some of the ways television could be used to entertain and teach young children, but it is well to remember that any group of creative people brought together to produce such a series would devise many, many more.

Fifteen years after Sesame Street debuted, I worked in programming at the Public Broadcasting Service. At the time, I had local programming executives tell me (literally), “We don’t need any more children’s programming; we have Sesame and Mister Rogers.”

This was at the beginning of the cable era, when Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network, Disney Channel and others proved that the young audience is not a monolith. More accurately, it’s a Rubik’s Cube of developmental abilities and needs, interests, passions and preferences. Every twist reveals a different subset of the children’s audience seeking different genres, stories and characters. Kids, too, turn to different devices and platforms depending on where they are and what they feel they need, so diversity of content is not just a TV concern.

(Public broadcasters have absolutely come around to the understanding that their youngest audiences are diverse, and offer a fantastic array of learning-driven content across platforms.)

The advent of YouTube transformed the multi-channel universe into the one-channel universe: #ChannelMe. Some believe we’ve gone too far—there is so much content that young people struggle to discover what they want (in Dubit’s Trends research, more than 60% of kids worldwide tell us they’re frustrated by this). Still, it’s important to focus on what Cooney implies in her quote: The world has a wealth of storytellers from unique cultures, traditions, and approaches, and children deserve the same scope and depth of content that we adults expect.

Since the advent of television in the United States, children rely more and more on it for their entertainment, and less and less on their own imagination and resources.

Not all of the quotes envisioned a positive media universe. Cooney was conflicted about contributing to the growing role of TV in children’s lives. With proliferation of devices, platforms and content, the time children devote to media engagement is now multiple times what it was in 1969.

Note that I don’t use the term “screen time,” though. When Sesame Street debuted, there was one screen in the home, delivering limited one-way entertainment and information. Today, with screen-based (and no-screen) devices used to communicate, socialize, explore, learn, read, listen, play, watch, create and more, a stopwatch is a useless tool for evaluating engagement. There’s a long tradition of angst over how the next generation’s ways differ from our own—starting with Plato’s concern that writing would ruin the oral tradition. We’re still discovering whether children’s omnivorous media use is harmful to imagination and resourcefulness, or simply a different and still-emerging way of engaging that we don’t yet comprehend.

Fortunately, this is what the Joan Ganz Cooney Center was founded to explore. So, 54 years after Cooney’s seminal white paper, her influence continues to shape the future.

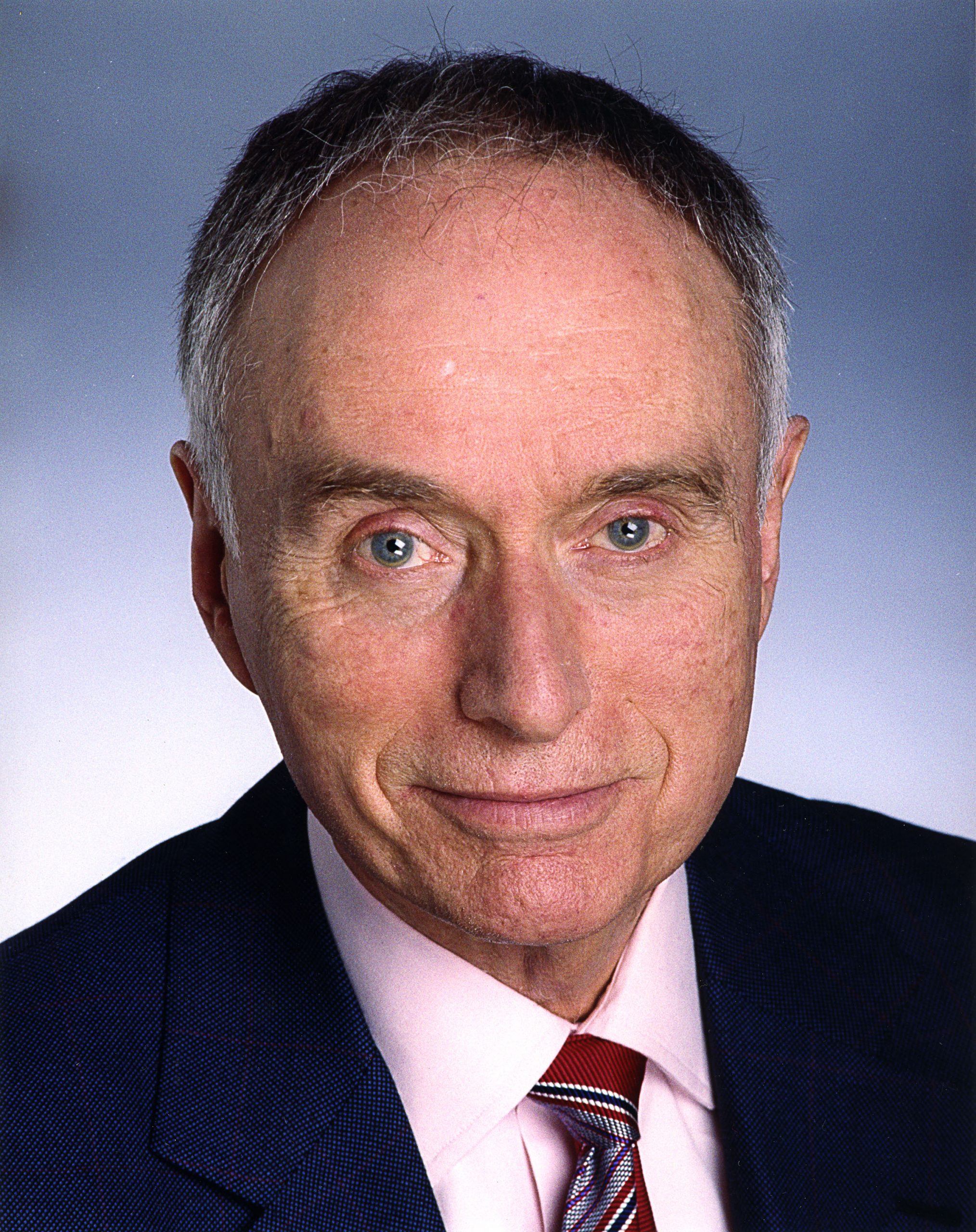

David Kleeman is a strategist, analyst, author and speaker who leads the children’s media industry in developing sustainable, kid-friendly solutions for more than 30 years. He began this work as president of the American Center for Children and Media and is now Senior Vice President of Global Trends for Dubit, a strategy/research consultancy and digital studio based in Leeds, England.

David Kleeman is a strategist, analyst, author and speaker who leads the children’s media industry in developing sustainable, kid-friendly solutions for more than 30 years. He began this work as president of the American Center for Children and Media and is now Senior Vice President of Global Trends for Dubit, a strategy/research consultancy and digital studio based in Leeds, England.

This article originally appeared on Kidscreen.com, [c] Brunico Communications Ltd. Reprinted with permission.

![]()