When schools across the U.S. shut their doors in March 2020, families were confronted with the reality that our educational systems were not designed for remote instruction. Lack of access to the internet or devices, variation in teacher preparation, working parents, and uncertainty of how to best engage learners presented a range of obstacles. Adapting to the demands of learning from home required significant flexibility and resilience on the part of families, and the ways in which they were able to adapt offer us an opportunity to learn how we can better support students, families, and schools during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our team learned directly from 109 diverse families with K-5 children around the U.S. during the initial months of adapting to distance learning. Caregivers, including parents and a few grandparents and adult siblings, provided daily diary entries via dscout, a remote research platform. These entries allowed us to not only see how learning looked at home for a range of unique families, but also to gain insights from caregivers about the challenges they faced in this transition period and their unique strategies for addressing them. For more on our methods, please see Learning Together: Researchers and Families as Partners During COVID-19.

When asked about challenges they were facing, caregivers described a diverse range of issues associated with their new roles as co-facilitators of learning.

- 64% described how stepping into roles usually played by teachers was tough. Many found it difficult to find the time to help their child with their schoolwork during the day due to other demands on their time such as work and family care. When they did find time, many were unsure about their ability to teach related to both content knowledge and pedagogy. Sentiments like “I’m not a teacher” were voiced frequently, and were especially common when it came to helping with early reading and Common Core math.

- 59% expressed concerns about their child’s school learning and engagement. Caregivers frequently described how difficult it was for their children to focus on their school activities and stay motivated to complete assignments. Various distractions around the house, such as toys, snacks, siblings, and trouble with technology interfered with completing school assignments from home as well as the missing routines that kept their children focused in school. Some caregivers had questions about how much their child was learning and worried about their child falling behind, not so much because there was any direct evidence but more related to their new responsibilities in relation to their child’s academic learning.

- 51% worried about their children’s social, emotional, and physical wellbeing. Over half of caregivers shared how much their children missed their friends, classmates, and teachers and some were concerned about the development of social skills during this period of relative isolation. Several shared concerns about their child’s anxiety or frustration, often related to schoolwork, and their physical wellbeing, including too much screen time and lack of physical activity.

Importantly, we found that not all families had equal access to technology-supported learning resources. Families living on less income reported lower rates of synchronous connections to class lessons, access to teacher-created videos, and individualized communication with the teacher. They also had fewer technological tools at home.

Nevertheless, through deeper descriptions of the daily learning moments happening at home and reflections about their family’s experiences with remote learning as the 2019-20 school year came to a close, it was clear that for most families these challenges provided opportunity for creative adaptation. Families were not only together in their struggles but also in their willingness to adapt and innovate to address learning and social-emotional challenges. Parents were able to complement what schools offered and often tapped into child interest areas and personalized learning for their kids in a way that teachers could not during remote learning.

-

A mom used Play-doh to review fractions with her first grader. Illustration: Stanford GSE Building on teachers’ successful strategies. To overcome lack of child engagement and time crunches on teaching, we saw parents like Cara listen in on online teaching moments and use that knowledge to integrate learning into play. After seeing an effective lesson, Cara extended her first grader’s Play-Doh playtime to help her review fractions, “[my daughter] said it was so mind-blowing, and I think that she didn’t only learn just math, she was also learning creatively because she was applying her artistic skills”.

- Leveraging household resources and activities. Parents often used their own knowledge, interests, and household resources (including family members) to make academic concepts meaningful and understandable. When her daughters were struggling to understand measurements in online math classes, Arielle baked a cake with them and had them handle measuring the ingredients. Jadon included his son in his own health journey during quarantine by teaching him about nutrition. Other families taught their kids how to do yard work or included them in gardening as a way to get exercise and learn new skills. These activities often also provided physical, social, and emotional supports as siblings and parents worked together.

- Connecting to outside and hands-on STEM. Multiple families found ways to extend classroom science curricula through at-home activities. Some were extensions of school assignments while others were totally homegrown. Jade taught her grandson about plants by involving him in her backyard garden. Polly and Hao bought their children science kits to work with at home after seeing their interest in online science class. Jake helped his son build a realistic aqueduct in their backyard after reading about those in ancient Rome. Lucy described a “puddle walk” on a rainy day that she used as an opportunity to teach her first and second graders about the water cycle.

- Brokering new opportunities for learning and socializing. While many caregivers worry that digital interaction can’t replace the in-person socializing their kids would have done in school, many worked to create the best social opportunities possible. For example, setting up Minecraft missions for kids to complete with their friends, creating a collage of photos of memories with friends before the pandemic, or arranging for a young reader to lead storytime for their younger cousins over Facetime. They also searched online for potential learning activities and resources for their children, such as digital books and personalized learning platforms that would align with their interests and support engagement.

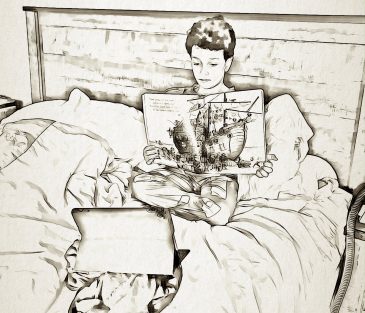

- Making sense of the moment through reading together. Reading and listening to stories was an engaging activity for many of the children and some caregivers took the opportunity to connect literacy-rich activities to deeper issues. Lucy used nightly reading time to share the Little House in the Prairie historical fiction series with her two daughters, offering an opportunity for developing a shared emotional perspective about going through quarantine together, making connections to the need to handle isolation and work with resources at hand. These read-aloud sessions also led to online explorations of the geography described in the books, YouTube videos of oxen plowing fields, and inspired baking bread and making butter at home. Esther joined in on an optional school social studies assignment that allowed her and her 5th-grade daughter to read online about the histories of the towns they were each born in, giving Esther an opportunity to teach about her “roots” and her daughter a chance to ask her questions about specific places described or pictured. On other occasions, they discussed Bible passages to put the pandemic in a personally relevant historical and spiritual context.

These everyday adaptations not only supported children’s engagement in learning, but led to some benefits. Almost all caregivers reported that their children were able to keep up academically and many said they went beyond what was expected. The majority of caregivers reported new insights about what and how their children were learning. More than a third reported feeling closer to their child’s teacher.

As we prepare for a future that includes new forms of remote and hybrid learning, it is essential to recognize the implicit collaboration between teachers and caregivers in supporting learning and the need for new ways to better support that teamwork moving forward. We need to ensure that these types of relational supports are happening for all families and that teacher and caregivers have access to the devices, digital content, and broadband access that will support sustained learning. These are minimum requirements. There is also significant opportunity for innovation—we need novel forms of parent-teacher collaboration organized to share insights about learning, supports for teachers to recognize families as equal learning partners, assessments that are useful for families, and better practices for supporting learners’ interest, curiosity, joy and engagement in meaningful learning over the long term.

All authors have contributed equally to this writing.

Brigid Barron is a Professor of Education and the Learning Sciences at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education. Her research investigates the dynamics of learning ecologies with a focus on how digital technologies can serve as catalysts for collaborative learning within and across home, school, and community settings.

Susie Garcia is an undergraduate at Stanford University pursuing a major in Economics with a concentration in Development and a minor in Philosophy.

Caitlin K. Martin is a senior researcher with Barron’s lab at Stanford University and is an independent research and evaluation consultant focusing on out-of-school learning and data visualization.

Rose K. Pozos is a PhD candidate at Stanford University in the Learning Sciences and Technology Design program, where she studies everyday family learning.