When I was a fourth-grade teacher, a minor scandal broke out when a student—who had proudly shared his private password with several friends—logged into our school library platform to find that all of his contacts and corresponding book recommendations had been deleted. This wasn’t due to a system glitch or the accidental click of a button—instead, a nascent classroom hacker had used that freely shared password to play a practical joke on her classmate.

Looking back, this incident might have served as a powerful teachable moment about some of the practical and ethical considerations associated with going online, though I didn’t consider it at the time. Like many elementary school teachers, I was already overwhelmed by my other core teaching responsibilities and uncertain about how to navigate this emerging domain of children’s digital privacy and security education.

In 2021, I was happy to have the opportunity to revisit this subject when I joined the Security & Privacy Education 4 Kids (SPE4K) Project as a PhD student researcher, where I worked with Drs. Jessica Vitak and Tamara Clegg from the University of Maryland and Dr. Marshini Chetty from the University of Chicago to develop elementary classroom privacy and security learning resources in collaboration with local Maryland and Chicago public school teachers. Through this work, I came to better understand the importance of introducing privacy and security concepts to young children to prepare them for dilemmas they will face as they grow older and as technology continues to evolve.

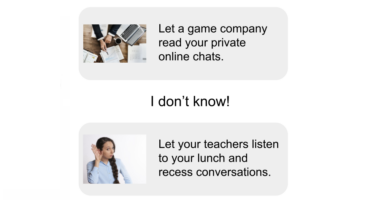

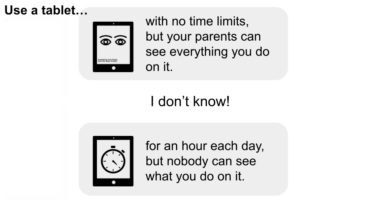

One classroom activity our team has found promising in helping children grapple with the nuances of everyday privacy and security challenges is hypothetical scenarios, like those posed in the game, ‘Would You Rather’. For example, a teacher might ask their class:

- Would you rather give a stranger your house key, or let a stranger read your diary?

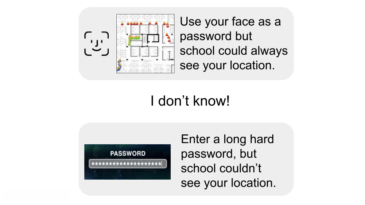

- Would you rather use your face as a password, but school could always see your location, or enter a long hard password, but school couldn’t see your location?

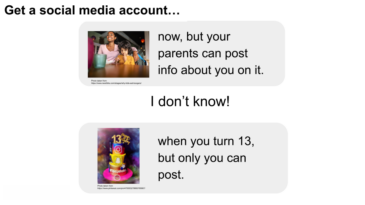

- Would you rather get a social media account now, but your parents could post about you on it, or wait until you’re thirteen, but only you could post on it?

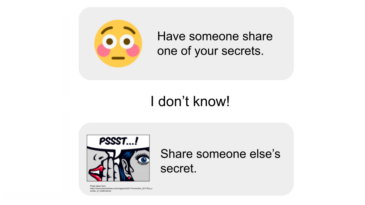

Like most privacy- and security-related decisions, these hypothetical dilemmas lack clear “right” or “wrong” answers, rendering them useful conversation starters to help children examine how privacy and security concerns surface in their everyday lives and to think critically about their priorities with respect to these topics. Additionally, the playful – and sometimes outlandish – nature of these dilemmas provides opportunities for children to think about privacy and security beyond the constraints of their everyday lives, in which parent and teacher supervision often limits or dictates what choices children can, and do, make.

Our Research Approach

We developed six privacy and security ‘Would You Rather’ scenarios and shared them with 13 elementary teachers to gain insight into the feasibility and appeal of using this type of learning activity in the classroom. We also ran the activity with three intergenerational co-design teams to examine how children evaluated the pros and cons of the scenarios. In these sessions, children and adult participants cast their votes on a given scenario before engaging in a whole-group discussion about the rationales behind their choices and their relative advantages and disadvantages.

Privacy & Security Would-you-Rather Scenarios

Our Findings

In addition to being perceived by teachers as relatively easy to implement and adapt to their students’ interests and learning needs, we found that this ‘Would You Rather’ activity was useful in eliciting children’s priorities, mental models, and context-based considerations when evaluating hypothetical privacy and security threats. We observed that children frequently attended to the following criteria:

- The potential for embarrassment. In evaluating the prospect of personal embarrassment, children considered the nature of the exposed information (e.g., “super duper secrets” versus “not very embarrassing” secrets) and the extent to which their personal control over this information might be compromised. For example, one 7-year-old said she was “worried about somebody posting something that I don’t want posted, like a picture of me with the worst hair style, but they think it’s pretty.”

- Implications for personal relationships. Children often reflected on how their privacy and security missteps could negatively impact their friends and family. An 11-year-old shared her concern that her dad’s work information could get hacked if she wasn’t careful when using his computer, while a 9-year-old worried a game company might “hack into your device and send a message in your private chat to say, ‘I’m not your friend anymore, go away.’”

- Strategies for ‘winning’ the game. Many children capitalized upon loopholes afforded by the playful and hypothetical nature of the dilemmas we posed. For example, a 10-year-old explained how he could “cheat the system” by simply deleting anything his parents posted about him on social media, demonstrating his desire to outsmart those who might pose a risk to his privacy as well as the constraints of the game.

- Established privacy and security norms and mental models. Children also frequently referenced the rules (or lack thereof) to which they were accustomed in their everyday home and school environments. Most indicated they were comfortable with the rules put in place for them by adults, but suspicious of the “weird and sketchy stuff” a company might do with their information.

Our Recommendations for Educators

We offer the following recommendations for using hypothetical privacy and security dilemmas in the classroom and beyond.

- Build on children’s unique experiences, values, beliefs, and interests. Rather than looking for gaps in children’s knowledge, this discussion-based activity can serve as a valuable informal assessment to help educators build upon students’ assets and prior knowledge. This can, in turn, inform the refinement and development of additional classroom-specific privacy and security dilemmas.

- Follow children’s lead. Children’s reinvention of the confines of these hypothetical dilemmas can provide opportunities for them to engage in the types of flexible thinking and attention to context demanded of real world privacy- and security-related decision-making. Accordingly, we recommend educators focus on helping children accept and navigate this ambiguity, rather than imposing ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ answers, as is characteristic of more punitive privacy and security learning approaches.

- Don’t just facilitate–participate! While several of the co-facilitators in our ‘Would You Rather’ sessions were privacy and security scholars, this level of expertise is not required to engage in these types of discussions with children. By modeling their thought processes as they work through various personal concerns and priorities, educators can authentically communicate the nuanced thinking required—of, not only children, but also adults—when making privacy and security decisions.

Check out our full paper here.

Blinder, E., Chetty, M., Vitak, J., Torok, Z., Fessehazion, S., Yip, J., Fails, J.A., Bonsignore, E., & Clegg, T. (2024). Discussing privacy and security tradeoffs with children using hypothetical ‘Would You Rather’ scenarios. Proceedings of the ACM: HCI, 8, CSCW1.

Elana Blinder is a doctoral candidate at UMD’s College of Information Studies, with a focus on Child-Computer Interaction and the Learning Sciences. Her current research explores how reflection, supported by tools and processes co-designed with children, can influence children’s design learning and identity development.