Two distinct mainstream narratives about the Internet really stand out. The first worries that too much digital media will erode our collective moral fiber. The second hails the Internet as a great social equalizer. Both of these narratives end up looking pretty absurd when considered alongside a new study from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Some folks worry that civilization as we know it will crumble due to changes in the etiquette of communication and relationships; some even argue that screens are a pediatric health concern. I would argue that beneath the obsession about “too much screen time” lies a resistance to change. In fact, each era’s technological innovations are accompanied by a similar moral panic: the fear of losing our habitual ways of being. Each generation, parents struggle to maintain their well-worn identity narratives within the context of a life lived with new tools—and then project that anxiety onto their children.

But parents often forget that what is “comfortable” is not necessarily the same as what is “right.” And they may not notice that they are attempting to hold their children accountable to developmental ideals that are only relevant within obsolete contexts.

Now take that fear of overexposure and compare it to the notion that the Internet is civilization’s great equalizer. Consider how it gets caught up with our familiar love of the underdog story.

For example, if you listen carefully, you can hear a celebration of web-equity in the myth of the heroic YouTuber who becomes a superstar, circumventing the big media conglomerates that hold a monopoly on our entertainment industry. Read between the lines and you’ll find it in each aspirational rags-to-riches news features chronicling the making of an Etsy or eBay fortune. It’s lurking in the promise that with fiber-optic cable, an Intel chip, and clear understanding of computer science, you might have mined your way to wealth in the early days of the BitCoin gold rush.

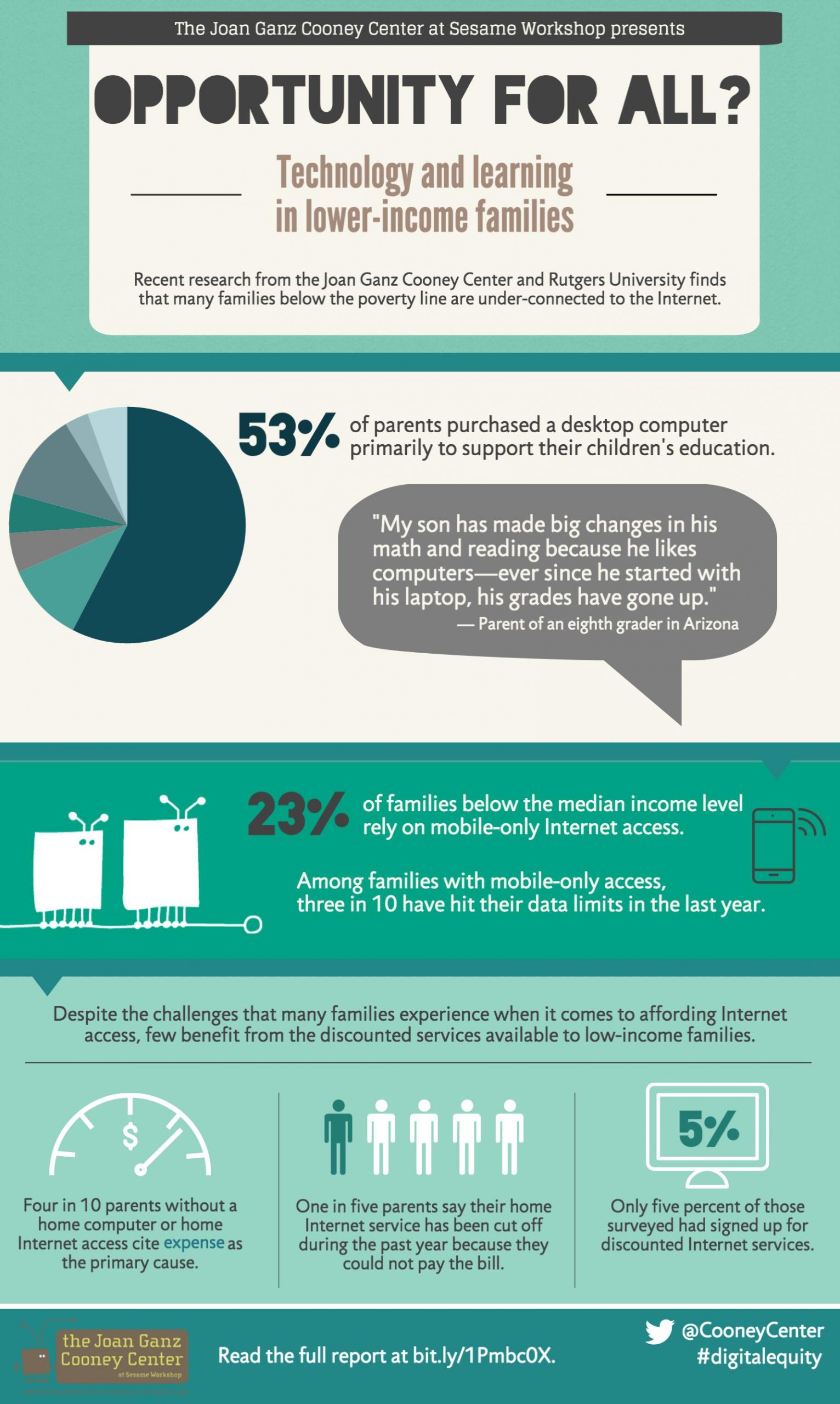

It turns out that both of these narratives—which are concerned with issues of exposure, equity and access—are way out of whack. When you look at Victoria Rideout’s and Vikki Katz’s new report, Opportunity for All: Technology and Learning in Lower Income Families, it is clear that a huge chunk of the U.S. population is under-connected. That means they really can’t be over-exposed, nor can they take advantage of the opportunities that saturate a supposedly equitable web-economy.

It turns out that both of these narratives—which are concerned with issues of exposure, equity and access—are way out of whack. When you look at Victoria Rideout’s and Vikki Katz’s new report, Opportunity for All: Technology and Learning in Lower Income Families, it is clear that a huge chunk of the U.S. population is under-connected. That means they really can’t be over-exposed, nor can they take advantage of the opportunities that saturate a supposedly equitable web-economy.

Consider the notion that most families, regardless of income level, have some form of Internet connection. But many are limited to mobile-only access or have inconsistent connections. According to the report, 23% of American families whose income falls below the median level, and 33% below the poverty level, rely on mobile-only Internet access that’s not dependable. A fast desktop or laptop computer with a good broadband connection is just not financially feasible for many Americans, so they’re stuck with Internet that’s too slow (52%), shared by too many family members (26%), cut off for lack of payment (20%), and/or reached the data limit in the last year (29%).

Despite admirable efforts (such as President Obama’s “ConnectHome” initiative) to provide more equitable access to broadband, discounted Internet programs like these are still reaching very few people. Only 6% of eligible families are taking advantage of such resources. And the data gets even more disheartening when broken down by race and ethnicity. “Families headed by Hispanic immigrants are less connected than other low- and moderate-income families. One in ten (10%) immigrant Hispanic families have no Internet access at all, compared with 7% U.S.-born Hispanics, 5% of Whites, 1% of Blacks.”

Use of the World Wide Web, it seems, remains far from equitable. This means it is probably a stretch to assume that our society, on average, is over-exposed. And it is even more absurd to imagine the web as if it were some sort of equalizer. Let’s be crystal clear and say that again: the human race as a whole is not on its way to becoming a bunch of anti-social cyborgs. And the way we are implementing networked digital technologies is not helping to create an even playing field. Instead, it is reinforcing the disparate socio-economic lines along which opportunity, information-exposure and cultural alienation has been distributed for centuries.

I suspect that when most of us think about what it means to be under-connected, all of the news media, information, and data that we encounter on a daily basis comes immediately to mind. When studies like Rideout’s and Katz’s highlight the divide between the under-connected and the adequately-connected, we all acknowledge how it will inevitably lead to a widening skills gap—particularly when it comes to computer skills like writing code and using sophisticated business software. We also probably recognize the advantage that some students enjoy in more traditional academic subjects just because they have the tools to easily complete their homework without needing to visit a public library or a coffee shop with free Wi-Fi.

But that’s not the whole issue. Parents of adequately-connected computer-savvy children should also consider what is happening when their kids spend interacting with PC games like Minecraft and tablet games like Little Alchemy. Recognize that while your children are playing, they are also learning to be comfortable in a connected world. They’re developing the confidence to easily operate and experiment with digital tools. They are experientially applying higher order thinking skills within virtual environments. And therefore, they are also becoming acclimated to subtle social cues and nuanced behaviors that will ultimately make them easily identifiable as the privileged, the cultured, and the elite. They’re procuring habits-of-mind that will eventually draw the line between the insiders and the alienated.

At the end of the day, remember that child development and education are both always about how young people learn to make use of language, knowledge, and academic content within the context of lived experience. Although we often think of “context” as if it were some sort of abstract cultural or historical zeitgeist, the reality is much simpler. For humans, context is all about how we use a particular sets of tools to intellectually, emotionally, economically and materially fabricate our world. Lacking exposure to those tools is like being locked in closest for most of your childhood.

If we can’t figure out a way to equally distribute the context, then all the other well-meaning social, economic, and educational initiatives can’t succeed either.