This partial transcript of the App Fairy podcast has been edited for length and clarity. Visit appfairy.org for more information about Tinybop.

Carissa Christner: Hello and welcome to the App Fairy podcast! Today we’re going to be talking with the makers of Tinybop. These guys make great apps for school-age kids, a slightly older audience than some of the other app makers that I’ve spoken with.

For this episode, we’re going to try something a little bit different. About a year ago I was totally enchanted when I heard an interview with Raul Gutierrez, Founder and CEO of Tinybop by Kabir Seth of the Diversity Sauce podcast, and they were kind enough to let us share part of that interview. Diversity Sauce has some excellent content, and I definitely recommend listening. I’ll also follow up that segment with a mini interview I did with Raul recently.

…

Kabir Seth: [From what I’ve read] your road to Tinybop was a roundabout path. Can you tell me that story?

Raul Gutierrez: I have always been interested in children’s books and kid’s media. The one thing that my parents really spoiled us with was books—we didn’t have a ton of toys, but we had a lot of books. I always loved the weirdness of children’s books, and when I had my own kids, they became my laboratory. We had more children’s books than was really reasonable. I couldn’t wait to expose my kids to all these cool titles.

Once we started to have iPhones and iPads in the house… you know, my kids were really the first generation to see those or play with those as kids. My oldest son was born in 2004 and just when he was becoming cognizant of the world was when the first iPads and iPhones came out. Instantly, they became his favorite toy. He called them “the everything machine” (which is actually now the name of one of our products) because for him they were just that—they were tools, they were toys, they were passive entertainment, they were active entertainment. They did all of these things.

And I realized that I was kind of threatened by the screen, especially in context of kids. I felt that these devices were important and I wanted to understand them. Not so much as a business or anything, but to understand what my kid was doing, why was screen time was so powerful for him, what gave it this draw. What I found, ultimately, was that it’s this incredible form because you’re actually touching something, and then something’s happening back. It’s incredibly responsive.

The more I thought about it, the more I thought about my own childhood. I grew up in a small East Texas town that’s not known for anything good. It’s changed a lot and things have gotten much better, but back then it was really isolated. I thought of it as an island. You didn’t have access to the outside world. But my escape was the library. I would go to the children’s section, and they had sets of children’s encyclopedias that gave you context for the world. I loved the Childcraft library series—they had one book on space, one book on mammals, one book on dinosaurs.

Reading my way through that library, serendipitously, I discovered what I was interested in. I discovered that there was this other world outside of where I was living. What I’ve realized [as an adult now] is that with the iPhone and iPad, Apple and Google have created these amazing distribution systems that can reach everywhere. You can create content that can touch all of those little islands, and the kids who are out there.

The Internet performs largely the same function, connecting people to all these things, but with a horrible interface for a six-year-old. You have to know what you’re looking for, you have to be motivated by the subject. But with a series of apps that’s very, very affordable—and we try to make them even more affordable for schools—a parent can buy the whole series and explain the world. It’s that same serendipitous sensation, not exactly an encyclopedia, but a way to understand various subjects.

I wanted to make them as beautiful as the children’s books that I’d always loved and also just as weird. Because childhood is weird. The way that children see the world is a little strange. There’s so much children’s media that is just extremely straightforward, with the bright colors and the cute characters, which is not necessarily how kids see the world.

From the beginning, we wanted Tinybop to be inclusive, because we wanted to reach these islands of people (and you can be in an island in a big city, just if you come from a bad economic situation, or maybe you don’t have a house full of books). So our question was, how do we, at a very low price, provide a lot of great quality media. Then our next challenge, of course, was to get people to actually download them.

…

KS: You’ve mentioned that your design philosophy is sort of a “design for quiet” as opposed to designing with gamification or badges. Was that a result of research?

RG: I started asking myself, why does screen time bother me so much as a parent? I would see that many so called “kid’s apps” were designed, essentially, to overstimulate kids. They were using gambling algorithms or gaming loops that left kids really jangled. And kids, especially at that age, every parent knows they can be overstimulated. When a kid is overstimulated, they’re often foul tempered and in a bad mood. The minute you take the iPad away, they’re just awful.

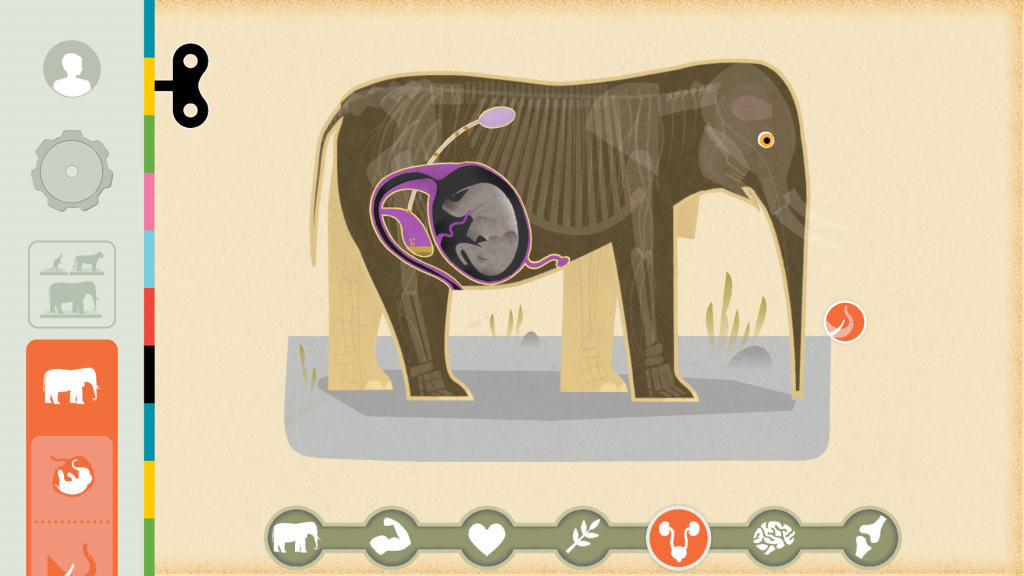

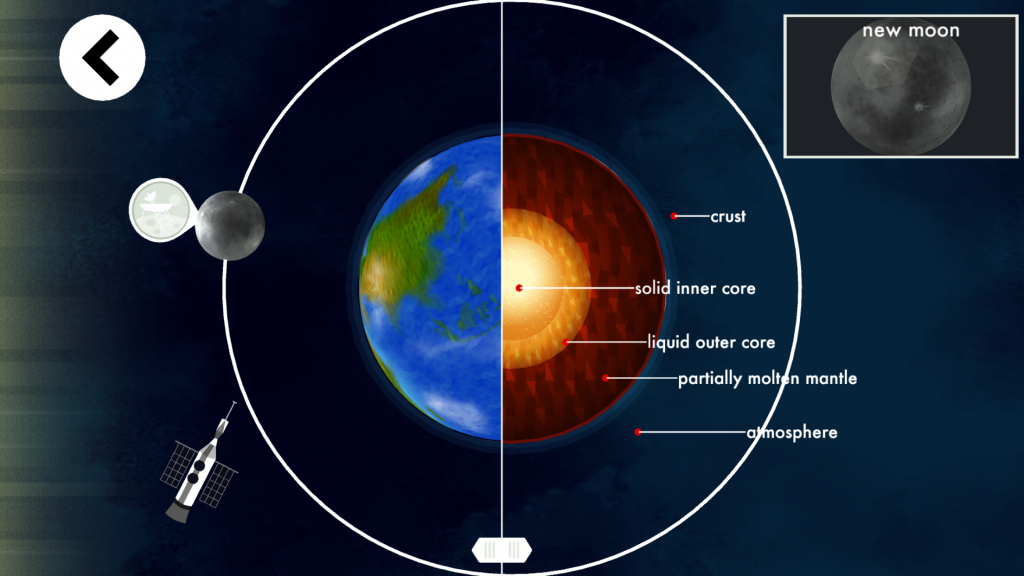

I wanted to do the opposite. I wanted to do what a good book does, what a good science experiment does. We wanted to create “explorable explanations.” So each app in the Explorer’s Library is essentially a working model of the thing we’re trying to show. For example, with the Human Body app, it’s a little model of the human body: you feed it, food goes in one end, and comes out the other. You tap the eye, and we use the camera to show how it works, it blinks. It’s accurate, not dumbed down for kids. There are medical schools that are using the app [with the labels that turn on and off] as a way to help people learn various parts of the body.

The hope is that, in creating this quiet experience, that doesn’t have a soundtrack running behind it and doesn’t have a gamification loop, that you’ll slow kids down long enough that they’ll want to explore. And that’s where the slight touch of weirdness comes in. Because you know, we have to give kids a reason to explore these things. I think that, when we do our job, the output of the apps is not that your kid knows everything about the subject—it’s that your child will ask you questions.

The real goal of that Explorer’s Library series is to start a conversation between parents, teachers, and kids. When we’ve done our job, kids are full of questions. One of my favorite negative comments that we got in the App Store was when somebody gave us a one-star review, saying, “I leave my kid at home with the iPad, and when I come home she’s just full of questions.” And I’m like, this is the point (KS: It’s not a babysitter.) Right. I want you to talk to your kids. That’s really the goal.

…

CC: Wasn’t that a great interview? If you’d like to hear the rest of it, be sure to check out Episode 4 of the Diversity Sauce podcast. For now, I’ve got Raul Gutierrez on the phone with me for a few follow-up questions. Welcome to the App Fairy podcast, Raul!

One of the big questions we focus on is joint media engagement. You mentioned in your interview with Kabir the story of a negative review from someone upset that their child was asking too many questions after using your app—that’s clearly a great way to encourage joint media engagement. Can you talk more about elements of your app designed specifically to encourage connections between people?

RG: From the beginning, our apps have had an inquiry-based philosophy around them. We try to show rather than tell, and we try to embed learning in interactions. Rather than having a page of text, we’ll have the app do something that reveals the meaning.

Oftentimes, the thing that is happening is new to kids, like if they’re looking at something in space or the inside of an elephant. So they will logically and naturally have questions. And we want those questions to come out! We designed a series of handbooks for parents and educators that answer a lot of those questions, and go through the learning goals of the app. For me, that’s the most fun part of the apps. It’s sitting with a kid and asking them what they’re seeing.

CC: You mentioned your handbooks and I want to make sure listeners have found them, because they are amazing. They are probably the best resources for any apps that I’ve seen, offering ways to not just dig deeper into the app, but to also learn more information about the topic at hand. And they’re available in so many different languages too!

…

RG: I think there a lot of people that have a sort of knee jerk reaction to any screen, thinking of them all as equivalent or that anything on a screen is instantly negative. But I look at apps like I do any other medium. There are good books, and there are books that are probably a waste of time. There are apps that are thoughtful and there are others that aren’t. Apps can really add to the way kids see, experience, and understand the world.

Listen to the full podcast.