In January 2018, Michael Levine participated in a panel conversation on young children’s media use hosted by Common Sense Media and the Brooklyn Public Library. Here, in the first of a two-part series, are some of his comments regarding the Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Zero to Eight report.

What does the research say about the effects of technology on kids’ development and learning? And based on this, what stood out to you in the data?

We know quite a bit, going back to the dawn of Sesame Street, on how media and technology affect children’s learning and healthy development. First, we know that too much exposure and inappropriate content—especially for very young children—is not a good thing. Early brain development benefits from consistent, joyful, and rich interactions between a child and caring adults—too much and the wrong kinds of media and technology can get in the way of those exchanges.

Second, we know that all media are not alike—there is a big difference in the impact that educational media and well-designed tech have on children’s learning versus the “empty calories” consumed while watching glorified toy commercials on YouTube, or being desensitized by conflict-ridden offerings. Parking a three-year-old in front of an IPad to play an hour on a poorly designed app is a good deal different from having the child engage in video chats with their grandparents or watching an hour of PBS or Sesame Street programming.

Third, well-designed tech drives active and shared engagement. In the best instances, media can be a tool to prompt rich conversations and to extend the learning beyond the screen, guided by a caring and intentional adult. A useful frame to judge how media and tech affect kids is to consider what Lisa Guernsey and I refer to in our book Tap, Click, Read as the 4 C’s—what is the quality of the content, is the setting or context in which media are being consumed likely to promote human connection, and how do the offerings build the passion or expertise of the individual child. We must also understand how media relate to the cultural and community needs of the child and their family. And the Zero to Eight study suggests that new programming and research is badly needed to attend to cultural and community differences in experiencing media and technology.

Third, well-designed tech drives active and shared engagement. In the best instances, media can be a tool to prompt rich conversations and to extend the learning beyond the screen, guided by a caring and intentional adult. A useful frame to judge how media and tech affect kids is to consider what Lisa Guernsey and I refer to in our book Tap, Click, Read as the 4 C’s—what is the quality of the content, is the setting or context in which media are being consumed likely to promote human connection, and how do the offerings build the passion or expertise of the individual child. We must also understand how media relate to the cultural and community needs of the child and their family. And the Zero to Eight study suggests that new programming and research is badly needed to attend to cultural and community differences in experiencing media and technology.

Two other priorities that the report suggests need attention are 1) an ongoing, more relentless focus on educational equity, and 2) a new public and professional consensus of what constitutes a “balanced digital diet.”

In the Cooney Center’s research, it is clear that inadequate access to media and technology—especially among low-income immigrant families—is a powerful barrier to learning and civic participation. In our recent report, Opportunity for All, we document a participation gap that has been closing in recent years, but is still quite potent. One in four low-income families have mobile-only access to the Internet—which makes it difficult for their kids to succeed in school. Try doing homework or project assignments on a cell phone, or signing up for health care or applying for a job—it’s daunting. The more serious concerns that Hispanic and Latino families voice about the threats to development that media and technology pose is also worth noting. Especially during a time where Hispanic and Latino families are being further marginalized by public policies and practices, we need to make sure that new digital divides do not grow. We cannot allow technology to exacerbate social inequalities instead of opening up new opportunities for everyone to succeed. There’s critical work to do in this regard.

Finally, we need more balance. I’m concerned that parents report that they are reading to their young children less, while watching more videos—which can may be a weak use of mobile access. But I’m also hopeful that mobile adoption has significant promise. The tools available today to young children have the potential to enhance their language, literacy and STEM skills, making them active explorers of everyday phenomenon—from their classroom to their community.

You may have heard that Sesame Street’s Cookie Monster has learned some valuable lessons in delaying his gratification and eating right. His favorite chocolate chip cookie is a “sometimes food,” part of a balanced diet of fruits, veggies and the occasional hubcap. The same needs to become true of children’s media diets. Some experiences that constitute empty calories should be limited, while others that are proven educational like Sesame Street can be more substantive staples. A compelling new book by Anya Kamenetz, The Art of Screen Time: How Your Family Can Balance Digital Media and Real Life, offers wise and practical ideas on how parents and educators can successfully manage the new balancing act.

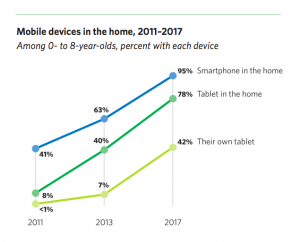

Mobile media has become a nearly universal part of the children’s media landscape, across all levels of society. And a lot of the excitement about the power of technology for learning is focused on apps and games, but we know that video watching is by far the most dominant activity. What are the implications of this? Is all screen time equal?

All screen time is not equal! I am worried about the possible replacement of literacy activities for children under 3 with video watching or poorly designed apps. Our research has documented that the overwhelming majority of apps that label themselves as early literacy drivers are not backed by evidence to support that claim. And there are very few videos that have robust stand-alone literacy value for very young children beyond the ability to label or categorize objects.

What is most interesting is the significant narrowing of the “app gap” as mobile device ownership has become more universal. But as that gap narrows, are we providing parent and professional supports to ensure that vulnerable kids will benefit from greater access? Not yet.

Our research suggests that many parents, particularly those with lower incomes, may not feel confident with technology themselves, nor do they have the mentoring and support to find or use the highest quality content with their children to maximum advantage. And while the report suggests that young children are increasingly facile in operating mobile technologies, we don’t know yet how to best drive educational and home-based practices to extend learning and development beyond the screen. New programs that support trusted media mentors such as librarians and pediatricians and which offer professional development on the effective use of digital media for early educators are now very much needed. A great source of innovative thinking and practical models for supporting media mentors is provided in the pioneering work of Chip Donahue at Erikson Institute’s TEC Center.

Read the second installment of “What Does the Research Say About Tech and Kids’ Learning?”