Last month, researchers AnneMarie McClain and Lacey Hilliard presented some exciting findings from a a study they conducted around classroom media and socio-emotional learning among elementary school students at the International Communication Association Conference in Prague. We invited them to share details of the project as well as the findings that emerged from their investigation.

At the May 2018 International Communication Association Conference in Prague, Czech Republic, we presented some findings from our longitudinal study, the Arthur Interactive Media (AIM) Buddy Project. Together with WGBH-Boston, we developed interactive media and related curriculum designed to foster socio-emotional and character development and to help promote elementary school students’ empathy, tolerance, and prosocial values in school.

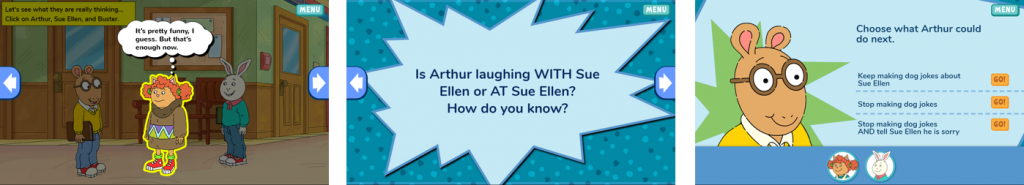

The project included a suite of five digital comics and games based on content from the Arthur© television program, embedded in a curriculum with classroom lessons. The comics, games, and classroom components focus on five main topics: empathy, learning from others, generosity, honesty, and forgiveness. The program was implemented during the 2015-2016 school year in 48 classrooms of racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse students in the Northeastern United States. First graders were paired with fourth graders and second graders were paired with fifth graders to engage in the comics and games, and teachers led classroom sessions during the regular school day. Each comic and game included interactive features, such as built-in reflection questions to prompt discussion about characters’ unspoken mental states and choose-your-own endings that allow children to explore the consequences of characters’ various prosocial and less prosocial actions.

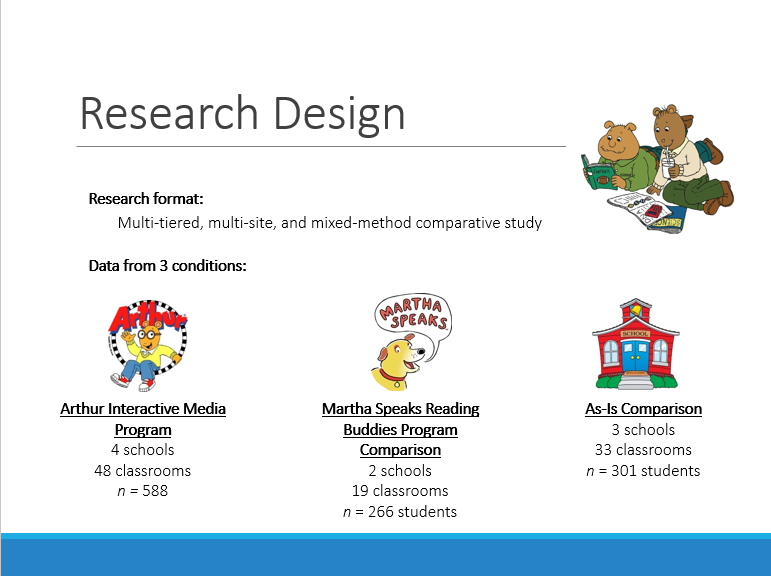

Our evaluation of the AIM program was conducted over the same school year and into the following fall for delayed post-program testing. Data collected included both process and impact data from three waves of student, teacher, and parent surveys; two waves of teacher and student interviews; teacher and student booklets; researcher observations of classroom sessions; and peer buddy video data filmed during students’ conversations while engaging with the comics and games.

Our research design also involved two comparison conditions across 52 classrooms: the Martha Speaks Reading Buddies Program (a cross-age peer buddy program that centered on reading and not on explicit socioemotional and character development content) and an As-Is comparison condition in which schools continued operating with their regularly scheduled curricula.

Results to date are exciting and encouraging.

Program implementation matters

In schools in which teachers implemented the AIM program with high fidelity (e.g., all sessions completed, high quality of implementation, high student engagement), we found a significant increase in students’ self-reported empathy and tolerance levels from pre- to post-test (Wave 1 to Wave 2). Importantly, these patterns were not found for students in the Martha Speaks or the As-Is conditions, or for students in the AIM program in schools that had not implemented the program with high fidelity; these students experienced no significant change on these measures.

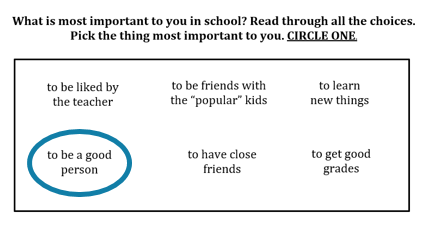

At post-test (Wave 2), students were asked what they value most in school among a set of choices such as “to get good grades,” “to be friends with the ‘popular’ kids,” and “to be a good person.” Students who participated in the AIM program were significantly more likely to report valuing being a good person (23%) than their peers who had not participated in the AIM program (14%).

Long-term effects also showed promise. Six months after the program ended (Wave 3), the significant difference remained: More AIM students (28%) considered being a good person most important to them in school, compared to only 10% of students from the non-AIM conditions. Importantly, no significant differences were found between students by program condition at the pre-test.

We also found other evidence of lasting effects of the program. When it came to comprehension of the AIM target curricular concepts (e.g., empathy, learning from others, generosity) six months after students participated in the program, compared to both groups of control students, AIM students in high fidelity schools were two times as likely to show a better understanding of empathy and generosity, two and a half times more likely to show a better understanding of learning from others and forgiveness, and four times as likely to show a better understanding of honesty.

These results suggest that the AIM program has the potential to move the needle on important competencies, values, and understandings in children, but they also tell us that the content and materials that we created cannot necessarily promote these positive outcomes on their own. How the program was implemented greatly mattered.

The quality of implementation was not only associated with change in children’s empathy and tolerance, as well as differences in their reported values in school and their understanding of target concepts, but it was also linked to students’ perceptions of the quality of their buddy relationships and how excited they were to work with their peers. Students in high fidelity AIM schools were significantly more likely to report more positive perceptions of their buddy interactions throughout the program and more enthusiasm about working with their buddies than students in low fidelity AIM schools—factors that could have absolutely affected student learning, outcomes, and receptivity to the material. It is also important to note that fidelity of implementation was not associated with the socioeconomic status of students. Regardless of whether or not a high fidelity school served children from predominantly lower- or higher-income homes, AIM students in high fidelity schools experienced more positive program benefits in terms of their empathy, tolerance, values in school, and understanding of target topics.

The factors that affected whether or not schools implemented the program with high fidelity deserve additional attention, and they highlight that sometimes, even despite our best efforts to provide resources to support teachers on the ground (e.g., hands-on research staff, real-time responsiveness to teacher requests for support and scheduling changes), not all promising media content will work in every context. Classroom media can be particularly challenging to design because it needs to respond to the demands of unique classrooms, to the specific technological trouble in schools, and it also has to meet individual teachers and students where they are. Therefore, one of our biggest takeaways from this project so far has been that creating innovative, relevant, and developmentally-appropriate content for schools may not be enough—even when that content has been extensively pilot-tested and revised with teachers and students, as our program was before we launched it. It also must be about making versatile content that can adapt to the specific environments in which it is used and designing its implementation in way that affords opportunities to troubleshoot and that helps build support and flexibility into the content and also into each unique partnership. Building on this project to understand how to do that more effectively will be part of our work moving forward.

Power of conversation

High-quality and engaging games and comics were only a component of the larger picture. We also knew that personalized experiences that connect to the game and comics would be important in helping children grapple with challenging and sensitive topics, such as bullying, forgiving others, and tolerance. As such, we designed the comics and games to interlock with peer conversations sparked by the content and also with the larger classroom discussions facilitated by teachers.

Some of our richest data from the study—under current analysis—involve videotaped conversations between buddy pairs as they explore and discuss the comics and games. Our goal was to create content that helps provide practice for real-world situations, as noted by one teacher: “What I’ve used often is to say, ‘Let’s imagine a speech bubble. What do you think this character is thinking? Remember Arthur.’… It’s also helped me when I have a problem that comes up on the playground. I can say, ‘I know you probably don’t remember, but we’re trying to imagine what might you have been thinking. Boys and girls, why do you think this happened? Can you have a speech bubble about that person’s head? What could you possibly think?” Reflecting on the significance of the overall experience, another teacher noted: “I think we had a great relationship with the buddies… one child had said that I feel like now I know how to connect with people.”

We also recognize that important real-world conversations occur outside of school, and that in thinking about promoting children’s tolerance, parents and caregivers play a crucial role. In the parent survey we asked parents how often they talk to their children about moral topics, such as standing up for others when they see someone being treated wrongly. Reports of these conversations significantly predicted a positive change in their children’s self-reported tolerance.

Our findings help build upon the existing knowledge that well-designed, thoughtfully-used, educational, developmentally appropriate media content can help support the development of positive outcomes among children. In response to a question about what one might say when asked about the AIM program, one student responded: “I would tell them that the comics are fun and you learn a lot about how to be a better person. I before didn’t [sic] think as much as I should have about how others would feel. Now I am more aware of that, and I have this program to thank for it.”

As excited as we are by the positive responses and outcomes we have uncovered thus far, our findings also showcase that how media-based classroom programs are implemented can affect who experiences positive effects and to what degree. We are therefore committed to identifying ways to create material that can be flexible enough to more universally promote beneficial outcomes in children. Our analyses also speak to the power of experiences that extend the conversation around the content, as well as conversations that exist outside of the media experiences (e.g., parent-child conversations). Even with the important contributions that the strategic use of high quality media content can make towards improving children’s tolerance, empathy, and prosocial values in school, such content is still only one piece of the greater story of how we can help promote these orientations and values in children.

Access the Arthur Interactive Media buddy Project for free here on PBS LearningMedia

The AIM Buddy Project was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. © 2015 WGBH. Underlying TM/© Marc Brown.

AnneMarie McClain is a doctoral student under the mentorship of Professor Marie-Louise Mares in the Department of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research interests center around understanding how media – and interactions around media – can be designed to better promote positive outcomes for children and families, especially children of color and those from lower-income backgrounds. She is a former elementary school teacher who has taught in Brooklyn, New York and rural Costa Rica and who has developed curricula for preschool and elementary school children in the United States, Costa Rica, and Kenya. She holds a master’s degree in human development and psychology from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, a master’s degree in childhood education from CUNY Hunter, and a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Williams College.

AnneMarie McClain is a doctoral student under the mentorship of Professor Marie-Louise Mares in the Department of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research interests center around understanding how media – and interactions around media – can be designed to better promote positive outcomes for children and families, especially children of color and those from lower-income backgrounds. She is a former elementary school teacher who has taught in Brooklyn, New York and rural Costa Rica and who has developed curricula for preschool and elementary school children in the United States, Costa Rica, and Kenya. She holds a master’s degree in human development and psychology from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, a master’s degree in childhood education from CUNY Hunter, and a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Williams College.

Lacey J. Hilliard, Ph.D. is a Research Assistant Professor at the Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development in the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development at Tufts University. She earned her Ph.D. in developmental psychology from the Pennsylvania State University. Dr. Hilliard’s research takes an applied developmental approach to helping children navigate difficult topics. Specifically, she focuses on how children process and respond to information about social groups (e.g., gender and race) as well as the potential for programs aimed at promoting prosocial development via conversations through media and technology. She was a principal investigator on the AIM study described in this blog and is currently leading the Quandary Project, which is designed to help educators facilitate challenging conversations about ethical decisions through digital game play.

Lacey J. Hilliard, Ph.D. is a Research Assistant Professor at the Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development in the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development at Tufts University. She earned her Ph.D. in developmental psychology from the Pennsylvania State University. Dr. Hilliard’s research takes an applied developmental approach to helping children navigate difficult topics. Specifically, she focuses on how children process and respond to information about social groups (e.g., gender and race) as well as the potential for programs aimed at promoting prosocial development via conversations through media and technology. She was a principal investigator on the AIM study described in this blog and is currently leading the Quandary Project, which is designed to help educators facilitate challenging conversations about ethical decisions through digital game play.