In May, Maayan Eldar and Ashley Mannetta discussed Me: A Kid’s Diary by Tinybop at the International Communication Association Conference in Prague. The app encourages empathy and self-reflection by inviting children to respond to a series of questions about themselves and their lives with drawings, photos, texts, or recordings. We invited them to tell us more how user-testing influences the design of an app, and what the data they have begun to analyze reveals.

Last year, Tinybop launched an app called Me: A Kid’s Diary. Tinybop’s mission is to inspire and nurture children’s curiosity, creativity, and love of learning through playful, interactive, educational products and experiences. In creating our products, we also think a lot about how to teach empathy. We believe it’s an important skill and practice that adults can help children develop from a very young age.

This app was in part inspired by research around social emotional development and empathy—specifically, research that suggests that self-reflection and contemplating others’ internal lives develop empathy. In encouraging children to recognize and label their own emotions and perspectives, we can help them begin to do the same for others. We wanted Me to encourage children to do just that. Our product and research term worked closely together to build an app that would promote children to study themselves, their family, and their friends. The goal was to make these practices engaging for children.

This app was in part inspired by research around social emotional development and empathy—specifically, research that suggests that self-reflection and contemplating others’ internal lives develop empathy. In encouraging children to recognize and label their own emotions and perspectives, we can help them begin to do the same for others. We wanted Me to encourage children to do just that. Our product and research term worked closely together to build an app that would promote children to study themselves, their family, and their friends. The goal was to make these practices engaging for children.

When we began work on Me, we knew that we wanted it to allow children to do two things: create avatars (of themselves, friends, family members, or pets) and answer prompts (about themselves, friends, family members, or pets). But how would those activities be designed? To begin, we needed to consult the children who might use our app.

At Tinybop, we always playtest with children. Through playtesting, we learn what children take away from the interactions, what excites them, what confuses them. With Me, our goal was to engage children in self-reflection—to make questions and prompts that they’d want to answer and that would encourage them to be self-reflective. In all playtesting, we measure engagement to see how we’re doing. With this particular app, we measured engagement as willingness to answer prompts.

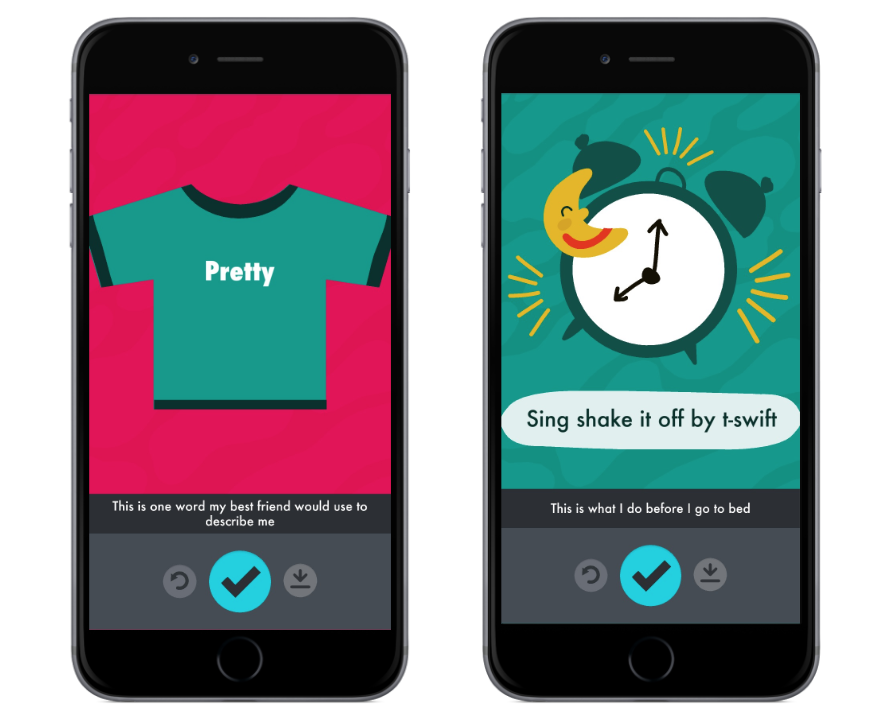

For Me, we wanted children to be able to answer hundreds of prompts to create a “map” of their lives. It was important that these prompts inspire children to think about themselves —their preferences, their habits, and the people in their lives. For example, they might be asked be asked something like, “This is what I do before bed” or “This is one word my best friend would use to describe me”.

To determine what types of prompts were most engaging for children, we conducted a study with 20 participants ranging from ages 7 and 12 from diverse backgrounds. The study was small by necessity. Tinybop spends about six months on each app before its release. As researchers, we work with children to inform our designs and to generate hypotheses to test later, once an app has launched and a larger data set is available.

The children were asked to sort potential prompts into two groups: questions they would answer and those they would not. While children sorted, we asked them to explain in words why they liked or did not like each prompt.

We found that children dismissed prompts that were “too personal”. They didn’t want to answer prompts like “This is what I wish my teacher knew” or “This makes me feel nervous,” possibly because these types of questions reveal something about their private lives. Children were also less interested in answering prompts that solicited generalizations, like “This sums up my life” or “This is my life story.” These more open-ended questions may have been overwhelming to children or may have seemed more difficult to answer.

Children were most interested in answering prompts like “This is what my Dad is afraid of” or “This is my favorite shirt.” This third group of prompts solicited concrete observations. As children said they would like to answer these prompts, we hoped that these prompts would be engaging in our app. That said, since our participant pool was small, we wanted to see if the observations we found held true with a larger audience after launching the app.

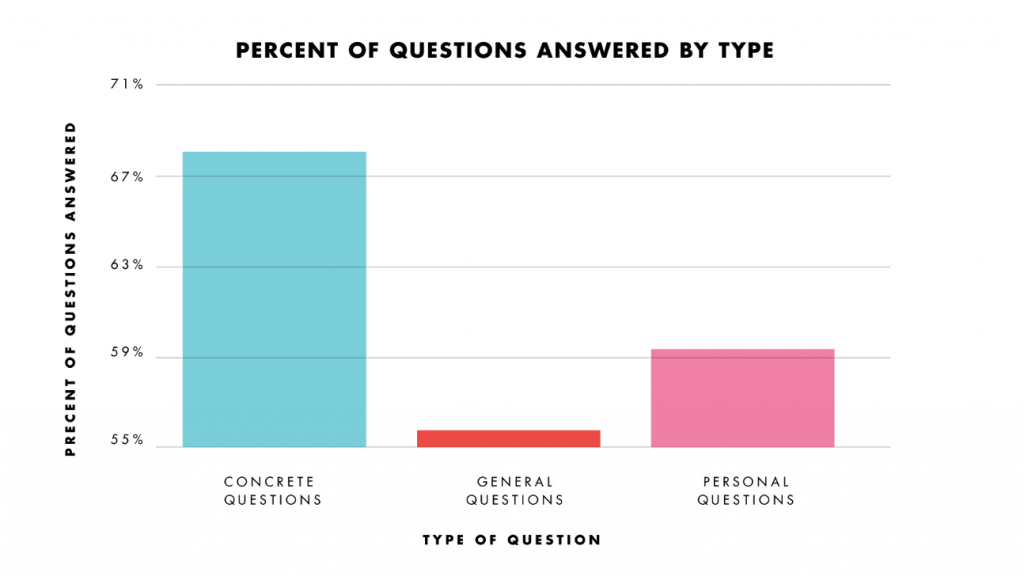

With each of our apps, we collect data to help us improve user experience. As the data from Me poured in, we used it to assess whether the patterns we saw in our play testing among children held at a large scale—specifically, we wanted to see if children were engaging more with prompts that solicited concrete observations and less with prompts that solicited generalizations or overly “personal” responses. We could then use this information to decide which questions to include in future updates to the app.

We gathered data from over 30,000 users from over 140 countries. Engagement was measured by looking at which prompts were answered the most in proportion to the number of times they were opened.

We were excited to find that some of our play-testing observations held true across thousands of users around the world. On average, children answered about 60% of questions they saw in the app. Children answered concrete questions 70% of the time, which was 10% more than average! “General” questions were only answered 56% of the time. Interestingly, “personal” questions were answered about as often as the average. Although children did not explicitly indicate this, they may have been concerned about privacy—that a parent, teacher or friend might read their response.

This analysis gave us important insight into what kinds of questions resonated with children using the app. Specifically, we knew that in future updates to this app, we would want to include more concrete, specific prompts and less general and personal ones. The data does have its limitations and affords room for further exploration. We can’t collect information about age, for example, due to children’s online privacy regulations, and so we were not able to see if children’s behavior changes as they grow.

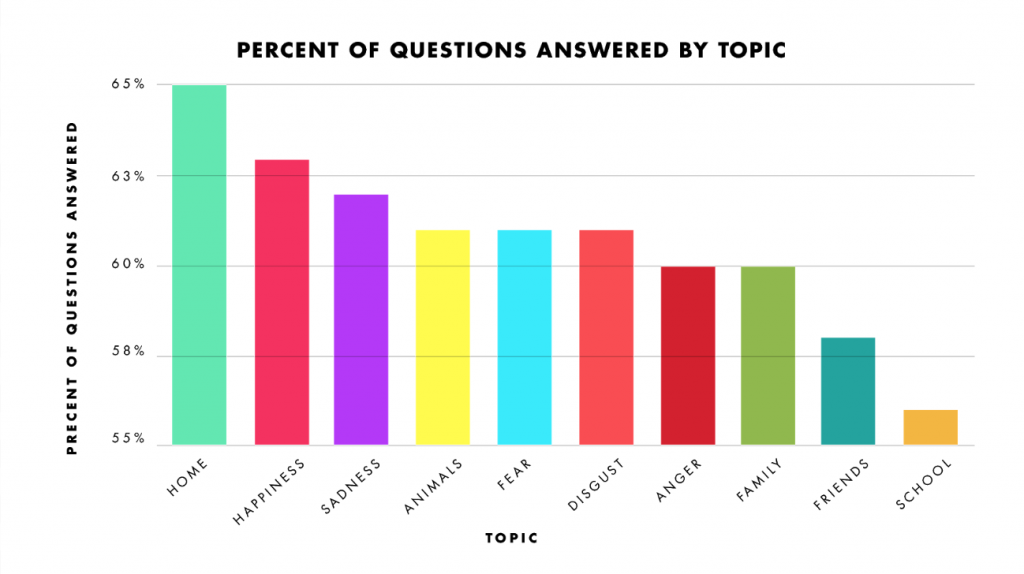

Other trends emerged. We categorize the prompts in Me by topic. There are prompts about family, friends, animals, school, home, happiness, fear, anger, sadness, and disgust. We expected that some categories might be more engaging than others. However, we found that overall children engaged with each topic evenly. There were small variations. Home and happiness proved somewhat more popular than school and friends.

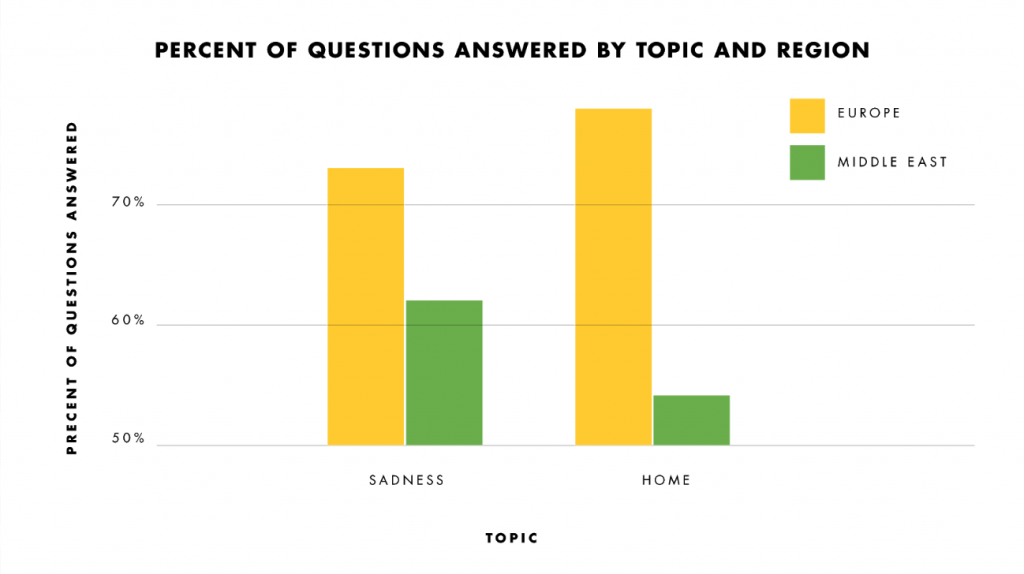

The real variations in the popularity of each topic appeared when we broke children down by region. Engagement with each topic varied according to the location of our users. Users in the Middle East completed more prompts about sadness (62%) than about home (54%), while users in Europe completed more about home (78%) than about sadness (73%). (insert photo #6 around here) These results made us wonder whether cultural and social differences affect the types of prompts that users choose to answer. As our apps are downloaded in countries all over the world, these findings are of particular interest and relevance to us and will be important consider as we develop new apps.

Me: A Kid’s Diary aims to encourage children to think deeply and critically about themselves and their lives through prompts and questions. And while our data does not explicitly indicate that the app itself teaches empathy, we do hope and believe that the conversations and thinking that the app encourages are an important first step towards building critical and fundamental social emotional skills. We hope that our findings might be helpful to researchers thinking about how to engage children in conversations about their emotions and preferences not only onscreen, but offscreen as well.

Maayan Eldar is a Product and UX Research Manager at Tinybop, where she builds products that are friendly, playful, and ready for the world.

Maayan Eldar is a Product and UX Research Manager at Tinybop, where she builds products that are friendly, playful, and ready for the world.

Ashley Mannetta is a user experience researcher and designer at HOMER learning, which designs apps to help children learn and love to read. Previously, she led user research and worked on content development at Tinybop.

Ashley Mannetta is a user experience researcher and designer at HOMER learning, which designs apps to help children learn and love to read. Previously, she led user research and worked on content development at Tinybop.