Creative tools for children should be designed to ensure that learning is playful and engaging. At Scratch, we believe that it is important to use a co-design process, ensuring that the needs and perspectives of our users—especially children—are taken into account at every stage. By involving young people in the design of ScratchJr and Scratch, we can create a platform that truly meets their needs and helps them to develop the skills they need to thrive in the digital age.

Recently, we put this philosophy into practice in collaboration with the Joan Ganz Cooney Center. We set out to understand the barriers to a creative coding experience for the youngest children (K-1), and to have the children participate in designing solutions to best fit their own needs. What we discovered will be immensely helpful as we continue to reimagine ScratchJr, our platform for the youngest Scratchers.

Connecting With Partners

While ScratchJr is ideally introduced to a child by an educator or caregiver, we wanted to explore how to improve the experience of a child in a less-than-ideal situation—where they had little to no explanation of how to get started. The challenge is to include children as young as 4 years old in a fun and playful way that allows them to imagine themselves as the designer of the app and what they’d change.

The Joan Ganz Cooney Center is an independent research and innovation lab within Sesame Workshop that advances positive futures for kids in the digital world. The Scratch Foundation participated as a partner in the Cooney Center Sandbox, a recently launched design and innovation lab that helps digital media innovators create products that are good for kids.

Together with the Cooney Center and The GIANT Room, an NYC-based creative STEAM learning organization, we planned in-person sessions to bring children’s voices into our process of re-imagining the ScratchJr onboarding experience. While ScratchJr has been available since 2014, and is grounded in the pedagogical research of Dr. Marina Bers for developmentally appropriate creative coding, we had not looked explicitly into the onboarding process—particularly for children learning outside the classroom.

Meet Our Co-Designers

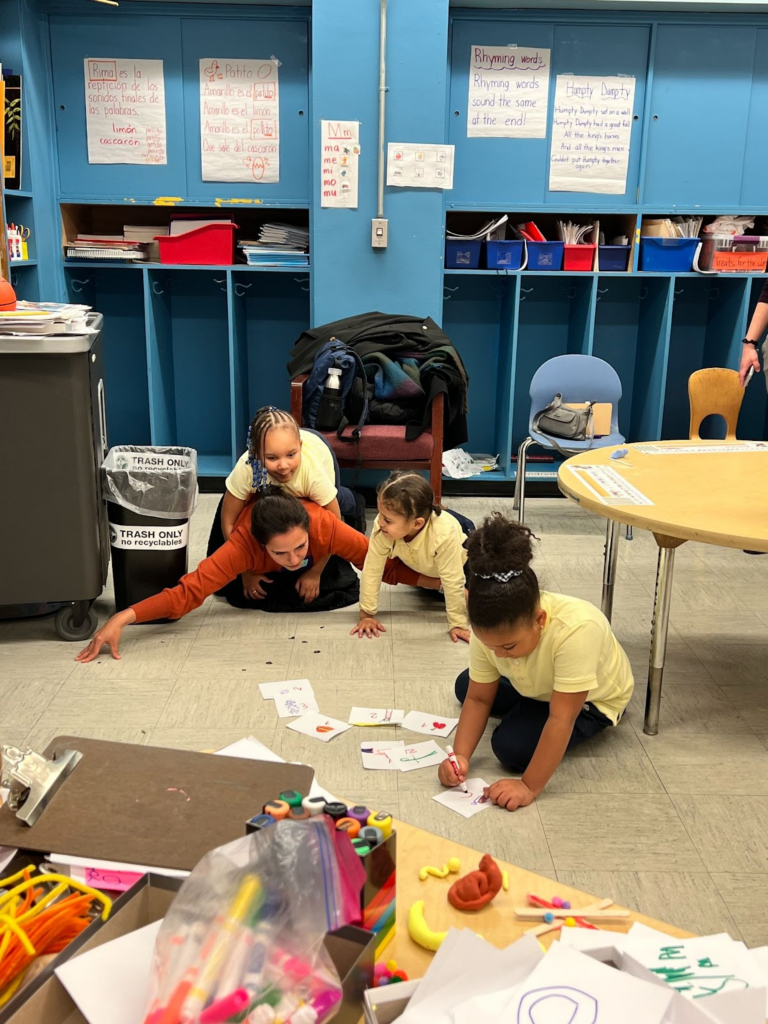

We held the sessions over the course of three days at a public school classroom with fifteen children aged 4 to 6 years old. The school is located in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City, with 94% of its students being eligible for free or reduced lunch. Seventy-six percent of the students are Hispanic, 19% are Black, 2% are white, and the other 2% are Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or have two or more races. Students participated in the sessions through their school’s free after school program, provided by Harlem Dowling.

The goals of the session were twofold: to design and test a framework for playtesting and prototyping sessions that engages the young participants as co-designers, and to gather feedback from the children that can influence our design process for ScratchJr.

We particularly wanted to understand whether children can use ScratchJr independently, learn things for themselves, share with their friends, and teach each other as part of a community. Our hope was to see children helping each other when they got stuck and experiencing manageable levels of frustration that they were able to work through to be successful. We were also interested in observing what they liked and struggled with, and how we could leverage their imagination to discover what we might add to ScratchJr to expand the world of possibilities.

Behind the Scenes: Play Testing

Note: Children’s names have been changed to protect their privacy.

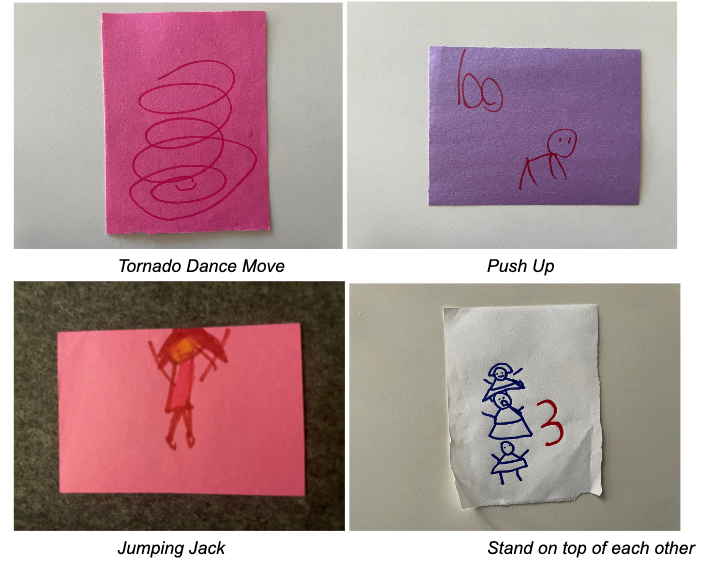

To ease children into the sessions, we began with lightweight warm-up questions—facilitators and kids all shared their favorite games—and unplugged coding activities that sparked kids’ imaginations. When their instructor “became a robot,” children had to speak the “language of code” through crafting materials like pipe cleaners and googly eyes. This exercise helped to prime their computational thinking skills before moving to the ScratchJr app.

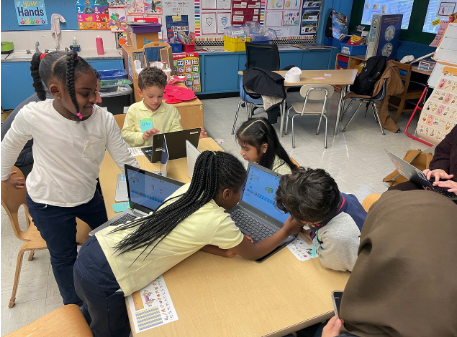

Each student was seated around a common table and given their own device. Minimal instruction was given as the students dove into the paint editor and discovered the coding blocks. Facilitators assisted when students were stuck, but most of the collaboration was organically formed through peer-to-peer interactions and help.

During the playtest, Simone saw that James was able to navigate between the paint editor and the coding workspace easily. She was stuck and asked for his help to “go back,” and he immediately offered to show her how.

We also saw a lot of organic sharing. Stella excitedly showed her friends the “birthday party” she made. When asked if her sprites could sing “Happy Birthday,” she said, “I don’t have that” and was prompted, “Can you make it?” This launched into students discovering the audio record feature, and everyone in the room singing “Happy Birthday” so the audio could be added to Stella’s project.

After students explored the app, they gave their thoughts on the experience with ScratchJr as well as creative coding in general. The feedback was as imaginative and varied as the group of kids we worked with: we heard everything from “add a block so the characters can poop!” to ”add ‘family sprites’ like a family of bears” (which would make story-telling of Goldilocks easier to create) or “sprites that have super powers!”

Digging Into the Findings

After the play-testing sessions, Dr. Azi Jamalian, founder of The Giant Room, and their research team delivered a comprehensive report on findings and recommendations. The ScratchJr team began to process the information and determine next steps to turn these findings into actionable features prioritized in our product roadmap.

How did we do it?

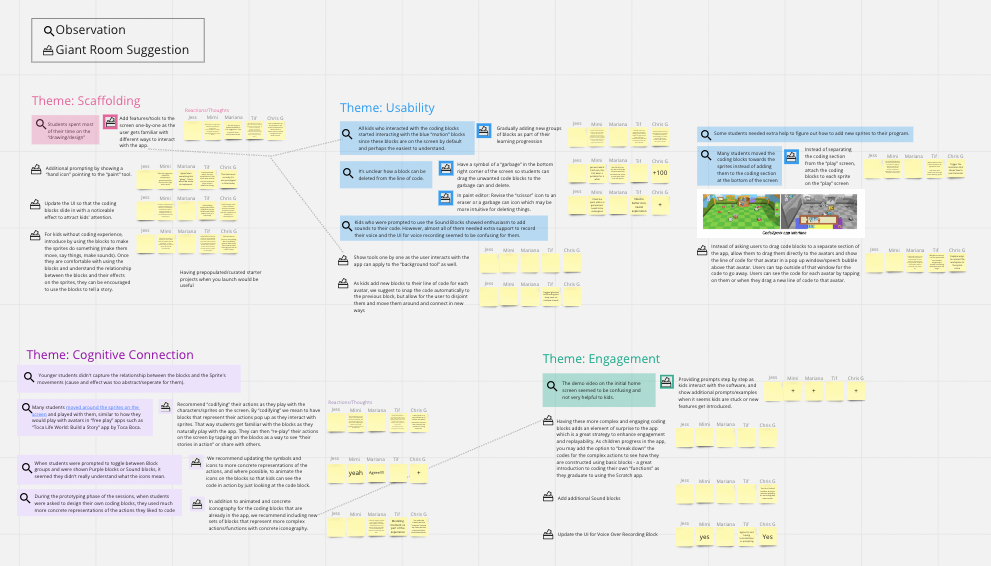

We started by grouping observations and recommended features into four themes: Scaffolding, Usability, Cognitive Connection, and Engagement. The team then discussed each item and gave cross-functional perspectives on what could be explored further or implemented as-recommended.

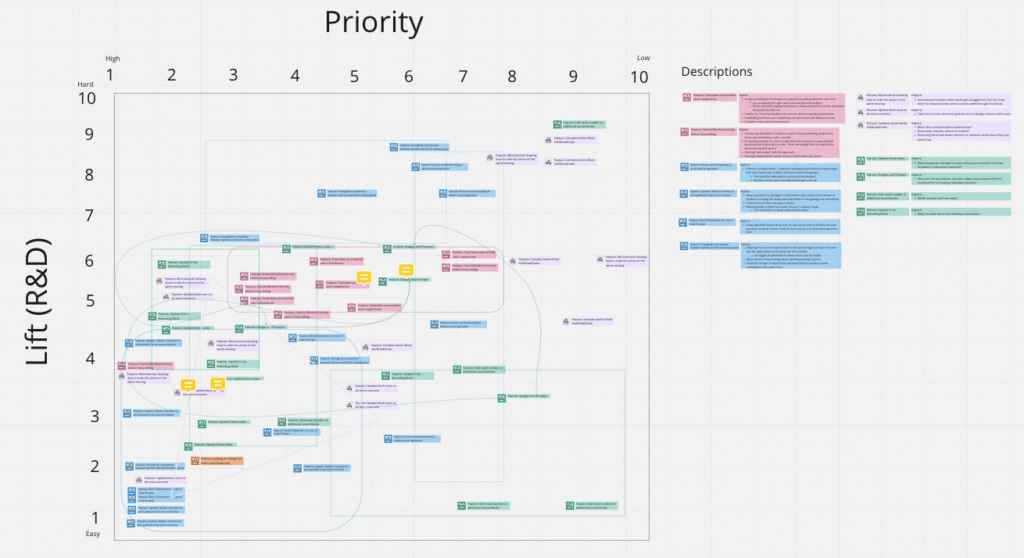

Once the team was aligned on a list of actionable feature sets, individual team members ranked them on two scales: Low-High priority (how important was the feature) and Low-High lift (how much effort would it take to implement the feature).

Suggestions that were determined to be relatively low lift and relatively high priority, like adding a prompting feature showing where to place blocks, were easy to prioritize: we deemed those “Low-Hanging Fruit.” Other suggestions, which individuals ranked at different points on their scales, required further discussion and debate—should we prioritize developing a micro-tutorial for onboarding, given the other explorations around scaffolding that may negate this need?

In the end, we developed a definitive prioritization list. We noted areas of further ideation vs. prototyping, and captured features we plan to explore after the first ScratchJr web release. This documentation was used to inform and add to the existing ScratchJr Product Roadmap.

Co-Design Never Ends

Our time at PS/MS 161M reaffirmed what we’ve always strongly believed: that we can bring the voices of even the youngest users into our design process. After the success of these sessions, we’re focused on more ways to bring co-design into all of our projects, like envisioning the next iteration of the Scratch online community, designing the web version of ScratchJr, or adding new extensions to the Scratch editor.

Scratch and ScratchJr are used by millions of kids worldwide, and as much as we’d love to spend time co-designing in person with each and every one of those young people, it’s not feasible for our team. Through all of our efforts testing in person and online, we’ll continue to prioritize the voices of those who have been excluded from computer science and creative learning opportunities to ensure that Scratch and ScratchJr are more equitable for everyone.

Our team is working to expand playtesting and prototyping for all of our future design efforts. We know that co-design makes Scratch and ScratchJr stronger platforms—and even better, it helps kids feel a sense of ownership in the community they help to build. We’re glad to encourage young people to become active contributors in the technology they engage with, and to help them along the path of becoming lifelong learners.

Learn more about the Cooney Center Sandbox here and sign up for our newsletter for more information. If you’re interested in partnering with us, please complete this form.