When we look to the gold standards of research-practice integration in children’s media established by Sesame Workshop, we know that it is possible for research and practice to be harmoniously integrated to create content that kids and families love (See Joan Ganz Cooney’s The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education, originally produced in 1966 for the Carnegie Corporation).

But how widespread is the desire to integrate research into practice today? Is research equally valued among people who work in public (vs. private) media?

Between March and July 2024, I sought insight into these questions. I conducted a small purposive snowball sample of adults who work, or who have recently worked within the past five years, in the U.S. children’s media industry, including in television, films, gaming, online content, and more. Participants were recruited via my and others’ personal networks via email, LinkedIn, and company slacks (a big thank-you to everyone who helped with recruitment, including Catherine Jhee at the Cooney Center!).

Who was included in the sample?

In total, 65 people completed the survey, and the sample had some diversity. Among those who answered, 56.3% were female, 9.4% were male, 1.6% were genderqueer, and 1.6% were questioning their gender. In terms of ethnicity and race, 1.6% were Arab or Middle Eastern, 4.7% were Asian or Asian American, 4.7% were Black, 9.4% were Hispanic or Latine, 51.6% were white, and 3.1% had other ethnic-racial backgrounds. Overall, 37% held bachelor’s degree, 42.6% held master’s degrees, and 18.5% held doctorates.

The sample also had diversity in terms of years and experiences in the field: 63% had 4 years or less in the industry, and 59.3% reported having worked on content affiliated with public media within the past 5 years. Additionally, though the majority of the sample reported having kids’ television experience (78.1%), other media experience also emerged: 37.5% reported experience with games, 34.4% with kids’ online videos, 32.8% with podcasts, 28.1% with children’s books, 12.5% with movies or films, 6.3% with virtual reality,, 4.7% with AI, 1.6% with music, and 26.6% in other online spaces for kids.

People in this sample also held a variety of roles. I used a check-all box to allow participants to indicate all job titles that applied to their most recent work. Overall, 32.8% of respondents described research as at least part of their role, while 25% indicated curriculum, 18.7% indicated writing (including some head writers), and 18.7% indicated producer or executive producer positions. Additionally, the sample included those with recent experience as assistants, interns, and coordinators (14.2%), creators (12.5%), directors, supervisors, and managers (10.9%), voice over talent and directors (10.9%), executive leadership (e.g., CEOs, VPs or Senior VPs, network executives) (10.9%), and buyers (3.1%).

What did I find?

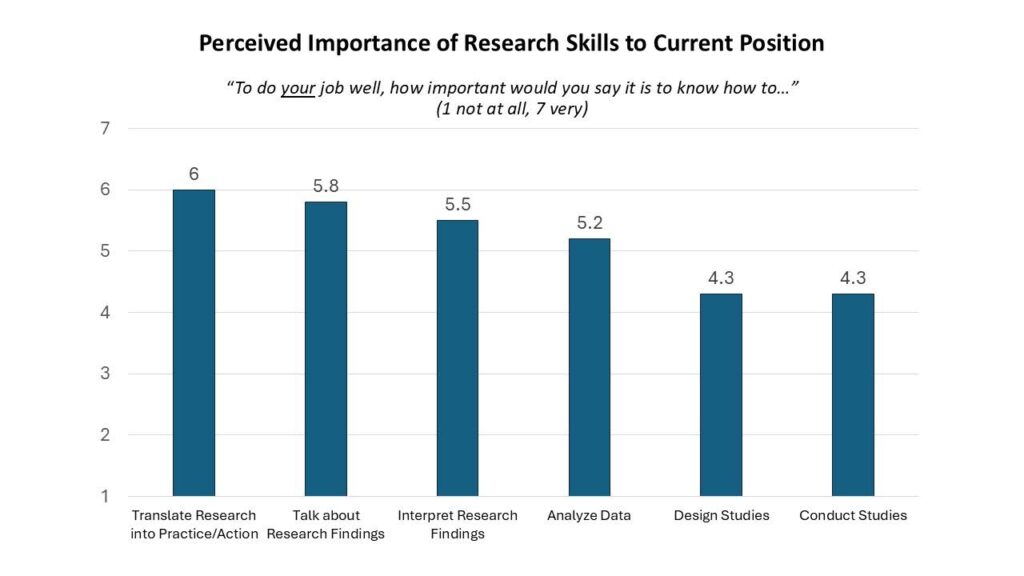

I asked this diverse pool of individuals a series of questions, including how important various research skills were to their work. Specifically, I asked them to rate how important it is for them to be able to interpret findings, translate research to practice or action, analyze data, talk about research findings, design studies, and conduct studies.

The sample reported high levels of valuing multiple research skills. On a 7-point scale, where 7 represented the highest level of perceived importance and 1 represented the lowest level, the specific breakdown of perceived importance is shown in the following chart:

I probed this data further, examining just the ratings of people who work outside of public media and found that the perceived value of these research skills was still strikingly high within the sample. The average ratings of perceived importance for having skills to translate research into practice, to talk about findings, to interpret findings, and to analyze data were all over 5.4 on the 7-point scale.

This all being said, the sample rated expertise around actually designing studies and conducting studies lower than they rated perceptions of the value of having expertise in these other research skills, though even these ratings were above the midpoint.

I also asked people to talk about their hopes for research related to the kind of work that they do. Specifically, I asked them if they could wave a magic wand and have any kind of research implemented to support their work, what that research would be, and what purpose it would serve.

Folks had a lot to say. Some of the most common themes that emerged were about desires for summative evaluation, including longitudinal research, and for formative evaluation.

For example, as one participant explained, they want to know “the effectiveness of the media we are making over time.” Another wrote that they had a desire to know “the impact of media (stories, characters, settings, cultural traditions, type of dialogue used, clothing, and every other detail) on children.”

In terms of formative evaluation, a participant reported the desire to have additional focus group research that allows for a “constant flow of kids’ reactions to content as it goes through the production pipeline.” This idea of having more of an ongoing stream of information is also highlighted in another participant’s comment: “I would love to be able to test stories on real kids before they hit the air, to see if they find the stories engaging and funny. This is something my company does during the development phase for new projects, but does not have the funding to do on a regular basis.”

Participants also underscored the need for research that could help us keep up with evolving technology and today’s children. For example, one participant said: “Research in this area needs to be timely and relevant to the technology and media that is being used and created at the moment (and in the future). Oftentimes, the conflict between academic publishing expectations (e.g., focus on theory) and timelines (forever!) means that the data is too old and too irrelevant of industry to use it in a practical way. From an industry perspective, large scale descriptive data is often very useful especially when it can probe at really specific situations/scenarios, but this is often difficult for academics to financially afford to do (plus that type of data is hard to publish academically).”

There were also multiple comments that reflected the need for more resources for research in industry. For example, one participant said: “I would love to see more shows taking on a full-time research team in order to reap the benefits I’ve seen my production gain from having so much great kid feedback and the child development experts and researchers to back that feedback up.” Another said: “I just wish we were better resourced to complete this work.”

What are some takeaways?

Although the sample in this small study is not representative, and we therefore cannot generalize the findings to all people who work in the U.S. children’s media industry, the findings nevertheless suggest an inspiring point that there may be widespread enthusiasm within the field when it comes to integrating research into children’s media. The findings suggest that current industry professionals with various roles in the industry, across both public and private media, consider it valuable to have research skills and are eager to leverage research to serve youth, their families, and their organizations.

What’s more, participants’ comments about having limited resources for research, and about the misalignment between academia and industry, underscore the point that there is still much more room for us to innovate, collaborate, and combine resources as we look to the future of children’s media.

To me as an academic, these findings highlight the importance of continuing to find ways to focus on the applied implications of our scholarship and of conducting work that is meaningful to those with the power to create content for kids. I am encouraged to continue to build practitioner and community partnerships, and to continue to prepare the next generation of children’s media leaders to excel at integrating research and practice.

AnneMarie McClain, PhD, M.A., Ed.M., M.S. (she/her) is a children’s media scholar at Boston University’s College of Communication. She has a particular focus on understanding how media – and conversations around media – can be used to promote positive outcomes for youth and families, especially marginalized youth and families.