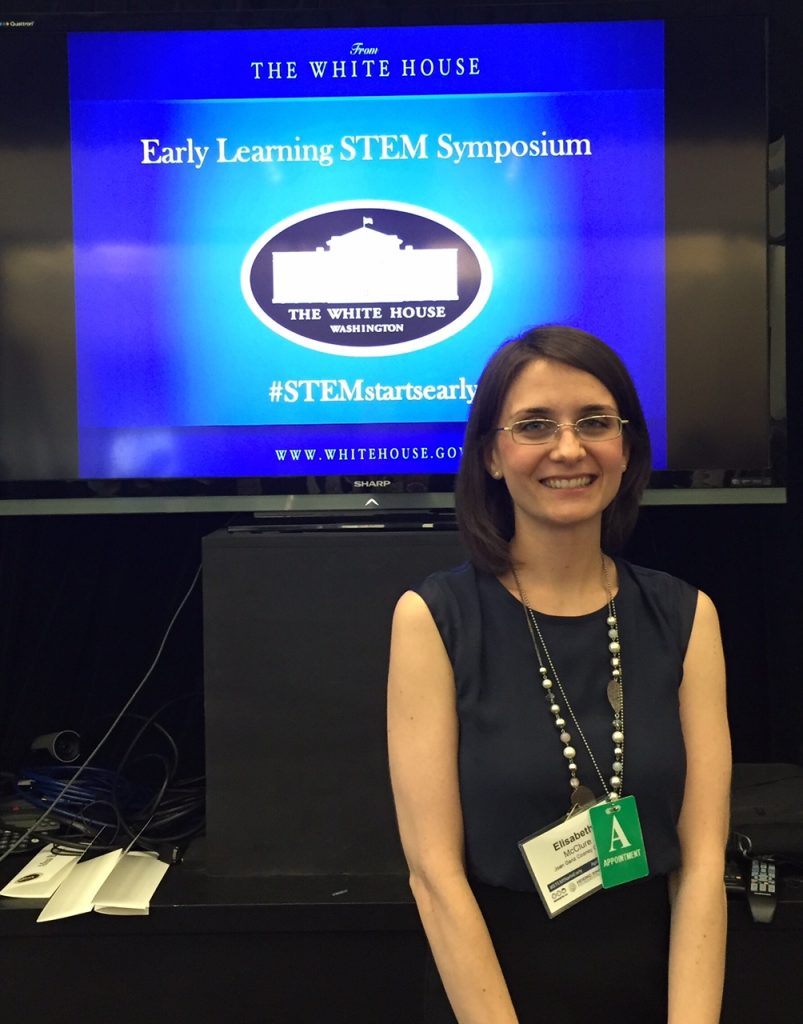

Behind the Scenes at the White House Early STEM Learning Symposium

April 28, 2016

It’s not every day you get an invitation to The White House.

(I’ll admit it: I’m definitely going to put my invitation in an acid-free, archival album for my children and grandchildren to see.)

So it was an absolute honor to be able to attend last week’s Early STEM Learning Symposium at The White House (STEM: Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math). But this experience had particular personal significance for me. I attended graduate school at Georgetown University’s Department of Psychology, a department that trains graduate students to apply their developmental research to public policy issues, and while I was there I developed a complex appreciation for policy. I often speculated, both in and out of the classroom, about how my research could theoretically affect public policy, and as a local resident I often visited the National Mall, the monuments, and of course The White House—but always from the outside of the fence.

Last week I got to pass through the gates (and some remarkable security checks) and go into the Eisenhower Office Building, part of the White House complex. As I stepped into the building, suddenly all my theoretical speculation became reality: for the first time, I was directly part of the policy conversation on early learning. I passed by the Indian Treaty Room, where the Bretton Woods agreements and the United Nations Charter were signed, and into the symposium event space, where Secretary of Education John B. King, Jr., and Roberto Rodriguez, Deputy Assistant to the President for Education, provided opening remarks on the importance of early STEM learning. If you were there, you might have heard some of the following, and truly astonishing, facts:

Did you know that early math skills are a better predictor of high school achievement than early reading skills and that gains in early math skills also transfer to gains in executive function? More and more research is now showing that STEM is actually about developing a way of thinking, not just about specific content knowledge, and that exercising these thinking skills is important for many aspects of learning and development.

Did you know that income-related disparities in STEM (particularly science) abilities are present already in kindergarten? If we want to reduce income inequalities and seed fruitful STEM trajectories for America’s children, we have to start early.

Eminent speakers throughout the day – researchers, funders, and developers – emphasized this repeatedly: Start early. Start early. Start early! I know it probably sounds strange at first: STEM, for most of us adults, conjures up images of our own science and math education, and it probably looked like sitting still at a desk, memorizing facts by rote or following the steps of a chemistry experiment. In fact, as Susan Bales of the Frameworks Institute described in her talk at the White House, many people think STEM is for older kids, particularly for those who display a propensity for STEM, and that it is in direct opposition to playful learning: it’s not for everyone, and certainly not for preschoolers.

But the renowned experts who attended and spoke at the symposium described a different picture. Josh Sparrow, for example, spoke about how children are born scientists: babies, just hours after birth, experiment with cause and effect as they realize that putting their own thumbs in their mouths makes them feel better; toddlers push their sippy cups off the edge of their high chairs over and over and over again to test the limits of gravity; and preschoolers are eager to understand why their clothes no longer fit (life sciences) and are obsessed with the fair distribution of communal snacks (math). The research is clear: very young children are prepared and eager to participate in early STEM activities, and their natural curiosity can be encouraged in developmentally appropriate, playful ways. As The White House tip sheets put it:

But the renowned experts who attended and spoke at the symposium described a different picture. Josh Sparrow, for example, spoke about how children are born scientists: babies, just hours after birth, experiment with cause and effect as they realize that putting their own thumbs in their mouths makes them feel better; toddlers push their sippy cups off the edge of their high chairs over and over and over again to test the limits of gravity; and preschoolers are eager to understand why their clothes no longer fit (life sciences) and are obsessed with the fair distribution of communal snacks (math). The research is clear: very young children are prepared and eager to participate in early STEM activities, and their natural curiosity can be encouraged in developmentally appropriate, playful ways. As The White House tip sheets put it:

For young children, we focus on STEM through exploration, play and building curiosity about the world and the way things work. STEM learning is important for everyone and can happen anytime, anywhere. The real-life skills that people develop when learning STEM help make everyone better problem-solvers and learners.

Yet, persistently, young children—especially those who are low-income, of racial minorities, or are girls—are not getting the rich STEM experiences they need early in life. And, overwhelmingly, teachers are not prepared, equipped, or supported to integrate these experiences into their classrooms.

So what do we do about it? The symposium gave us the information we needed, but now we need an action plan. In addition to the new commitments that were made by the Obama Administration and the remarkable symposium participants, I believe there is a strong need, as Michael Levine said at the event, to take these diverse commitments, these individual rose gardens, and unite them into amber waves of grain. We cannot all act independently—we researchers, policy makers, funding organizations, and teachers—or we risk working past and sometimes even against one another. We need to put our heads together and solve these challenges as one. That’s why the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and New America are convening leaders from each of these areas, many of whom attended the White House symposium last week, in Washington, DC, on May 31 through June 1, to follow up on the meeting and commit to united action. There we will systematically lay out the barriers we face in research, policy, and practice, and collaborate with leading experts to design a national action agenda for early STEM learning.

So, at the end of the day, what did I take away from this White House event (Other than a handful of treasured napkins marked with the Seal of the President of the United States)? I walked away with a deeper drive to help all children gain access to the STEM experiences that will help them grow and succeed in life. Beyond the great personal honor of being able to attend a symposium at The White House, the event confirmed to me what an important issue early STEM learning is and how privileged I am to work on it at such a pivotal time. I’m looking forward to reporting back soon on the action agenda we devise this summer!