Educational media for children should be designed to ensure learning is meaningful and playful. Children should actively engage with content, connect material to what matters to them, and have a joyful and social experience.1 However, research shows that many apps are not designed in ways that support these and other research-based principles.2

One way to ensure that new technologies meet children’s needs is to involve them in the design process. Allison Druin, a leader in the Cooperative Inquiry field and founder of KidsTeam, defines several levels at which children can be part of the technology development process: user, tester, informant, and design partner.3 As users, children are consumers of the technology after it’s widely available. As testers, they try the technology before it’s widely available and provide feedback. As informants, children may have input at various points during the design process and engage in a dialogue with adult developers. Finally, as design partners, children are equal shareholders with adults throughout a design process in which they engage in elaborating on each other’s ideas.

How do these different types of child-centered design play out in practice? The Joan Ganz Cooney Center recently launched the Sandbox, an applied R&D initiative to help digital media innovators center children’s learning, development, and experience in their product design process. Through the Sandbox, we aim to:

- help designers and developers in becoming “kid-literate” by understanding how research and participatory methods can create products that better engage kids

- engage kids from diverse backgrounds to ensure inclusive input into the product ideation process

- build better products that achieve their intended impact and lead to positive outcomes that align with the principles of meaningful and playful learning.

In 2021, we partnered with an early-stage product team to explore ways to mobilize current research and include children in the design process. Entrepreneur Matt Miller had recently begun developing Oko, a new AI-based platform that facilitates small group learning activities, and was a committed partner in this process, which included a series of online co-design sessions with Dr. Jason Yip’s KidsTeam at the University of Washington. One year later, after developing the product further, he returned to bring children’s voices back into the process to further his goals of making Oko engaging, collaborative, and educational.

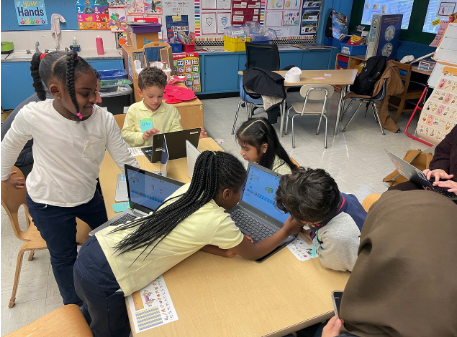

To initiate a new round of child-centered design, the Cooney Center and Oko partnered with the NYC-based creative STEM learning organization The GIANT Room. Together we designed in-person sessions that would meet the needs of all stakeholders by engaging kids as testers and design partners while providing critical ideas and feedback to the product team. We began with a series of sessions that involved children ages 7-12 playtesting the current version of Oko, specifically with a math activity called “crazy calculator”. Playtesting involves conducting user research with children, using a variety of age-appropriate techniques, to help them share their thoughts and learn how to give constructive feedback. In addition to identifying bugs or places where they felt frustrated, we asked them to share their first impressions, how they felt playing the game, and if they would like to play in the future. Kids’ feedback provided opportunities for immediate fixes in the product that resulted in a big impact on their gameplay. For example, Oko’s designers adjusted the pace of the software to allow more time for “thinking” and “brainstorming” among players after one child reported, “I wanted to answer but didn’t get the chance”. They also adjusted the wording of the feedback provided to users to help build math confidence and to encourage them in deeper mathematical thinking.

After playtesting, to encourage more generative thinking, participants were invited to come up with their own ideas for a new game or new features for Oko, make a prototype using a range of everyday arts and crafts materials or creative tools, such as a laser cutter or Scratch, and share their ideas with other participants.

“The GIANT Room is for kids with GIANT dreams who dare to act on them. We know kids have wonderful ideas to share. If given the opportunity, they design the most magical tools, toys, and products that can enlighten millions of other kids around the world,” said Dr. Azi Jamalian, founder of The GIANT Room. “Through our partnership with the Joan Ganz Cooney Center’s Sandbox, we’re giving kids a seat at the table to have an impact on our collective future by directly influencing learning tools that are designed for their generation. Having a voice in designing their own education journey is the first step for them to build the world they would like to live in.”

Children create a math game prototype using a laser cutter at The GIANT Room

These playtesting plus prototyping sessions also yielded ideas for longer-term design decisions and questions, such as how to give kids more agency in controlling the game while also meeting curricular goals. Participating in the sessions allowed product developers to witness spontaneous moments of what kids enjoyed and learned from the game. For example, children learned new math concepts from each other, such as when an older participant answered a question about how to make 56 by entering 56×1 into the calculator; younger participants thought her solution was silly until they learned that when you multiply a number by 1, you get the same number. It also inspired ideas for questions that would be better answered by engaging in deeper design partnership with the children, such as how kids wanted to customize the game and what elements of game design they enjoyed most.

We proceeded to conduct two co-design sessions that were aligned with principles of Cooperative Inquiry, in which children and adults partnered to inform the product design.4 Critically, each small group of children worked with two adults to engage in ideation and co-creation. These adults did not take on the role of educators, but rather were available to listen to and discuss ideas. One of these sessions was designed around a prompt to create a game that encourages collaboration between players. Each small group designed games which they then shared with the wider group, which enabled the developer to consider game elements and characteristics that might be applied in the product, such as working together against a common foe or including scavenger hunts with clues.

Overall, these sessions were incredibly valuable for the Oko team to create a roadmap of child-informed product design goals for immediate, near-term, and long-term implementation.

Oko founder, Matt Miller shared that “Involving children in Oko’s development, through both playtesting and co-design, has helped us to better understand what works – and what doesn’t – for small group engagement, all while ensuring that learning activities remain cognitively challenging. We’ve also found that kids’ unique and unbridled perspectives are often refreshing and surprising – yielding a more creative product roadmap.”

The children involved in the sessions enjoyed creating and collaborating around the design questions; when asked how much their children enjoyed the workshops, parents responded with an average score of 9 out of 10 (N = 19 families), and almost all of the kids wanted to return in the future. In addition to enjoyment, children may also benefit from developing social and cognitive skills such as confidence, collaboration, creativity, and understanding of technology.5

The long-term impact of the design collaboration is an ongoing research question we intend to explore through the Cooney Center Sandbox initiative. This will include developing measures to capture potential benefits for the child and adult designers involved as well as the product itself and whether it better aligns with principles of good design. Expanding access to the design experience for children and communities who may not typically be involved is another key goal.

Learn more about the Cooney Center Sandbox.

References

1Hirsh-Pasek, et al. (2015). Putting education in “educational” apps: Lessons from the science of learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 16(1), 3-34.

Zosh, et al. (2018). Accessing the inaccessible: Redefining play as a spectrum. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1124.

2 Vaala, S., Ly, A., & Levine, M. H. (2015). Getting a Read on the App Stores: A Market Scan and Analysis of Children’s Literacy Apps. Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

3 Druin, A. (2002). The role of children in the design of new technology. Behaviour and Information Technology, 21(1), 1-25.

4 Fails, J. A., Guha, M. L., & Druin, A. (2013). Methods and techniques for involving children in the design of new technology for children. Foundations and Trends in Human–Computer Interaction, 6(2), 85-166.

5 Guha, M. L. (2010). Understanding the social and cognitive experiences of children involved in technology design processes. University of Maryland, College Park.

McNally, B., Mauriello, M. L., Guha, M. L., & Druin, A. (2017, May). Gains from participatory design team membership as perceived by child alumni and their parents. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 5730-5741).