Imagine you were playing a game of Trivial Pursuit and this was your question: What institution has the largest collection of primary sources in the world, a board game on human morality, and now a video game expert?

Answer: The Library of Congress

Trivial Pursuit was just one of the games featured in our August 1, 2016 National STEM Video Game Challenge teacher workshop co-sponsored by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. In the event hosted at the Library of Congress, a group of DC-area teachers explored how to use games, primary sources, and game design structure in their classrooms.

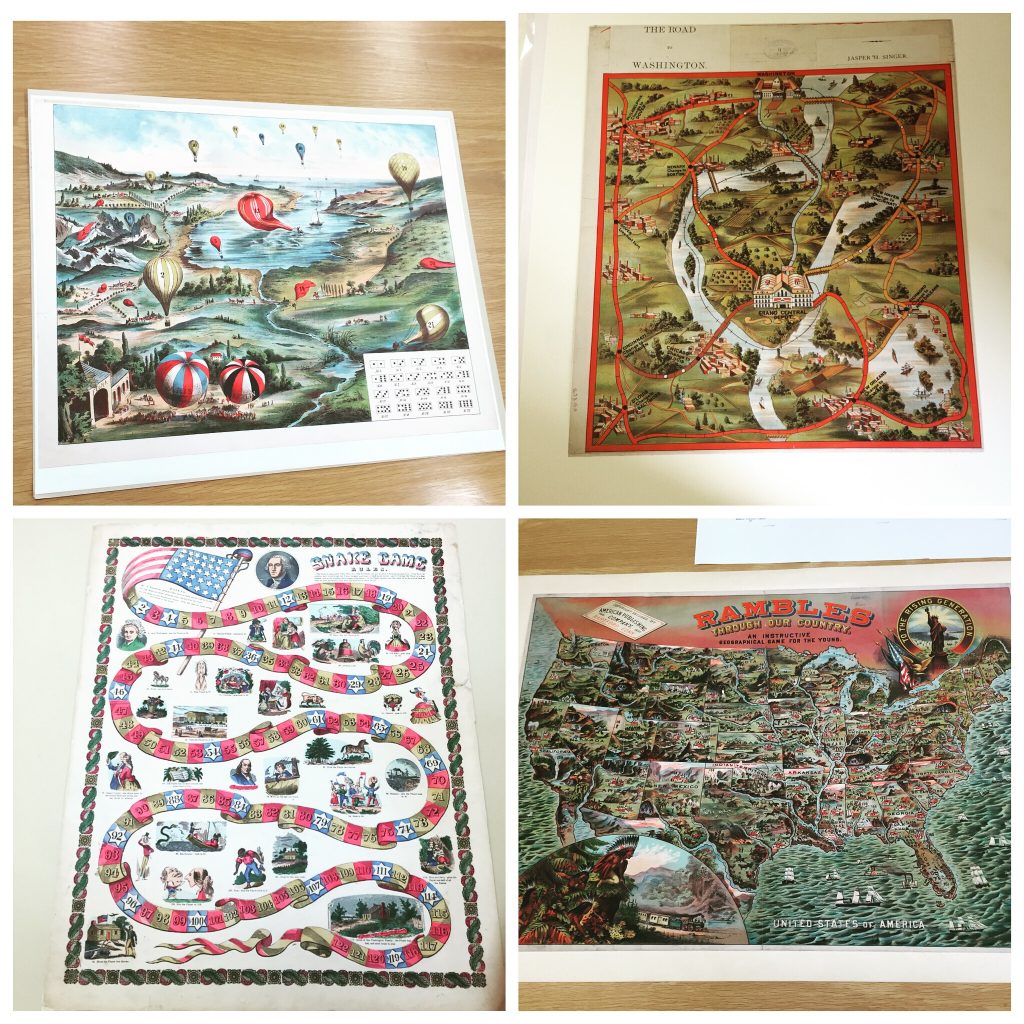

While games and game design education might seem out of place at the Library of Congress, the Library collects games through its Prints and Photographs Division. This division holds over 14 million prints, photographs, and paper media. Additionally, through the Library’s Moving Image collection, they have recently started collecting video games.

Drawing on these resources, workshop attendees had the opportunity to explore six games from the Prints and Photographs collection—ranging from an 1804 French gambling game to a 1988 political game and cartoon in which players race to the White House and citizen spectators are depicted eagerly waiting for the election-cycle dog and pony show to end.

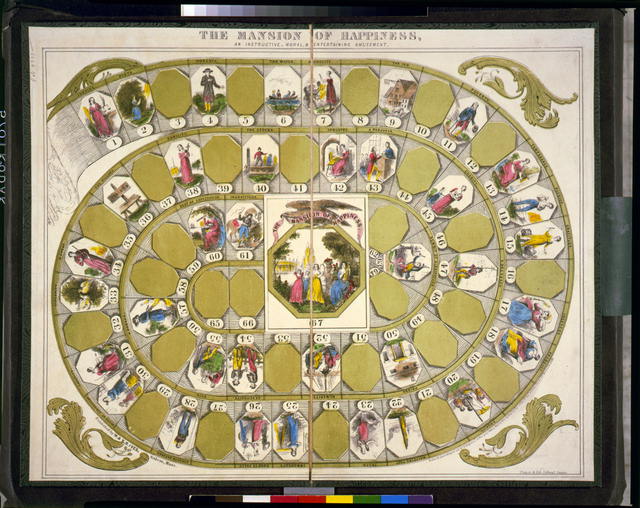

Among the games showcased was an 1848 game called The Mansion of Happiness: An Instructive, Moral & Entertaining Amusement, one of the first commercial games in the United States (although Americans were playing parlor and physical games long before any games were formally being sold). Players race to the aforementioned Mansion of Happiness, avoiding Vices and searching for Virtues. Vices lead to punishments, while Virtues bring game (and moral) rewards. The game rules contain thinly-veiled societal guidelines including:

“Rule 3. Whoever possess PIETY, HONESTY, TEMPERANCE, GRATITUDE, PRUDENCE, TRUTH, CHASTITY, SINCERITY, HUMILITY, INDUSTRY, CHARITY, HUMANITY, or GENEROSITY, is entitled to advance six towards the Mansion of Happiness.

Rule 4. Whoever possesses AUDACITY, CRUELTY, IMMODESTY, or INGRATITUDE, must return to his former situation till his turn comes to spin again, and not even think of Happiness, much less partake of it.”

By playing this game and moving towards The Mansion of Happiness, the game’s designers likely hoped that players would internalize these values, thereby learning the ethics of the time. Through play, rather than memorization, the game taught contemporary students. While educational video games are now viewed as a strong teaching tool, the games explored used visual design and educational theming to get students excited about important content. In effect, The Mansion of Happiness might be one of the earliest examples of an American educational game.

Excited by this source material, the teachers began designing their own games—some educational, some recreational. One group of educators created a superhero-themed game that utilized the classroom to reward different recreational activities—including acting, darts, and design—while another created a board game based on Trivial Pursuit to help students memorize relevant course content. Employing what they had learned about integrating a game’s visual design and goals to motivate educational learning, another group incorporated physical activities to help students internalize physics content. Utilizing balls, cups, and the world around them, the designers hoped to motivate their students to explore their physical space and execute basic experiments. Having taught many STEM workshops over the past few months, I was thrilled to see the attendees utilize the integration between theme and goal to create strong games.

Of course, not all games are or should be educational. When we moved to designing video games, the conversation morphed from games as sources to using sources in our games. For example, one elementary school librarian inspired by her school’s pirate-themed book fair began creating a video game about “Book-aneers.” She used the game’s story to share facts about pirates and her visual design was evocative of a naval environment. By creating both physical and video games, teachers began to see games as teaching tools, as a medium for digital storytelling, and as part of a historic continuum. Most excitingly, by putting teachers in the designer’s seat, the educators saw game creation as an additional curricular tool they could use to encourage and measure learning.

Lee Ann Potter, the Library of Congress’s Director of Educational Outreach and our partner in this joint workshop, encourages educators to use primary sources to help their students develop critical thinking around information and where it comes from. By integrating the Library’s vast digital collection of sources into classroom instruction and digital media design, Lee Ann believes both teachers and students can create games that are not only part of the historic design continuum, but are historic in their own right.