“For me, my kids playing Halo is no different than playing outside and coming up with scenarios that seem kind of violent like our kids… they could be outside playing Nerf guns and pretending to shoot each other and die. I can go outside and play Nerf guns with my kids and we can be playing in the neighborhood. And I don’t get questioned about that, but I get questioned about Halo.” —Abigail, a mother of four daughters

Between the World Health Organization’s classification of video game “addiction” as a mental condition and the blaming of video games for yet another school shooting, it can be difficult to imagine video games as a context for positive learning and connection for youth and families nowadays. But perhaps this is the best time to weigh the negativity surrounding video games in the mainstream media against the growing evidence of their positive cognitive, social, and emotional benefits. Let’s engage in a discussion about the potential of this medium for supporting adults and children in learning about themselves, each other, and the world.

The Families at Play: Connecting and Learning through Video Games book I co-authored with Elisabeth Gee, a fellow researcher at Arizona State University, aims to broaden the public conversation around video games by focusing on the diverse ways video games support family connection, learning, and communication. Written with a broad audience in mind, the book is a collection of five different research and design projects that span a decade. These projects range from interviews with parents and children to observations of families playing popular commercial video games at their homes, as well as games that are intentionally designed to promote intergenerational play across the boundaries of different educational settings (such as home, school, museums, and libraries).

There is something for everyone in our 216-page book. If you are a parent, you will enjoy reading about how other parents are using video games with their children to promote a sense of closeness and togetherness. Just like sharing their favorite music with their children, parents enjoy introducing video games that they played growing up, and later as adults, to their children. Playing video games is one of many mediated activities (both digital and nondigital) that children do around an interest that is personal to them. At the same time, children’s video gaming can be a linchpin in the family system that bonds multiple generations.

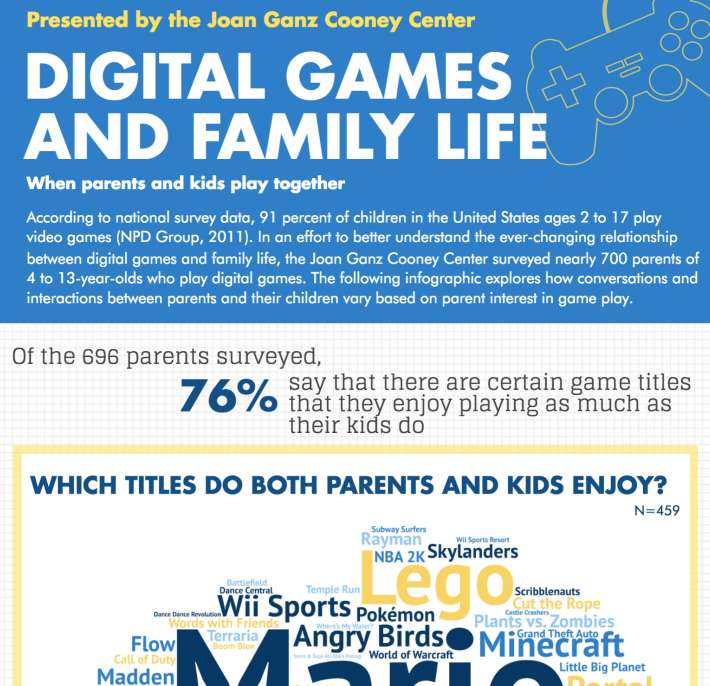

Not all parents who participated in our projects played video games with their children. The national data on family gaming suggests that the percentage of parents who play video games with their children is relatively small. It also falls into gender lines: fathers are more likely to play video games with their children than mothers. That said, throughout the book, you will find examples of mothers from diverse educational, racial, and socio-economic backgrounds playing all kinds of video games with their children for a wide variety of reasons. And while the degree to which families engaged with video games together varied, we observed that video gaming is a family routine and ritual in many households. (For those who are looking to get started, we make suggestions in Chapter 4.)

Our book is also relevant to educators and game designers who play an important role in productively engaging families in learning and connecting through video games. The cases we share and the themes we discuss throughout the book provide insights into the users, namely families, for whom educators and game designers create experiences. In Chapter 6, we specifically discuss the structures and design principles that emerged from our work as being useful in creating opportunities to broaden the participation of parents and children in video gaming. Further, researchers in communication, education, learning sciences, game studies, and human-computer interaction will find the cases that draw on interviews, surveys, and observations of more than 100 families illuminative in understanding families as a whole, as well as their perspectives and engagement with video games.

What motivated us to write this book? Of course, the persistent negativity surrounding video games is one reason. But that’s not all. The debate around “screen time” continues to dominate public discourse and perpetuate parents’ negative perceptions of video games. It often foregrounds ideas such as “unplugging” and “media diet” that implicitly position parents as gatekeepers of their children’s media use rather than participants in their learning around digital media. Further, not all screen time is equal. An hour of watching YouTube, using social media, or playing video games have different affordances for learning and connecting with others. What is most exciting about video games is their ability to immerse different generations in an interactive problem space where players are invited to take on the roles of teachers and learners, collaborating, negotiating differences, and developing shared understandings. Finally, we wanted to challenge the narrow definition of “family-friendly games” and inspire the design of games and game-based experiences that are more inclusive and responsive to the needs of families with diverse backgrounds.

In our book, we draw upon scholarship around parenting, families, learning, and technology to provide a context for findings from our own research and to expand the conversation around video games. We propose that, for children, successful participation in the 21st century starts with intergenerational play experiences at home around technology. Video gaming in particular can be a promising context for parents and children to work as collaborative partners and develop skills that can transfer to other contexts (such as the workplace). We discuss different forms of family engagement with video games that we believe support the formation and cultivation of what Seymour Papert calls “a family learning culture” at home.

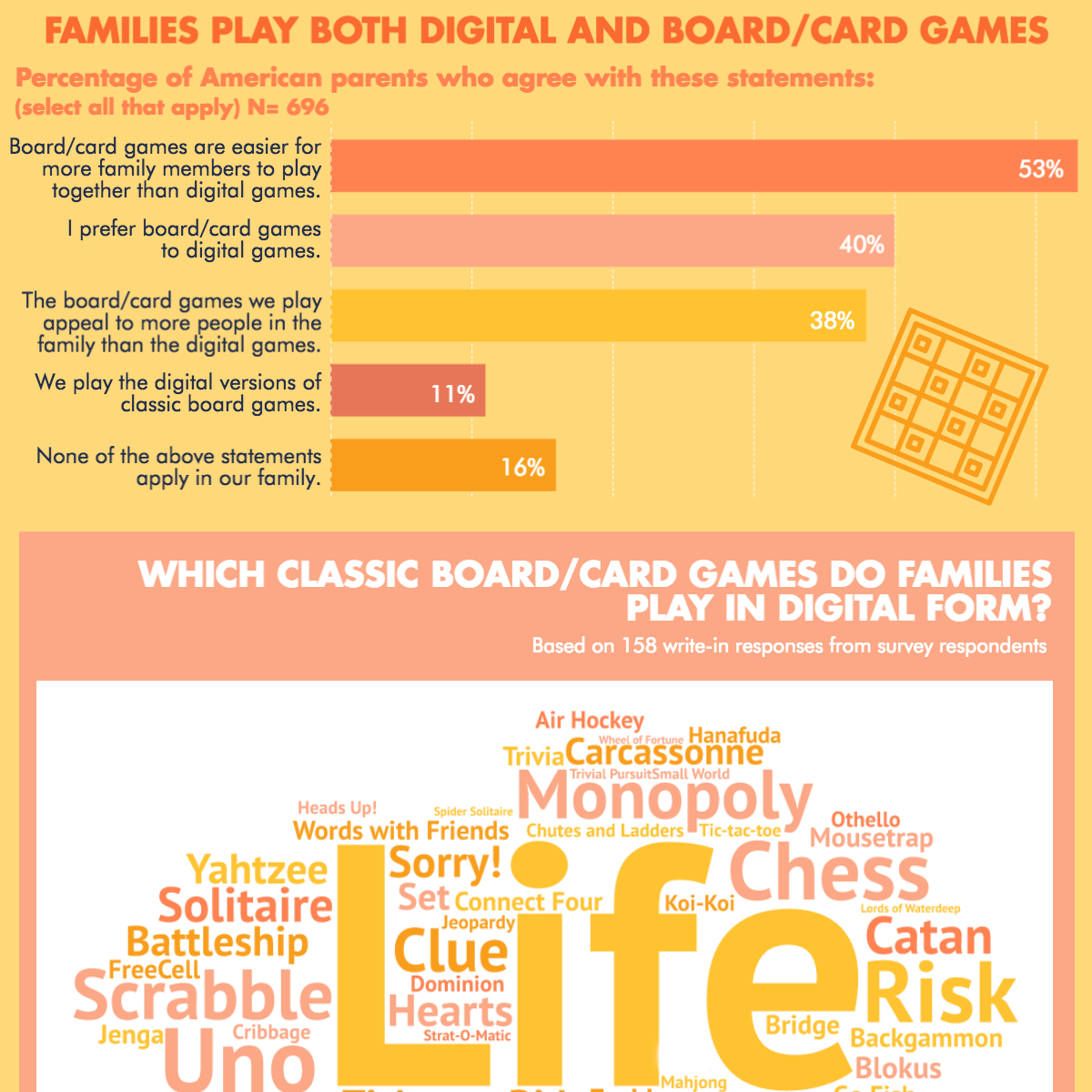

Although families have been playing sports games, board games, and card games together for decades, if not centuries, intergenerational play around video games has been less frequent. It is time to change that.

Sinem Siyahhan, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Educational Technology and Learning Sciences at California State University San Marcos, and the Founding Director of Play2Connect, an initiative that aims to support family learning, communication, and connection through gaming. Throughout the last decade, Sinem has researched and designed educational video games and applications, and game-based learning experiences and programs for youth and families in schools, museums, and libraries. She was a MacArthur Digital Media and Learning Emerging Scholar, and a Science and Technology Fellow for the Gordon Commission on the Future of Assessment in Education. She is the co-author of Families at Play: Connecting and Learning through Video Games.

Sinem Siyahhan, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of Educational Technology and Learning Sciences at California State University San Marcos, and the Founding Director of Play2Connect, an initiative that aims to support family learning, communication, and connection through gaming. Throughout the last decade, Sinem has researched and designed educational video games and applications, and game-based learning experiences and programs for youth and families in schools, museums, and libraries. She was a MacArthur Digital Media and Learning Emerging Scholar, and a Science and Technology Fellow for the Gordon Commission on the Future of Assessment in Education. She is the co-author of Families at Play: Connecting and Learning through Video Games.

Twitter: @sinemsyh