In the last five years, there has been mounting public interest in the relationship between digital technology use and children’s wellbeing. New policies and legislation aimed at promoting children’s rights and/or safety online are being proposed across North America and around the world at an unprecedented rate. Despite their popularity among children of all ages, however, digital games are often left out of the conversation. As is children’s vast knowledge, insights, and willingness to discuss the positives and negatives that digital gaming brings to their lives. Gaming has long been a core digital activity for children worldwide, associated with a range of important benefits and opportunities for children’s play, learning and wellbeing. But it also introduces numerous risks that need to be addressed.

The Child Appropriate Game Design Project aims to fill these gaps by exploring what policymakers, game developers, and children themselves think is “age appropriate” in digital games. We’ve focused on “age appropriateness” because it’s a term found in a lot of the new legislation addressing children and digital technology (e.g., California’s Age Appropriate Design Code Act). But it’s also something that many kids and parents consider when they make decisions about what games to play (content) and how to play them (devices, platforms).

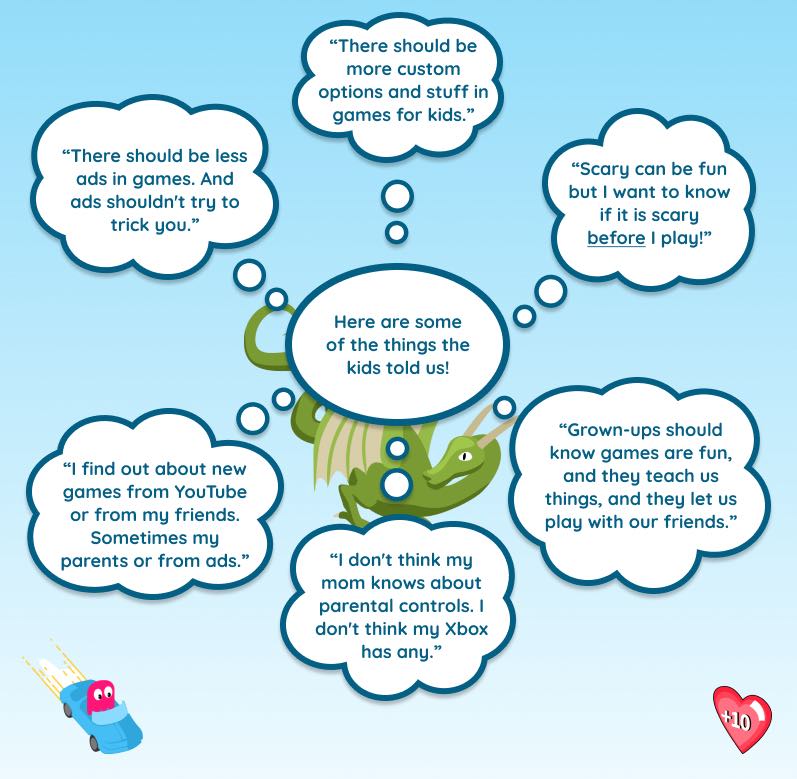

Led by professors Sara Grimes (McGill University), Darshana Jayemanne (Abertay University) and Seth Giddings (University of Southampton), our team has spent the past three years conducting research, including a comparative policy analysis, critical design analysis, interviews, and yearly play-based focus groups with the same 34 kids aged 6-to-12 years. Our analysis of all this data is still underway, but we have some fascinating preliminary findings to share from our first round of focus groups with kids. Here’s a sneak peek of what they told us so far, which you can read in full in our Year One Report.

One size does not fit all when it comes to “age appropriate”

While our child participants did see age as a relevant factor in determining whether (or not) a game is “appropriate,” they said that other factors such as personal preferences and aversions, realism, and maturity are equally or even more important. Some kids said that the presence of “violence” makes a game inappropriate for them. Others told us that the presence of bad words was a sign that a game was inappropriate. Yet other kids said that games with gory graphics or (some) violence could still be appropriate for them and other kids their age who could “handle” those types of things. A common thread across the children’s varied responses was the sense that even kids of the same numeric age could have very different needs, preferences, and definitions of appropriateness.

Many of the kids in our study have trouble finding games they find appropriate for them. Across several focus group discussions (13 to date), it became clear that most of the children wanted more flexibility and customization options in the games they play so that their exposure to content and other players can be better tailored to their individual preferences, concerns, and maturity levels. This is relevant because it suggests that children’s needs are not currently being met by common content management systems like age-based ratings and parental controls.

Some kids like scary things

The idea that “scary” content is a crucial part of the discussion came up in every group we spoke with. The kids often described “scary” and “horror” content as prime examples of the type of “inappropriate” content children might encounter in games. We discovered that some kids like scary games and other kids strongly dislike them, but that most kids fall somewhere in between. In addition to talking about scary games, kids told us about scary in-game ads and their concerns about interacting with scary people in multiplayer games. One thing we heard repeatedly is that kids would like clearer and more detailed content warnings so that they can make informed decisions about which games are right for them. For example, 9-year-old Cat Gamer told us about an experience where they were not properly informed about a game’s frightening storyline: “I was playing a game [that was]…really fun and it was like about this cute little fox, and it had really good animation. But then I got to a section it started getting like really scary. I stopped playing it, but like, it’s kind of deceptive.” Anecdotes like this are common amongst kids and showcase some of the difficulties they face when trying to select which games to play.

This finding is noteworthy because it goes against popular assumptions about the developmental readiness of children at different ages and stages for “grey area” subject matter like spooky themes. At the same time, it supports previous research on children and “dark play” that shows how some scary games and media can have an important or even positive role in children’s lives. Determining what is “too” scary for children is a nuanced endeavour that varies from child to child. Because of this, using age alone as the metric for deciding what is an appropriate level of scary is much more complicated and challenging than it appears. Providing clear and detailed content warnings on games could help kids (and parents) to make more informed choices. This would also align well with the United Nations’ General Comment No. 25 (2021) on children’s rights in relation to the digital environment, which supports children’s agency and encourages giving kids access to important decision-making information.

YouTube is part of kids’ gaming culture

In our focus groups, many of the children told us they get news and information about games from YouTubers. Kids seek information from YouTubers to trouble-shoot in-game issues, to learn new strategies for improving their gameplay, to find out about upcoming games, and to acquire “insider” knowledge (i.e., gaming capital). This confirms previous research on children’s gaming cultures showing that many children use YouTube to develop expertise on games and build social capital. In our own study, 8-year-old Zoey explained the significance of YouTube for social inclusion when she said: “[We] need actually a way of socializing with other people. Because when other people say one thing, you don’t understand it (…) For example, a game. You might want to search it up or something so that if you know that game you can be friends with them.”

This finding is relevant because it shows the continued importance of taking a multi-modal (i.e., transmedia) and holistic approach when trying to understand kids’ digital experiences. If YouTube serves as a key influence that shapes and informs many children’s gaming practices, then it should be included in discussions and studies of children’s gaming cultures. This also means that guidelines and policies related to children’s gaming should be contextualized across digital environments. We need to consider the cross-platformization of children’s play in the development of policies created in their best interests. This is particularly important because children don’t just rely on YouTube to learn how to play games – it also provides vital cultural references that allow them to participate more fully in their peer networks and in the broader information society.

Parental controls are confusing

Parental controls are becoming a staple in the effort to make kids’ digital interactions safer and/or age appropriate. Increasingly, however, parental controls (e.g. content filters, purchase limitations, screen time restrictions, etc.) are configured “behind the scenes” through a separate parent or family account. This can make it easier for parents to access but it also means kids might be getting fewer opportunities to see what parental controls look like or to be involved in decisions about safety and content settings. In our focus groups, the kids had widely varying knowledge and ideas about parental controls. Some kids were confused as to what parental controls did. Others believed their parents didn’t know about parental controls. For example, 9-year-old Fortnite said: “I have parental controls, but my parents don’t know there is parent controls.” Some children weren’t even aware parental controls existed and later in the discussion even suggested that game companies should include some.

We compared the kids’ responses to the answers their parents gave us in the screening survey questions about their use of parental controls. We found that while many parent-child pairs were on the same page about parental controls, many others were not. There were multiple discrepancies and contradictions within parent-child pairs, indicating a lack of communication between some parents and children when it comes to how and why parental controls used. This suggests to us that there is a potential disconnect between parents’ use and assessment of parental controls and children’s understanding of how and why parents are using them (or opting not to). Which can have negative consequences for children’s digital literacy, resiliency, and safety, as seen in previous research showing the vital importance of parent-child communication for reducing exposure to risk online and helping kids develop effective strategies for dealing with risk when it happens. Our study indicates that children need to receive clear communication about parental controls so that they understand their purpose, limitations, and how they fit within family dynamics and household rules.

Conclusion

Children have important insights to share with us about gaming and age-appropriateness, to which many grownups are not privy. This makes it critical that we involve children directly in discussions about age-appropriate design and related policies and incorporate their insights into our work and decisions. The CAGD is helping to fill this gap by connecting children’s insights, developer insights, design analysis and policy analysis to get a big picture of how and why age-appropriateness is being taken up in the gaming ecosystem, and what best practices in this space might look like moving forward. If you are interested in learning more about the project, please check out our website: https://kidsplaytech.com/ where you can read our full Year 1 report and stay up-to-date with our work as we complete our study and share more of our results in the coming months.

Bronwyn Swerdfager (Ontario Institute for Studies in Education), Riley McNair (Faculty of Information), and Alan Bui (Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology) are core members of the Child Appropriate Game Design Project research team and doctoral students at the University of Toronto.