Apps for social communication, learning, and play are a prominent part of nearly every family’s life today. Are they having a similar impact on how families and educators help their children learn to read? And if so, what kinds of apps are they using?

As part of Seeding Reading: Investing in Children’s Literacy in a Digital Age, the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and New America are analyzing the app marketplace to answer these questions. In 2012, we conducted a baseline scan (See Pioneering Literacy In the Digital Wild West). In this post and more to come, we will provide a sneak peek at our updated scan.

Uncharted Routes to Reading

A 2013 national parent survey conducted by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center confirms that the presence of mobile technologies in the homes of young children and families is on the rise. The study found that 71 percent of young children live in a home containing at least one smartphone, and 55 percent of children have access to tablet computers. The same survey indicated that 35 percent of children between the ages of 2 and 10 years use educational apps at least once a week.

With these mobile apps, families now have opportunities to learn anytime and anywhere, whether in the car, on the subway, or waiting for prescriptions at the pharmacy. But most families are left to plot their own route, selecting app resources with very little guidance on the best digital resources for children’s language and literacy learning.

Scanning the landscape of children’s language and literacy apps

While our first report yielded notable insights about the kinds of language- and literacy- focused apps available to families, we realized that the ongoing proliferation of mobile technology and apps since 2012 warranted an updated analysis of the landscape. We wanted to take a deeper look at the kinds of apps available to families with children 8 years old and younger by coding additional aspects of the app descriptions and content.

Our goal was to put ourselves in parents’ shoes. That is, if parents were searching for apps that could help their children learn to read, what would they find? How many such apps are featured prominently on lists in app stores due to their popularity, what skills do they purport to teach, and with which strategies? Are parents likely to encounter the same apps if they looked at expert review sites like Common Sense Media or Children’s Technology Review to guide their choices, or would the language and literacy apps promoted by these experts in the field have different attributes?

We started by collecting the 50 most popular paid and free apps in the education sections of three app stores—iTunes, Google Play, and Amazon apps—over eight weeks in February and March of 2014. From the full list of 1,200 titles identified through this scan process we then identified those apps that were (1) intended for children birth through age 8 years, and (2) focused at least in part on teaching language and literacy skills (based on their descriptions in the app stores. Finally, we obtained lists of highly rated or recognized apps from the Children’s Technology Review, Common Sense Media, and Parents’ Choice Awards. From these three lists, we pulled out 57 additional apps intended for children ages birth through 8 years and targeting language and literacy skills (per their description) to add to our sample, yielding a total sample of 183 apps.

Our coding process includes two phases. In the first phase we are recording numerous aspects of the way each app is presented and described in the app stores, such as the size of the app, the language/literacy skills it claims to teach, and whether it features popular, branded characters. The second phase involves downloading all of the apps in order to directly observe features of the app content, like bi-lingual functions and information provided to parents and educators within the app.

Some early insights

Our coding is currently well underway, and we are excited to have some early insights to share regarding the subset of the most popular paid apps (n = 66). Here are three interesting trends within this subsample and their possible implications.

Finding 1: Language/literacy-focused apps for kids are among the most popular paid educational apps

First, you may be wondering how we arrived at the number 66 for this subset. Here’s what we did: One day a week over an eight-week period, we recorded the titles of the apps that appeared in the top 50 on that day in the educational section of each of the 3 app stores. So that’s 50 paid educational apps x 3 app stores x 8 weeks, which led to a list of 1,200 apps. A lot of those were repeats (apps were often in the top 50 a few weeks in a row). The sample we coded consists of the 66 distinct paid language/literacy apps for kids within the full list of 1,200 apps.

To get a sense of the overall proportion of popular paid apps that are language/literacy focused apps for kids we looked back at the original list of 1,200 apps, with duplicates and all. Of this full list, 447 (37.3%) were intended for children eight years old or younger and claimed to teach one or more language/literacy skills such as alphabet recognition or spelling. Of the 447 language/literacy apps, there were 66 unique titles over the eight-week collection period (that is, 381 of the language/literacy apps were reappearances of those 66 apps in different markets and over different weeks). It is clear that language/literacy apps that become especially popular tend to remain among the most popular educational titles for at least several weeks.

Because our sampling and coding techniques are not identical to those used for the 2012 report we cannot directly compare findings; for example, the Amazon app store was not included in the 2012 analysis. But we can say that from 2012 to 2014, it seems the number of language/literacy paid Google Play1 apps has increased, but decreased for the iTunes paid apps.

Looking within our 2014 sample. Amazon has a higher percentage of apps in the top 50 lists that are for children in our age range and focused on language/literacy skills (43.3 percent), compared to iTunes and Google Play.

Finding 2: Although they are often available across stores, paid language/literacy apps that make it into the list of “top 50 most popular educational apps” in one store are rarely listed in the top 50 of another store.

Our analysis suggests that language/literacy-focused app producers make their apps available through multiple sites, as 79 percent of our sample was available in more than one app store. However, the majority of apps in our paid sample (75 percent) were found among the top 50 most popular educational apps in only one app store over the course of eight weeks. We speculate that app producers prioritize one store over the others when promoting their apps, or that the algorithms for determining the most popular apps vary across stores. Another intriguing possibility is that parents who use different app stores may also end up searching for different items based on how the app store itself is structured. Of note is the fact that apps listed as “most popular” in a store are much more likely to be downloaded by more people than apps that are not featured.2 3 Thus, apps that are already ranked highly may stay in the top spots for much longer and hold onto coveted promotional space that other apps have difficulty obtaining.

Finding 3: Many apps still target basic language/literacy skills, although more advanced skills are notably more common than two years ago

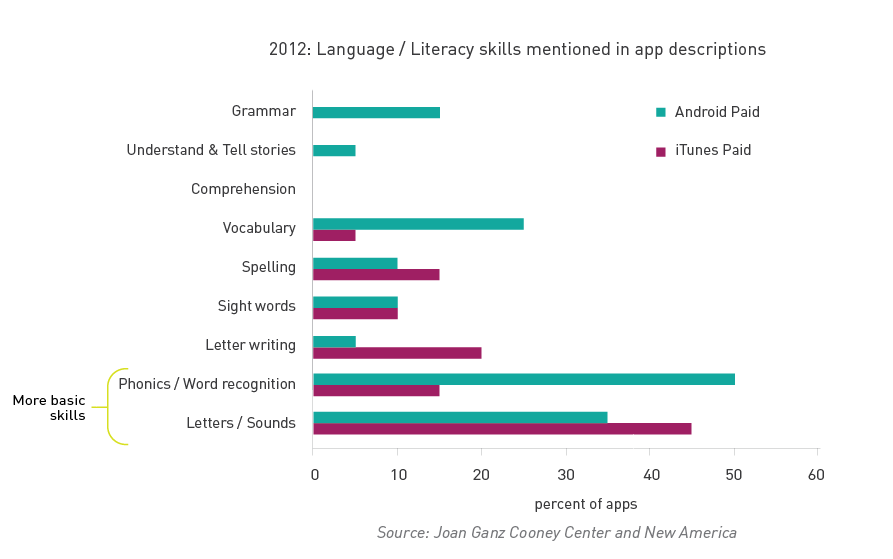

In the case of the particular language and literacy skills mentioned in the app developers’ descriptions, we have begun to document a shifting landscape among the most popular paid apps. Across both time points, basic language/literacy skills, such as alphabet knowledge and phonemic awareness, are commonly targeted by popular paid apps (as described in the app descriptions). However, our analysis reveals a trend towards promoting more advanced literacy skills, as more advanced skills like vocabulary development and reading comprehension are increasingly targeted by popular language/literacy apps for children eight years old and younger. As shown in the charts below, this shift is particularly pronounced within the iTunes store. Though this analysis does not verify or test the content within the apps, it appears that, when taken together, the products in the app store reflect a more comprehensive range of skills that contribute to children’s reading success compared to just a few years ago.

Widening the lens: Stay tuned for more analyses

These are just a few highlights that represent a small portion of our full analysis, which in turn, represents a snapshot of particular features within a limited subset of the full universe of children’s apps. Of note is the fact that many different kinds of apps, even those which do not claim to specifically teach language/literacy skills, may be helpful for children’s reading and language development. Still, even if these findings cannot chart the route for parents and educators, they can at least give us a better sense of the map itself. By compiling and parsing the information that producers divulge about their language-literacy-focused apps, as well as various aspects of the apps’ contents, we hope to provide a clearer picture of the landscape to parents and educators in the driver’s seat of young children’s routes to reading and language development. In coming weeks, we will be sharing additional insights from our paid, free, and top-rated app samples. A book based on Seeding Reading, to be published in 2015, will describe our methodology and complete findings in more detail.

1 At the time of the 2012 data collection this app store was transitioning from the title “Android Market” to it’s current title, “Google Play.” We refer to it as Google Play for clarify and consistency with the 2014 sample.

2 See Garg, R., & Telang, R. (2013). Inferring app demand from publicly available data. MIS Quarterly, 37(4), 1253-1264.

3Shuler, C., Levine, Z., & Ree, J. (2012, January). iLearn II: An analysis of the education category of Apple’s app store. In New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.