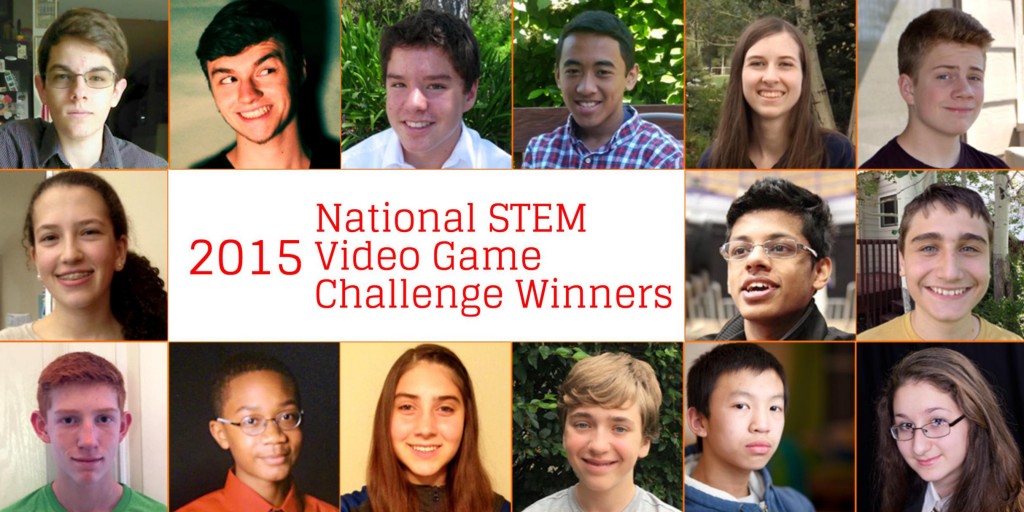

From gravity-defying platform games to science puzzles loaded with informative trivia, the 2015 winners of the National STEM Video Game Challenge never cease to amaze. Learn more about each of the winners and their game designs by exploring their profiles below.

From gravity-defying platform games to science puzzles loaded with informative trivia, the 2015 winners of the National STEM Video Game Challenge never cease to amaze. Learn more about each of the winners and their game designs by exploring their profiles below.

Middle School Winners

- Matthew Bellavia | Gravity Galaxy

- Lance Dugars | The Brink Walker

- Brooklyn Humphrey | Maze Kraze

- Ethan Pang | Science Survivor

- Cole Nutgeren | Pyromania

- John Ripple and John Korhel | The Cube’s Journey

- Sanja Kirova | Ezcape