We are very excited to share new research produced by UNICEF Innocenti – Global Office of Research and Foresight as part of the Responsible Innovation in Technology for Children (RITEC) initiative. The Cooney Center was fortunate to hear insights from the researchers as the report was being finalized.

From a Cooney Center perspective, there are several things that we love about it:

Many initiatives work to create a framework and then leave it there. The RITEC initiative developed the RITEC-8 well-being framework by asking kids what well-being meant to them, but then they took it a step further.

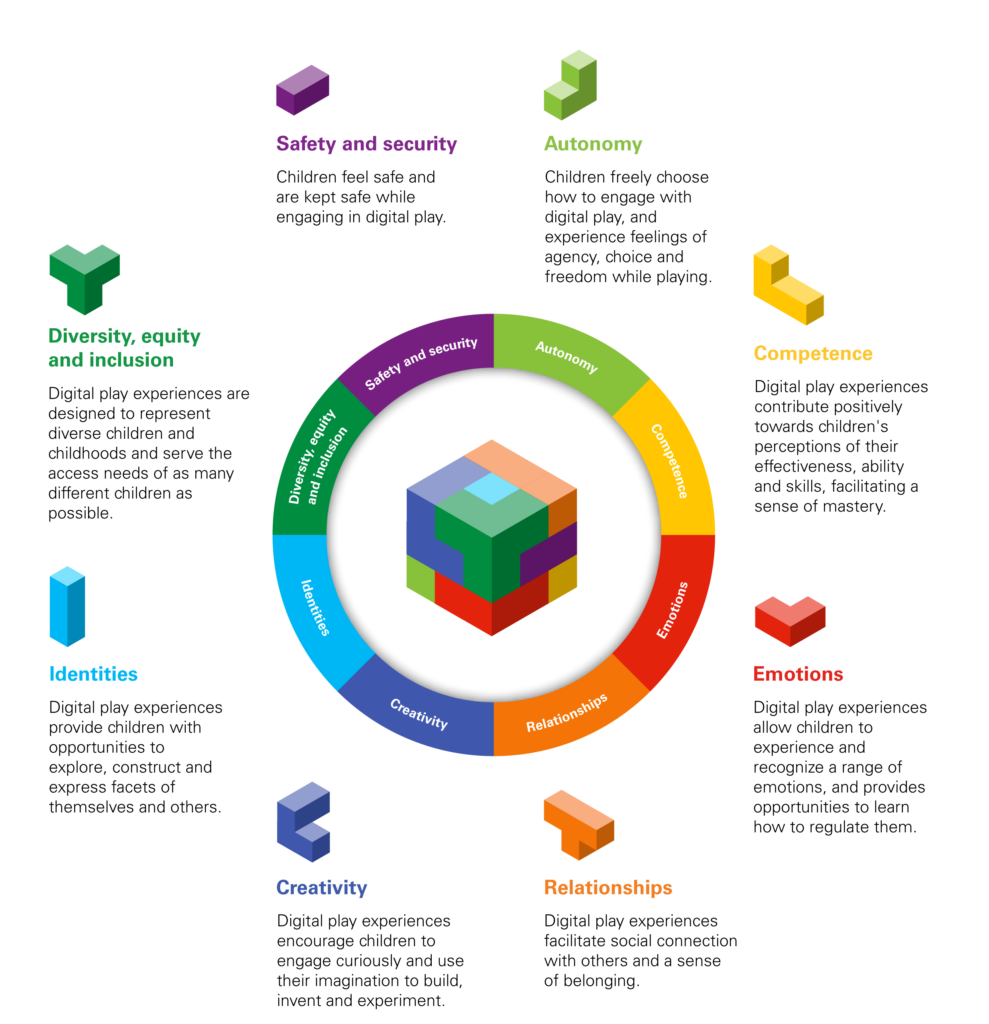

They then asked the question – does this framework hold up when tested with kids actually engaging in digital play? The answer in the research featured in this new report was mostly yes! But the testing results did cause the researchers to make some adjustments to the well-being outcomes: the RITEC-8 have been adjusted to: Autonomy, Competence, Emotions, Identities, Relationships, Creativity, Safety and Security, and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

The publication of this research will be followed later this year by the launch of a guide to assist businesses in incorporating these findings into the games they design, translating research into actual practice.

The research broke out of the usual echo chamber. It was conducted with kids in six countries around the world, including three from the Global South, and involved children with a range of backgrounds, including some children with disabilities. We believe strongly that the more designers can understand the perspective and experiences of all kinds of kids, they will be better able to create digital environments that meet their needs.

This research is thoroughly and carefully child-centered. It met kids where they are, took innovative approaches to getting their perspectives, and allowed kids to disrupt the research plans:

- The biometric research involved showing the kids measurement of their reactions while they were playing games; the children were then asked to explain what they were feeling and why. We love this because it is not simply relying on an adult read of the data. It allows kids to give some extra nuance (and also gets them involved in thinking about their emotional reactions to their reactions while they are playing).

- The ethnographic research allowed for the messiness of life to be incorporated into the research results. No child is playing a digital game in a vacuum. They are impacted by their homelife, they are hopping from a digital experience to homework, to eating dinner, back to digital play after a long day at school where they may have struggled on a test or scored a great goal playing soccer at recess.

- The experimental research was designed for children to play games individually on their own tablets. But the researchers noted that the kids almost immediately gathered together to turn the game play into a community activity – underscoring the importance that social connection plays for children’s well-being. Other kids asked if they had to play online games or whether they could go outside to play instead – suggesting that kids often have a holistic understanding of their own wellbeing and how to balance the on and offline worlds.

We urge you all to read this engaging report – where children’s voices, perspectives and experiences come to life and provide us all with insights that will help us to create better digital play experiences for them.