We talk about kids and AI, and we talk about creativity and AI. But while we know that creativity impacts children’s development, identity formation, and learning, children’s creative experiences with AI are often left out of the conversation. Conversations around AI and kids tend to focus on AI literacy – teaching them the skills they need to understand and use AI in their everyday lives. Certainly these skills are important as AI continues to be integrated into our everyday lives, but my colleagues and I also wondered, can generative AI be used to help kids feel more creative?

| AI Tools Kids Used During Our Study |

| ChatGPT: An AI language model that generates human-like text. |

| DALL-E 2: An AI image generation model that generates different types of visuals from stylized paintings to realistic images. |

| Magenta.js: A set of browser based apps used to generate music. |

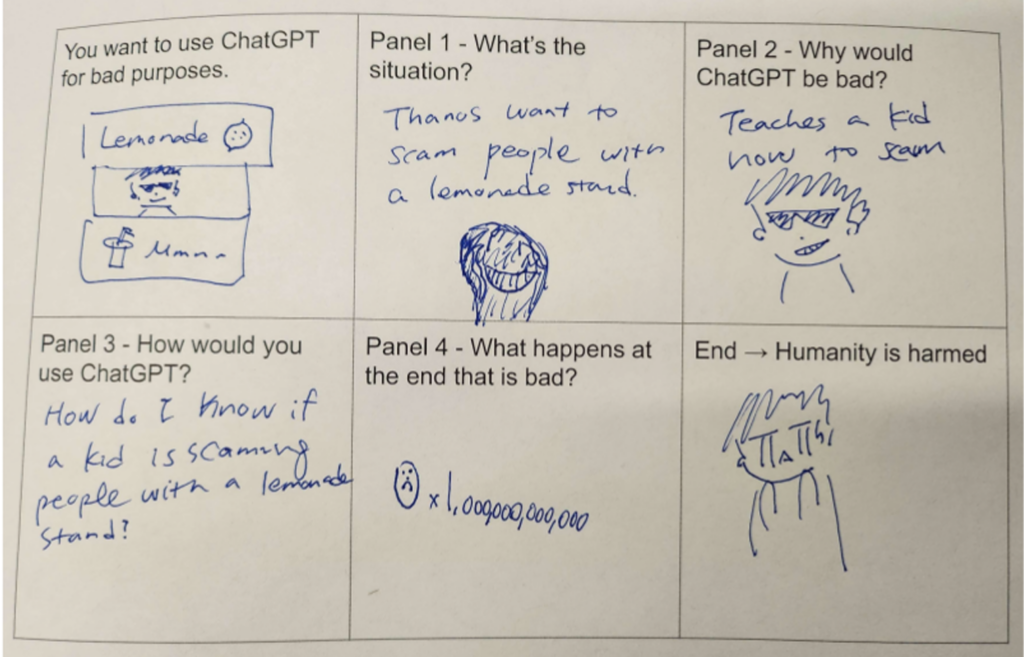

Our co-design group, KidsTeam UW, wanted to better understand children’s perceptions of AI for creative work and the ways that using AI tools could help them think of themselves as creative too. In order to explore this, we asked 12 children (aged 7-13) to engage in a set of six activities within intergenerational co-design teams. In the first three sessions, we used ChatGPT for writing and exploring both “good” uses of AI tools, such as using AI to help stop global warming, and “bad” uses of AI, such as scamming other kids with a lemonade stand. Session four focused on creating images with DALL-E 2, a AI image-generation tool. Session five combined ChatGPT and DALL-E 2 to make storybooks. Finally, we introduced music composition with Google’s Magenta.js tools. During each session, we asked the children to tell us what they liked and disliked about the tools, as well as any ideas they might have to make the tools more helpful to them while creating.

We found that kids didn’t instantly grasp the creative possibilities of AI tools on their own, but with guidance from peers and adults, they were able to create meaningful experiences. We identified four key contexts that can support these experiences:

- Understanding what the system can do. Kids tend to understand AI systems based on their past experiences with other technologies, including other AI systems they may have used before. Because all AI tools are different from one another, children often need help grasping each tool’s capabilities. For example, one child became frustrated when DALL-E couldn’t remember what her character “Lisa” looked like without having to describe her each time. She didn’t realize until an adult explained that unlike ChatGPT, DALL-E doesn’t remember previous prompts.

- Understanding the creative process. Creativity requires flexibility and the willingness to try again. When kids used AI to create, they had to adjust their ideas and find ways to make the tool work for them—like adding extra instructions, rephrasing prompts, or even starting fresh with a new idea. For instance, when they asked ChatGPT to “Write a fictional sports story starting with ‘STEPHEN CURRY SCORES A TOP-RIGHT-CORNER IN THE BOTTOM OF THE NINTH INNING TO WIN THE SUPER BOWL FOR RUSSIA,’” ChatGPT pointed out factual errors. When they rephrased the request as “fanfic,” ChatGPT went ahead and wrote the story.

- Understanding the domain. Generative AI tools often use language that’s too advanced or geared towards adults rather than what kids know and care about. This can make it hard for kids to get their ideas across, especially in areas they’re interested in. For example, when one of the children asked ChatGPT about “dinosaur relationships,” it offered information about herding behavior rather than dinosaur friendships. Plus, children often struggle with knowing domain conventions, making it more difficult to evaluate the AI-generated work.

- Understanding one’s intention and creative environment. Kids, just like adults, have their own opinions about using AI in creative work. For instance, when asked how they would feel if a friend used ChatGPT to write a birthday card, their responses were mixed. Some felt sad and disappointed, thinking AI made the message less genuine and thoughtful. But another child said it was fine as long as ChatGPT was just used as a starting point. Children understand that intention and context of creative acts matter.

Our Tips for Using Generative AI to Support Children’s Creative Self-Efficacy

For us, the most exciting part of our work was seeing children build confidence as they created. Generative AI, unlike other tools, lets children try out ideas in rapid succession, often seeing that their creative ideas are valuable. This allows them to build creative self-efficacy, or the belief that they too can be creative. Self-efficacy can be created in a number of ways, such as seeing their ideas be realized, seeing successful creative uses of AI by peers, and feeling encouraged during their processes. Scaffolding any of the contexts listed above can help to create more meaningful creative interactions for children with AI. Below, we have listed a series of questions based on each context. These questions, when posed to children, can help them reflect on different aspects of the context that align with types of ways to build self-efficacy. In turn, this can help parents and teachers to identify where scaffolding may support children’s experiences. For example, a child who suggests that the AI tool did not give them what they expected to see might be supported by encouraging them to use new prompts, or helping them align their creative choices with what the AI tool can do.

Questions that can help kids build Creative Self-Belief when using AI

- I want to support the child’s relationship with an AI Tool.

- Did the AI give me what I expected to see?

- How easy do I think the AI tool is for me to use based on what I already know?

- How did I get feedback from the AI about why it gave me the response it did?

- How do I feel after using the AI tool?

- How likely is it that I can imagine a positive and successful experience using this tool?

- I want to support the process of working with an AI Tool.

- How much did the answer help me with what I was trying to create?

- How can I see other people doing things well that are like what I am doing?

- How much can I change what I am doing based on the feedback I get?

- How much do I care about the process of making my work with the tool?

- How can I imagine this experience with the tool being part of my overall creative process?

- I want to support the child’s domain understanding with an AI Tool.

- How did what I know help me create what I wanted?

- What are some examples of people using these tools in my area of interests?

- How much does what I made follow the usual rules for this kind of work (i.e., a story, song, or drawing)?

- How do I feel about working with this area or topic?

- How can I imagine using this tool in my specific area of work or interest?

- I want to support a child creative expression with an AI Tool.

- How well did the AI help me to finish what I wanted to make?

- Can I find examples of people using the tool well for what I want to do?

- How did the feedback help me with what I wanted to create?

- How can I keep myself motivated while working on my creation?

- How can I picture this tool helping me achieve my creative goal?

While these questions can offer both feedback and suggestions on how to scaffold certain contexts, here are a few extra tips for helping the kids in your life build their creative self-efficacy using Generative AI:

- Help children see themselves as creators. Encourage children to see themselves not only as students but as creators, capable of making art, stories, and music. Children have things they want to say and share, just like adults. Empowering children encourages them to see value in their own ideas and the process of trying to create, rather than only the product of creating.

- Guide creative adjustments. Offer guidance on how children can refine their ideas when using AI tools. Help them decide when they want to try something new, or stick to their original creative idea. This might look like suggesting a new approach when using a tool or giving them more ideas to work with. Note that supporting any context will help the others. For example, helping children learn more about a creative domain will in turn help them understand the potential of a system, new possible adjustments to their process, and help them define their intentions.

- Foster ethical conversations around AI in creative work. Don’t shy away from helping children explore the role of AI in issues of authorship, originality, responsible use, and authenticity. We suggest that offering children the chance to express themselves with AI can provide meaningful opportunities to discuss broader questions of ethics and the role of technology in their lives and identities.

- Frame AI as a creative tool. Encourage children to see AI as something that can support their creativity, while also building their own skills of self-expression. Remind them that AI is only one tool to help creatively express themselves, there are lots of other tools they can use from other computer programs to pen and paper! AI is not a replacement for creating, but simply another way they can create. They must still learn about their own preferences, domain conventions, and consider how they most want to share their unique experiences with the world.

Check out our paper about AI and Creative Self Efficacy here.

Newman, M., Sun, K., Gasperina, I.D., Pedraja, M., Kanchi, R., Song, M.B., Li, R., Lee, J.H., & Yip, J.C. (2024). “I want it to talk like Darth Vader”: Helping children construct creative self-efficacy with generative AI. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-18).

Michele Newman is a doctoral student in the Information School at the University of Washington advised by Dr. Jin Ha Lee. She is also a member of the UW Gamer Group and the Digital Youth Lab working with KidsTeam UW under Dr. Jason Yip. Her research broadly explores how the design and use of software can support creativity and aid in the creation, transmission, and preservation of cultural heritage.